How the Resource Governance Index Can Be Used to Audit Extractives

As I have argued in a previous blog, supreme audit institutions are natural guardians of resource governance. They have both the legal mandate and the access—at least in theory—to be an independent check on the management of extractives all along the industry decision chain.

In Uganda, for example, the Office of the Auditor General has proven adept at responding to the unique challenges of resource extraction. The office’s most recent annual reports identified significant underpayment of gold royalties, disallowed more than USD 70 million in old oil company cost claims and called out dangerous weaknesses in the government’s management of oil data.

In just the last few weeks, article after article has covered the shocking findings of the most recent report by South Africa’s auditor general, including serious failings in the management of the state-owned oil company.

But supreme audit institutions, known as SAIs, aren’t always able to function so effectively in this space. They are often limited by insufficient funding and internal technical expertise, refused access to financial records and documentation, and even threatened over critical findings. It doesn’t help that audit reports can be intimidatingly long and complicated, or that SAIs tend to shy away from direct engagement with civil society and journalists. Luckily, there is a great group of SAI professionals committed to addressing these challenges: the INTOSAI Working Group on the Audit of Extractive Industries.

I had the pleasure of joining the group’s annual meeting in September, when I presented the 2017 Resource Governance Index and the implications of its findings. We also began to discuss how the index could be used to support SAIs’ oversight work.

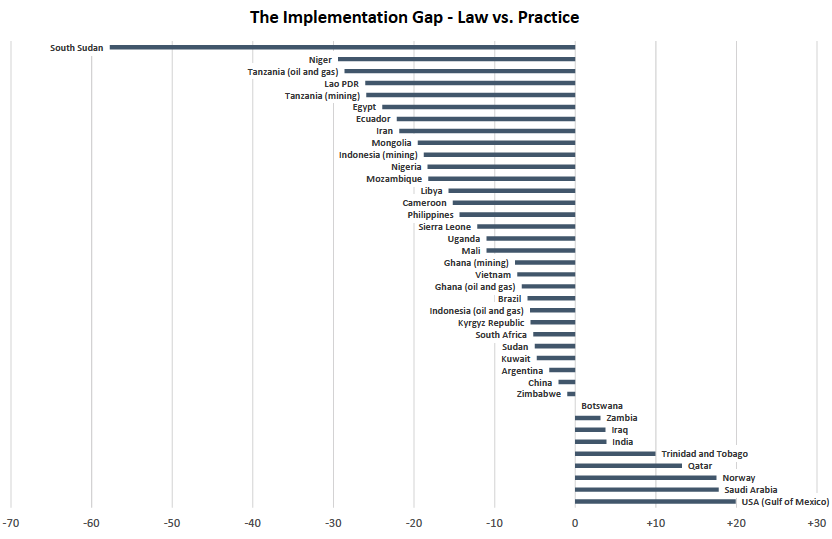

SAIs have a critical role to play in closing the “implementation gap” so well illustrated by the index. The 89 country/sector assessments included are each based on a 149-question survey completed by extractive sector and country experts, and supported by almost 10,000 documents. One of the most interesting features of this edition of the index is that it differentiates between the quality of the policies, laws, and regulations as written and the reality of implementation.

Of the 39 assessments conducted in INTOSAI working group countries, 30 noted a significant failure by governments to implement their own legal frameworks. The chart below illustrates this failure through the differences between the points scored for law questions and those for practice, negative numbers indicating that laws are much stronger than practice. SAIs can expose and make recommendations to help close these gaps through both regular and special audits. For example, a SAI can use its annual audit reports to highlight noncompliance with fiscal rules for the saving and spending of resource revenues. Or a SAI could conduct a special audit of the degree to which the government is adhering to its contract and fiscal transparency commitments.

Click here to enlarge

Click here to enlarge

SAIs can also use the Resource Governance Index country profiles and downloadable data explorer to inform their work. The country profiles provide a good general sense of how well a country’s governance systems match up against other countries and against global standards. This snapshot can help SAIs identify major risk areas, inform the objectives and scope of audits, put evidence in context and outline alternative approaches from other countries to include in the audit recommendations. The data explorer goes into much more detail on the documentation and explanations underlying the country assessments and offers many great options for examining, visualizing, and comparing the data.

Though still somewhat unknown in the extractives governance movement, SAIs are increasingly recognized as critical actors in the accountability ecosystem.

Dana Wilkins is a capacity development officer with the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).