Africa’s New Oil and Gas Producers Must Prepare for More Disappointment in the Post-Coronavirus Era

This article was first published under a different headline by The Africa Report. Update: The World Bank working paper from which this analysis was drawn has since been published.

The crash in oil and gas prices, triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and the slump in economic activity, has dealt a blow to the plans and public finances of major oil- and gas-producing countries. But a group of countries in sub-Saharan Africa once designated as “prospective producers” are facing a different challenge.

For new producers in the pandemic era, some licensing rounds are likely to be cancelled, and production is being pushed back once more. Debt is becoming an even greater issue. Yet some investors—like Total in Uganda—still show signs of interest.

To clarify this mixed picture, we have reviewed our analysis of the experience of the 12 sub-Saharan African countries that made their first major discoveries during the period from 2001 to 2014.

Despite significant excitement from governments, companies and a range of international organisations, each country reality has fallen short of expectations. Many hoped that these oil and gas discoveries would propel development.

However, the sector has yet to deliver any benefits for many of these countries and has delivered less than the expected benefits for others. We studied the series of disappointments these countries faced, the timeline for getting to first oil or gas and revenues.

The sector has always been inherently unpredictable, but these disappointments highlight the dangers of the “presource curse”—the economic risks a country faces from discoveries before the first drop of oil or molecule of gas is produced. The current coronavirus-related market turmoil is likely to further accentuate this trend. Here we discuss some of the key findings of our analysis and place them in the current context.

Disappointing discoveries, delays and dollar amounts

In four of the countries we reviewed—Guinea Bissau, Liberia, São Tomé and Principe and Sierra Leone—companies ultimately deemed their discoveries commercially unviable.

These countries continue to organise licensing rounds in an attempt to rekindle interest in acreage that had failed to deliver on its early promise. But with the global crash in oil prices and associated reductions in exploration investment, it is likely that several governments, including Liberia’s, will cancel their licensing rounds this year.

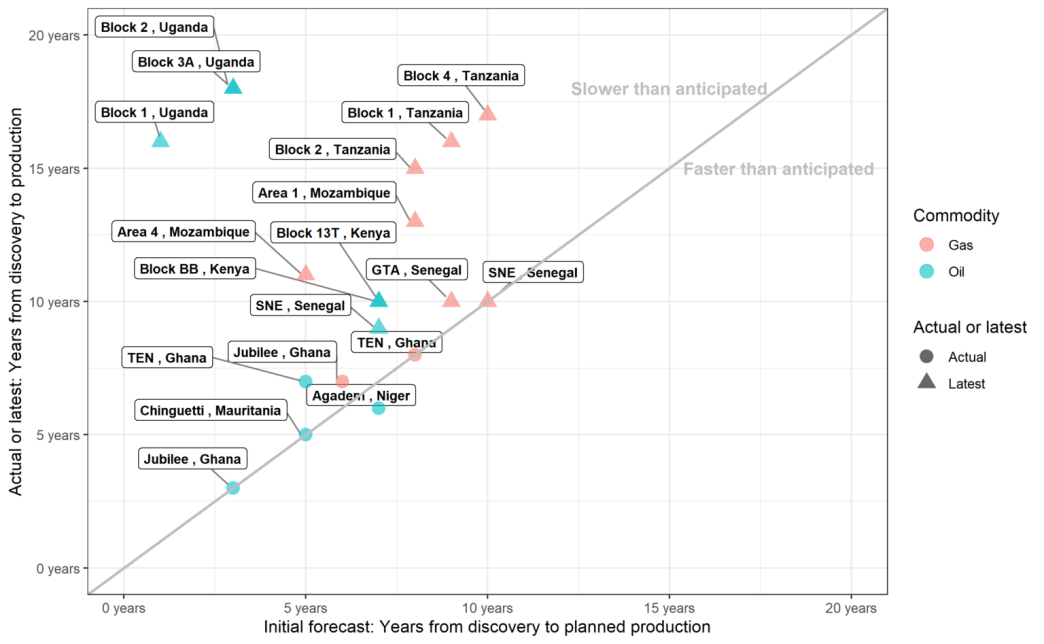

Among the eight countries with potentially commercial discoveries, most are yet to reach production. As of January 2020, timelines were an average of 73 percent longer than initially forecast.

