Cheap Oil Comes with Pros and Cons for Tunisia and Egypt

During the oil boom years earlier this decade, rising petroleum subsidies in importing countries such as Tunisia and Egypt were a constant strain on budgets—and so the collapse in oil prices has produced nuanced challenges for state-owned oil enterprises (SOEs) in both countries.

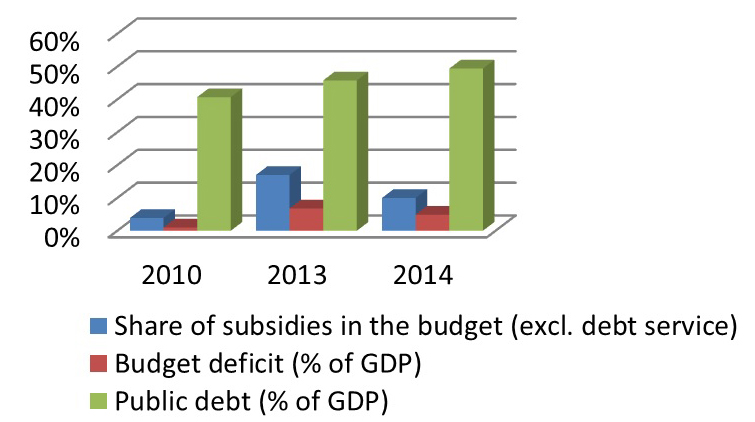

Across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, $174 billion in oil and gas subsidies have caused government deficits of up to 6.5 percent of GDP. In Tunisia, the budget deficit reached 6.8 percent of GDP in 2013, with energy subsidies consuming almost a fifth of spending. Public debt rose to 49 percent of GDP in 2014. In Egypt, the numbers were more worrying: spending on subsidies accounted for a high of 26 percent of public expenditures in 2012-2013, driving the deficit up to 13 percent of GDP. Public debt stood at 87.4 percent of GDP by the end of 2013.

Tunisia's budget performance 2010-2014

Source: Ministry of Finance and Central Bank of Tunisia

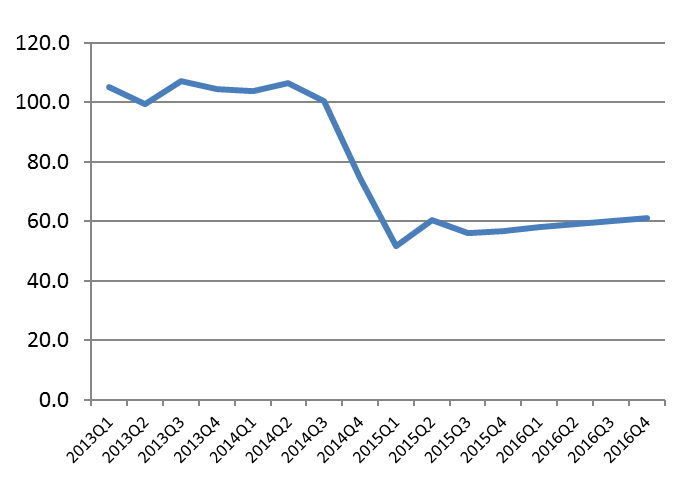

The 50 percent decline in oil prices since June 2014 should—on paper, at least—ease budget pressures for importers like Egypt and Tunisia, reducing the cost of subsidies. However, such near-term budgetary gains are at risk of being offset by revenue shortfalls in these governments' budgets, and/or expenditure slippages. In addition, because of their domestic oil production, Tunisia and Egypt may face emerging fiscal risks should state-owned companies face financial distress.

Spot crude oil price, USD per barrel

Source: IMF commodities prices, July 2015

Recent subsidy savings are precarious.

In Tunisia, the 2014 budget figures already show gains from lower oil prices. Subsidy spending has declined by around 25 percent from 2013. (Note that the Tunisia 2015 budget law uses an oil price assumption of USD 95 per barrel. This is well above the actual current price.)

Tunisia is expected to lower its deficit by at least 2 percent of GDP should oil average $65 per barrel (as of second quarter 2015, it stood at $60). Net savings from each dollar drop in the oil price are projected at $48 million; lower spending on energy subsidies outweigh the revenue losses from reduced Tunisia production royalties.

