Europe’s Demand for Africa’s Gas: Toward More Responsible Engagement in a Just Energy Transition

Through the publication on 18 May of its external energy strategy, the EU somewhat clarified its approach to diversifying gas supplies. The strategy is of course written from a European perspective; its implications for African producer countries require a bit of dissection. These implications are important given live debates around the role of gas in Africa’s future and more broadly, including at the G7 level.

The EU strategy (and the broader “REPowerEU” package in which it sits) indicates that Europe is seeking a short-term injection of additional gas—but also that it is accelerating its transition to cleaner energy sources. The EU is therefore unlikely to seek longer-term (post-2030) sources of gas. Current and prospective African gas producers ought to take note and adapt accordingly. If European interest in African gas is indeed primarily short-term, responsible EU-Africa engagement would require European officials to clarify their intentions and needs, and relevant African policymakers to ensure that related expectations in their countries are realistic given likely future scenarios.

With such clarity, the handful of African countries ready now (or soon) to start or increase gas production can seize a short-term opportunity to increase public revenues. But given major uncertainties around the future of gas, officials in these and other countries should focus primarily on building more sustainable economies and domestic energy systems, not investing billions of dollars of public capital in long-term gas projects that face tough obstacles and risk carbon lock-in.

There is a bigger opportunity in Europe’s energy rethink for African countries: they can use it to push the EU to follow through on its promises of financing and technology for renewable energy growth in Africa. Europe could couple the realization of these commitments with near-term gas procurement from certain African countries, contributing to long-term partnerships in service of a just energy transition.

Implications for African gas: Timing is everything

Some of the main reactions to the EU strategy have focused on important areas of climate-related concern. The strategy also brings mixed messages for policymakers in countries evaluating opportunities to export gas.

Europe’s main tool for reducing Russian gas imports will be reducing gas consumption.

The REPowerEU plan details how Europe will expedite its energy transition in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Europe’s main tool for reducing Russian gas imports will be reducing gas consumption. The plan doubles down on a previous objective to lower consumption by 30 percent by 2030 (around 100 billion cubic meters (bcm)); it details European aims to reduce consumption by a further 11 percent (35 bcm) by 2030 through a combination of energy efficiency and clean energy substitution.