Initial forecast versus actual or latest timeline from discovery to production (as of January 2020)

Uganda, for example, was initially predicted to start oil production in 2009. However, early and excessive optimism on the timeline was compounded by protracted negotiations on taxes, how much oil should go to a domestic refinery and the route for an export pipeline.

Total’s recent purchase of Tullow’s stake in the Lake Albert project suggests continued investor confidence in its viability.

But the current turmoil is likely to further delay a final investment decision (FID) and first oil; the project’s relatively high break-even price could endanger it if prices don’t significantly rebound.

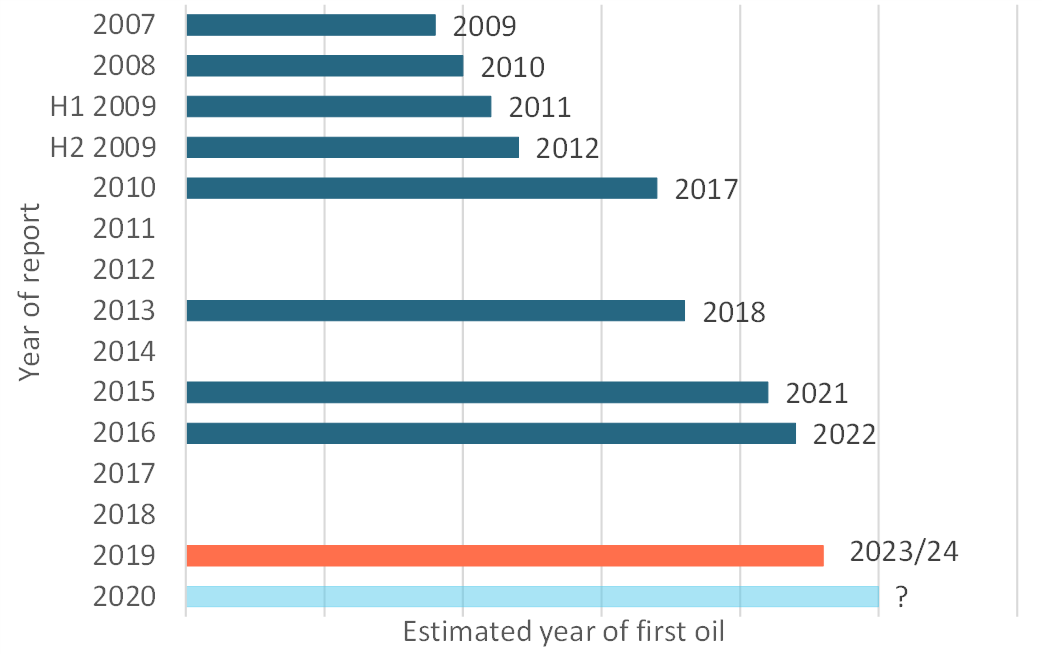

Changing first oil estimates for Uganda in International Monetary Fund reports

In April, Kosmos announced a one year delay in production at the Senegalese-Mauritanian Greater Tortue Ahmeyim liquefied natural gas project, while financing doubts have arisen for Senegal’s first oil project. More announcements of project delays are expected.

