Mining Lessons From Mongolia’s Many Revenue-Sharing Experiments

Монгол »

A few months ago, the Mongolian government promised more than 2 million Mongolian citizens a check of up to 96,480 tugrugs (USD 34).

This wasn’t a government handout. The monies are dividends Mongolians are entitled to as shareholders in a coal miner called Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi (Five Hills Treasures).

Mongolia’s policy experiments with resource-to-cash programs provide a unique perspective into public ownership and revenue sharing in the mineral sector. As governments around the world rethink the role of the state in the ongoing public health crisis, they could learn from Mongolia’s experience.

The beginning of resource-based contributions, often tied to election cycles

Mongolian citizens are used to receiving cash from the government by now. This dynamic is especially familiar ahead of parliamentary elections, such as those coming up in June.

This dynamic goes back to (at least) to the 2004 election campaign. At that time, the Democratic Party (DP) promised monthly payments of MNT 10,000 to a guardian of every child. Not to be outdone, the Mongolian People’s Party (MPP), the DP’s main rival, proposed MNT 500,000 transfers to newlywed couples and guardians of newborn children.

Ironically, the two political parties had to establish a coalition government. The DP and MPP quickly realized that these proposed payments didn’t fit the budget. Their compromise, the “Child Money Program,” provided MNT 3,000 per child per month. Initially, eligibility was limited to poor households with at least three children. The program later became universal for all children.

The initial concerns of financing such expensive programs dissipated as commodity prices shot up and Mongolia introduced the controversial, sizable windfall profits tax in 2006. The revenue from this tax went to the Fund for the Development of Mongolia. The government added MNT 25,000 per quarter transfers from this fund to every child, in addition to the MNT 3,000 that came from the state budget. Additionally, the guardian of every child born and newlywed families also received one-time grants of MNT 500,000 between 2006 and 2009.

Upping the stakes

By the 2008 election campaign, the DP and the MPP were leaning into a policy of recurring cash transfers. The DP promised to up the grant amount to MNT 1 million. Instead of targeting only children, it would apply to all Mongolian citizens. It would be branded “The Resource Share.”

The MPP initially criticized the DP move as economically unviable, only to counter with a MNT 1.5 million “motherland gift” to all citizens. Both programs were impromptu, lacking details that might or might not have actually existed. Nobody knew if these transfers would be one-off or recurring, and whether they would be in cash or other forms. While the MPP won the elections, it once again formed a coalition government with the DP.

As the global financial crisis struck the country, the government shelved cash transfers. But the electorate did not forget politicians’ promises, of course. As the economic slowdown quickly dissipated on the back of a mining investment boom, expectations of resulting mineral revenues grew high.

The government established a new fund to collect mining revenues. Established in 2010, the Human Development Fund was tasked with starting new cash transfer programs to replace the child-oriented payments, at a much larger scale. The new program replaced annual MNT 120,000 payments with monthly MNT 21,000 payments per person between 2010-2012. Fittingly, the transfers were called “gifts and shares” to mimic the election promises of both parties. In 2012, the elderly received an additional one-off MNT 1 million payment.

This spending frenzy coincided with a breathtaking period of growth for Mongolia. GDP grew at an average 13.7 percent per year over 2011-2013 period. This was also the period when Mongolia started borrowing on the international capital markets, with USD 1.5 billion infusion from an inaugural sovereign bond issue in 2012.

The spigot is shut

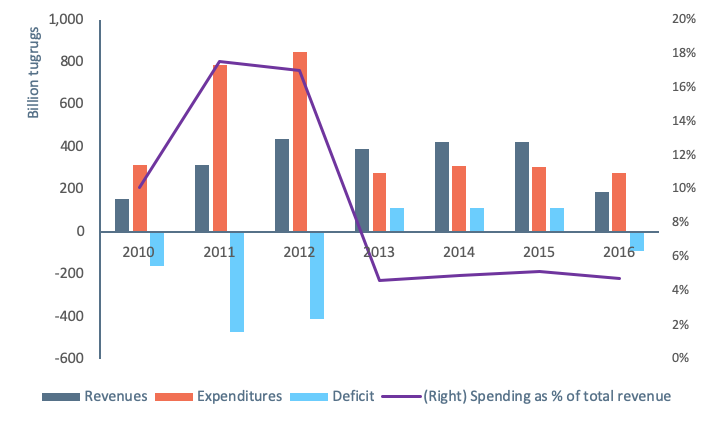

Over the next years, Mongolia’s growth slowed and the debt situation deteriorated significantly. One contributor was the Human Development Fund, which spent up to 18 percent of total government revenue in 2012. Revenues it collected from mining sector were about half that, leading to massive deficits within the fund. (See figure.)

After the 2012 elections, the government pared back cash transfers. It stopped paying out universal handouts, and went back to targeting children only (MNT 20,000 per month). This temporarily restored the fund’s balance.

On top of that, in demonstration of its commitment to restoring fiscal sustainability, parliament adopted the Future Heritage Fund Law in early 2016. It established a sovereign wealth fund to start saving mineral revenue instead of spending it through cash handouts. As the Human Development Fund books were closed, it had debts equaling a whopping MNT 1.071 trillion, which were transferred to this new fund. Only in 2019 did the Future Heritage Fund come out from under its predecessor’s debt. The Future Heritage Fund could actually start accumulating savings.