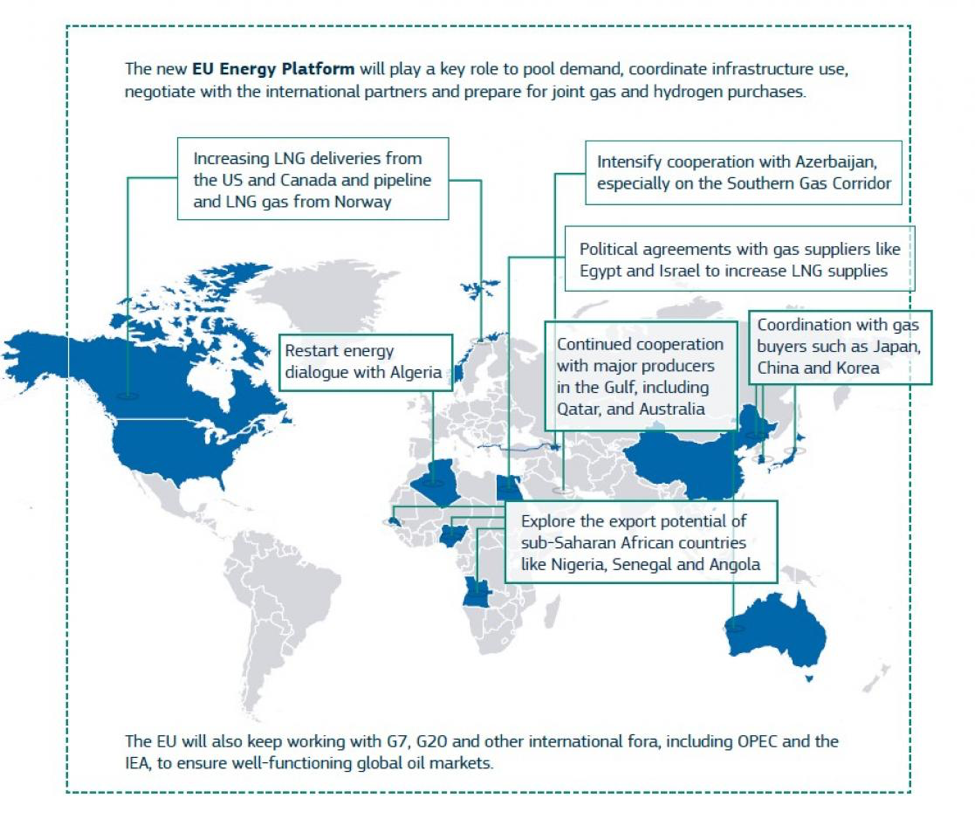

Alongside the reduction in consumption, the EU envisions an increase in gas imports from non-Russian sources: mostly of liquefied natural gas (LNG) (an additional 50 bcm), but also pipeline gas (an additional 10 bcm or more).

So, for whom is this an opportunity, and for how long? On this, the strategy is less clear.

One point of ambiguity concerns the timeframe for increased non-Russian gas imports. The strategy references the need “over the coming years” but omits further detail. Nevertheless, this will likely sync with the strengthened plans around reduced gas consumption by 2030, meaning that if the EU sticks to its decarbonization objectives it is unlikely to need much additional longer-term supply (i.e., for 2030-2050) given its 2050 net-zero target.

A second point of ambiguity relates to the prospective sources of additional supply. The EU has already advanced some deals for short-term supply, including a political agreement with the U.S. for additional LNG imports of at least 15 bcm in 2022 and approximately 50 bcm annually until at least 2030. The 50 bcm would cover all of the EU’s planned increase in LNG supply, meaning there may not be any opportunities for other producers. And yet the strategy also references separate efforts to source gas (e.g., LNG from Egypt and Israel, and piped gas from Algeria and Azerbaijan) and specifically mentions the “untapped LNG potential” of countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

And so it seems that within Africa the opportunity is for existing producers, or those with projects on the cusp of production, that can supply gas before 2030. These could include Angola, Egypt and Nigeria insofar as they can quickly ramp up production. Senegal has already sold the LNG from its initial GTA project, due to start producing in 2023, to Asian buyers, but a final investment decision on a second phase is possible within the next year and production on that phase could start within the next few years.

More generally, expansion of projects with existing infrastructure would be particularly attractive to Europe for a few reasons. It could potentially avoid signing long-term commitments that trigger investments. European officials could also argue that expansions do not constitute development of “new oil and gas fields,” which the IEA has deemed incompatible with achieving net zero by 2050. European demand is unlikely to be much of an opportunity for other countries (or other projects in the above countries) that can only export in the longer-term (2030-2050); these would clearly constitute “new production.”

Europe’s identification of other potential sources of LNG may just be insurance against the possibility that EU-U.S. negotiations fail to result in the full supply of 50 bcm—or a tactic to increase European leverage in those negotiations. Like any insurance policy, this one may not be used, and ultimately significant European demand for additional African supply may not materialize even in the near term. And it may be that Europe wants the “insurance” but isn’t willing to pay the “premium”—or at least not a very high one—in the form of long-term gas purchase agreements necessary to secure financing for projects or funding new infrastructure. If the EU does not plan to make big, long-term investments in African LNG in that way, the responsible course would be to say so explicitly now, rather than leave prospective African suppliers to interpret ambiguities in the strategy.