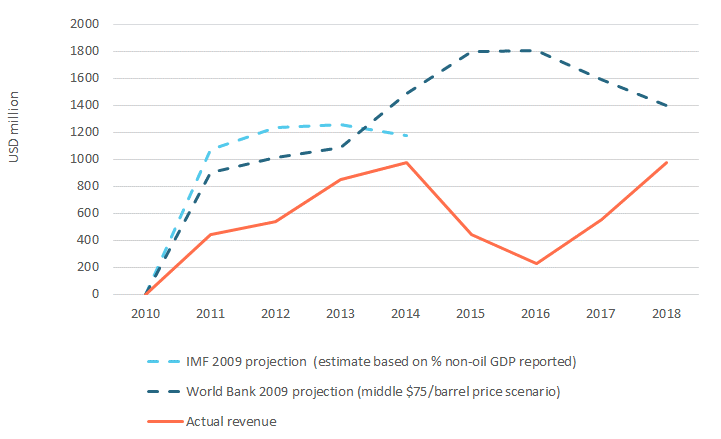

For the three countries that have managed to reach production—Ghana, Niger and Mauritania—government revenues have fallen significantly short of forecasts. In the years for which we have comparable data, Mauritania collected around 90 percent less than initially projected in 2015 and Niger collected close to 60 percent less in 2018, primarily because of production shortfalls. As the following chart shows, Ghana’s revenues were less than half of World Bank projections between 2011 and 2018 as a result of lower production, higher costs and weak tax ring-fencing.

Over the past few years, Ghana has managed to develop new fields, doubling its production since 2016. However, with this year’s sharp decline in oil prices, the government has slashed its oil revenue forecast from $1.6bn to $0.6 bn: revenue is no higher than in the early years despite the larger volumes.

Overly optimistic expectations have prompted policies that—with the benefit of hindsight—did not appear realistic even before the price crash.

For example, expectations of imminent, large oil revenues may have driven the rapid increase in Ghana, Uganda and Mozambique’s debt. Some countries established sovereign wealth funds predicated on expectations of large revenues and fears of subsequent Dutch disease.

Ghana and Mauritania are among those countries that are saving oil revenues at low interest rates while borrowing on international markets at high interest rates, while Kenya and Mozambique have plans to establish sovereign wealth funds. Several governments have also invested scarce financial and human resources in managing and participating in the petroleum sector on a scale that appears disproportionate to the benefits generated so far.

Lessons for low prices and the energy transition

Reversing these disappointments will be hard in the current context. Total’s recent expansion of its Uganda stake as well as its work to advance the development of Mozambique’s Area 1 liquefied natural gas project suggests there is still some investor appetite for oil and gas in frontier areas despite the price crash.However, this period provides a window into a future in which the world moves away from fossil fuels. The road to oil and gas riches is rapidly narrowing for some new producers. Governments, development partners such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, and other organizations must radically rethink their approaches to the sector.

- Carefully forecast sector prospects. Forecasts have been consistently over-optimistic. Government officials, development partners and other public policy professionals should conduct scenario analysis on the prospect of future discoveries, timelines and government revenues. They should account for exploration success rates in their assessments of discovery prospects. They should calibrate their timeline projections against similar projects and regional benchmarks rather than relying on company projections. Their revenue projections should account for risks such as lower production levels and permanently low prices.

- Reset public expectations. Despite government attempts in some countries to temper public expectations, citizen surveys, local civil society publications and media articles signal hopes of large and imminent benefits from the sector. With the current crisis, citizens will be aware of the turmoil facing the sector, which provides a critical opportunity for governments to reset previous expectations. Development partners should support such efforts, including by working with civil society organizations and media.

- Avoid a “race to the bottom”. Countries should not relax regulatory terms to drum up interest in licensing rounds or encourage final investment decisions without rigorous modelling of their impact on investment prospects and long-term benefits for the country. Some officials may feel the need to offer drastic concessions to influence investment decisions; the benefits that projects generate for the country may then be insufficient to compensate for the environmental and social harms that they entail.

- Envisage a non-oil national development pathway. It is increasingly possible that some countries will never reach the production stage, while countries already producing may fail to expand the sector and generate transformative benefits. Governments should define what their national development strategy would be in this scenario, and consider the policy implications of a non-oil future. A first step should be to reconsider sinking more public money into the sector and to stop making borrowing and spending decisions that rely on future oil and gas revenues.

David Mihalyi is senior economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Thomas Scurfield is Africa economic analyst at NRGI.

Authors

Thomas Scurfield

Africa Senior Economic Analyst