In Egypt, fuel subsidy relief is having slightly different results. The World Bank had projected spending on fuel subsidies to decline by around 25 percent (0.5 percent of GDP) year-on-year – a relief, if not a blessing, for a country with a very high budget deficit. Despite almost halving expenditures on petroleum subsidies, however, Egyptian Ministry of Finance data indicate a deficit increase of 1.8 percent of GDP. Overall expenditures picked up, driven by higher wages and, to a much lesser extent, investments and social spending.

Tunisia is expected to gain from lower oil prices in the short run. The example of Egypt, however, shows that governments must safeguard energy subsidies savings in order to boost spending on investment and targeted social programs to nudge the economy and reduce inequalities.

In July 2014, the Egyptian government unexpectedly raised prices on most petroleum products, but the process of phasing the subsidy out is still lengthy. There is also skepticism around the government's ability to translate savings into real benefits. Tunisia's announcement to increase fuel prices in May 2014 by a mere 6 percent is also an indication of the government's apprehension of popular resistance if subsidies were to be canceled. The government decision was precipitated by the IMF disbursement of a $217 million loan subject to keeping the deficit under control.

Contingent liabilities could weaken public finances.

In the private sector, cost effectiveness and efficiency maximization top the corporate priority list in a weakened oil environment. State-owned oil enterprises, however, are less prepared to weather the storm. They tend to be less efficient and to have a lower capacity to generate revenues from their production. They lack long-term investments, experience higher labor costs and undertake quasi-fiscal expenditure—such as providing social services or subsidies. Their ability to respond to negative price shocks is, therefore, hampered.

The Tunisian national oil company, ETAP, is the key player in the country's hydrocarbon sector, and generally transfers its revenues to the treasury. There are however no rules dictating the portion of revenues to be transferred or reinvested by the company. The amount of the transfer depends on the government‘s fiscal priorities, including the investment program of the company. The state is the guarantor of the company's debt.

By my calculation, using 2012 data from ETAP and the ministry of finance, government revenues from the oil sector reached 8.6 percent of total revenues, with income tax contributing to the largest share and ETAP providing more than half. In 2012, the company generated $346 million in profit, representing a buffer against loss-making activities related to the sale of subsidized products. In sum, the net cash position of the company was positive. However, it was not enough to finance investment spending, which has been highly dependent on the state. By the end of 2012, ETAP-contracted loans (excluding state loans) reached $191 million. With profitability highly correlated to the oil price, any decrease in price will only worsen ETAP's financial position. This raises the risk of contingent liabilities to the state—the company is expected to disburse around $321 million in budgeted investment spending over the coming two years.

Egypt's situation is arguably more problematic. The Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC) is highly indebted, with $ 7.5 billion (as of June 2014) in estimated outstanding debt, and opaque finances. (Despite that, the company's contribution to the treasury represented 15 percent of government revenues and 38 percent of income tax revenues.) Low oil prices further undermine EGPC. Even through the boom years, the company struggled to cover its operating costs as production decreased due to the steady decline in exploration and discoveries. The government has recently announced mega-projects in the energy sector, namely the acceleration of existing gas field development and investments worth $12.2 billion in new exploration. Here, favorable financing schemes and improved efficiency will be key to limiting exposure.

SOEs must avoid fiscal slippages in a lower price environment.

The governments of Egypt and Tunisia, like those of many other countries in the MENA region, must rethink their oil and gas sector strategies since lower prices seem to have become a new reality. That said, policy should strive to preserve and gradually increase gains from energy subsidies cuts.

Containing SOEs' quasi-fiscal activities—such as financing indirect subsidies—will make SOEs' financial position more liquid, for example giving Tunisia's ETAP the ability to respond more effectively to its investment needs. Policies should be geared toward improving the enabling environment for public-private partnership initiatives to increase investment in the space. Also, governments will be less tempted to negotiate new contract terms to attract investors, easing financial pressure on the SOEs. And any reforms must feature built-in mechanisms to ensure that the host country would fairly capture the benefits of a potential price rebound, vis-à-vis the foreign investor.

Nadine Abou Khaled is a MENA economic analyst with NRGI. She would like to thank Thomas Lassourd, economic analyst with NRGI, for his valuable comments.