Officials in producing countries should note these nuances and recognize that Europe and other importers generally prefer to have a diversity of producers, though Europe’s climate considerations may temper the EU’s preference. Many producing countries may never reach the “front of the queue.” Responsible engagement by officials in producing countries would mean avoiding significant risk when jostling for position—by entering a “race to the bottom” negotiation, investing significant public capital to de-risk projects for investors, or getting locked into oversized domestic gas infrastructure that may crowd out cheaper renewable energy alternatives.

EU energy strategy: Missed opportunity on just transition?

In its strategy the EU states that a “just and socially fair” transition is integral to its external energy policy. In practice, its plans around supplier diversification seem shortsightedly agnostic as to where supplies originate—essentially anywhere but Russia.

In a truly just transition, the EU would reduce rather than increase gas imports from countries such as the U.S. and Qatar, as these wealthier countries should be among the first to cut production in a just fossil fuel phaseout. As researchers and advocates for an equitable transition are increasingly recognizing, countries with more urgent development needs should have priority within the remaining carbon budget given their lower capacity to finance their own even more challenging energy transitions. In the absence of an agreed international framework for managed phaseout of fossil fuels, such priority access for developing producers is unlikely. But the EU should support the development of such a framework—or at least apply just principles where it can, as in its international energy strategy.

If consumer countries fail to adopt good governance criteria when selecting future energy suppliers, they risk repeating the mistakes of the past, when Western companies and governments served as key enablers of Putin’s catastrophic kleptocracy. The EU has laid important groundwork on this front, with democratic values and good governance/transparency as key principles for partnerships under its Global Gateway initiative. However, plans to intensify cooperation with authoritarian regimes as part of the EU’s gas diversification strategy raise concerns about its commitment to avoid enabling corrupt regimes.

As part of a responsible engagement the EU and its prospective African gas suppliers should account for the risk that citizens in these African countries may view gas export to the EU as coming at the expense of domestic energy plans.

Developing countries’ domestic energy needs, particularly in Africa where about 600 million people (around half of the population) lack access to electricity, are essential to a just transition. The EU should prioritize delivering on its stated support for increasing renewables in such countries. The strategy’s recognition that renewable energy exports to Europe (e.g., as green hydrogen) should not adversely impact a country’s domestic energy access is significant; the EU should develop this further. But the EU strategy is noticeably silent on the potential impact of increased gas exports to Europe on domestic energy needs in gas-producing countries. This is particularly relevant for discussions around sub-Saharan African gas producers, given the significance (rightly or wrongly) assigned to gas in strategies for addressing domestic energy needs. As part of a responsible engagement the EU and its prospective African gas suppliers should account for the risk that citizens in these African countries may view gas export to the EU as coming at the expense of domestic energy plans. This could accelerate resentment as Europe uses African gas while objecting to gas-supported electrification within Africa for climate reasons.

A way forward

More broadly, the EU should redouble its engagement around ensuring a just transition for developing countries that produce, or aim to produce, fossil fuels. The strategy’s reference to these countries’ interest in exporting green energy shows that the EU appreciates the importance of replacing revenue sources that lower-income countries will lose as part of the energy transition. The EU should support such long-term “revenue smoothing.” This could be part of an Africa-EU green energy initiative inclusive of partnerships of the type launched with South Africa at COP26.

The EU and producer countries should not over-rely on the idea included in the strategy that combining gas cooperation with long-term energy cooperation on hydrogen can “avoid stranded assets and ensure the green transition.” Avoiding stranded assets should be a priority, but not based on an overly broad assumption that fossil fuel infrastructure can be repurposed for other uses.

The EU should instead avoid stranded asset risk in the first place by being as clear as possible on likely future gas demand. With that clarity, African gas-producing countries can determine whether and how they can benefit in the short-term, while avoiding the temptation to sink billions of dollars in public capital in projects predicated on long-term European demand.

Authors

Antonio Hill

Advisor

Thomas Scurfield

Africa Senior Economic Analyst

Amir Shafaie

Legal and Economic Programs Director