Human Development Fund in 2010-2016

Source: Ministry of Finance, Human Development Fund Performance, www.mof.gov.mn

Mongolia had to negotiate a bailout package with IMF at the beginning of 2017 and committed to restrict the child-related transfers to the poorest. But from 2019, the government returned to the universal coverage, at MNT 20,000 per month per child. In May, before June elections, the government announced it will increase this to MNT 100,000 per child, at least for a six-month period. It justified this measure as a method to mitigate economic impact from the coronavirus pandemic.

Cash handouts, especially for children, seem destined to continue for the foreseeable future, mainly as a political vote winner. However, another former vote winner, direct cash transfers to every citizen, is criticized widely by the opposition and economists as not having significant long-term benefits and siphoning funds for much-needed public investments.

Manifold resources-to-cash schemes

Resources-to-cash schemes in Mongolia have abounded, given their political usefulness and calls for more equitable benefits of mining.

At the peak of the spending frenzy in 2011, the government decided to privatize 20 percent of Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, a company managing a massive coal deposit on the state’s behalf. Each citizen received 1,072 shares in the company. Back then, the company was saddled with debt, which was used in part to fund cash transfer programs. For many years, the mining company kept servicing its debt through proceeds from exports to coal-hungry China. Since repaying its debt in 2017, the company became more profitable, and in 2019 it made nearly MNT 1 trillion in profits.

The initial idea was in 2011 was to give out another 10 percent of shares to domestic businesses. Another 20 percent would be floated on stock exchanges. To date, these ideas have not materialized. And since handing out shares to citizens in 2011, there have also been some twists and turns. For instance, the elderly, who received MNT 1 million in cash just before the 2012 elections, had to give up their shares in exchange. Students could use half of their shares in exchange for MNT 491,960 in tuition fees in 2011. Some citizens could trade shares for health insurance coverage. All citizens could voluntarily exchange a third of their shares for MNT 300,426 in cash through a stock repurchase program that was another way to distribute cash to citizens just prior to the 2016 elections. Though the idea was floated, citizens were not allowed to sell their shares other than back to the government through these repurchase programs.

In the end, about a third of Mongolians (about 1.08 million people) held on to all of their 1,072 shares, and are eligible for a full dividend payout of MNT 96,480 (USD 34). Those who sold back their shares got proportionally less.

The dividends have an important side benefit. There is a lot more scrutiny into Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi management and state-owned miners in general. For instance, a “1,072 shares” movement demanded the company hold open shareholder meetings, declare dividends and provide detailed information on company performance. The company itself established an information center and a hotline focusing on the 1,072 shares.

Others have called for increasing citizens’ stake in the company and applying similar schemes for other state-owned enterprises (SOEs). But whether this leads to wider reforms of SOEs and improves their performance remains to be seen. The state remains the dominant shareholder, with almost 85 percent of Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi. The government makes the decisions that affect the profitability of the company and sets dividends. The fact that citizens cannot sell their shares and that a large part of the population lacks financial literacy are hard facts curbing initial enthusiasm about citizen capacity for monitoring.

The future trend?

Mongolia has experimented with many ways to distribute proceeds from its vast mineral sector to its citizens. Initially understandably popular, cash transfers have proven disappointing. While promising to increase them has been a powerful way to win votes, these promises turned out expensive and fiscally unsustainable when commodity prices fell.

Therefore, politicians attempted to restrain themselves by explicitly prohibiting the inclusion of agendas “to allocate gifts, shares, or their equivalents to citizens from mining, oil, mineral or other sector revenues” in any election platforms in the Election Law of 2019. However, the word “dividend” is not mentioned, and “shares” in the company rather than from “mineral revenues” are totally legitimate. As such, transferring shares of state-owned companies to all citizens and handing cash as dividends in case of profits might be on the rise in the coming years.

More fundamentally, the willingness of politicians to go miles to invent new ways of delivering cash to citizens is a sign of general dissatisfaction with the ways mineral resources benefited ordinary citizens. The sector has failed to lift people from poverty and failed to provide jobs and opportunities to and for the population at large. Many associate these poor outcomes with inefficient and corrupt government spending, and see direct cash transfers as a solution. Owning shares in mining companies creates the legal basis, and equally importantly, the perception of being a beneficiary of the country’s mineral endowments.

But whether citizens can use their shares to demand a better managed resource sector remains a question. And whether demand for coal wanes and puts the value of Mongolian shareholders at risk is another question entirely.

Dorjdari Namkhaijantsan is Mongolia manager at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). David Mihalyi is a senior economic analyst at NRGI.

Photo by Usukhbayar Gankhuyag on Unsplash.

A few months ago, the Mongolian government promised more than 2 million Mongolian citizens a check of up to 96,480 tugrugs (USD 34).

This wasn’t a government handout. The monies are dividends Mongolians are entitled to as shareholders in a coal miner called Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi (Five Hills Treasures).

Mongolia’s policy experiments with resource-to-cash programs provide a unique perspective into public ownership and revenue sharing in the mineral sector. As governments around the world rethink the role of the state in the ongoing public health crisis, they could learn from Mongolia’s experience.

The beginning of resource-based contributions, often tied to election cycles

Mongolian citizens are used to receiving cash from the government by now. This dynamic is especially familiar ahead of parliamentary elections, such as those coming up in June.

This dynamic goes back to (at least) to the 2004 election campaign. At that time, the Democratic Party (DP) promised monthly payments of MNT 10,000 to a guardian of every child. Not to be outdone, the Mongolian People’s Party (MPP), the DP’s main rival, proposed MNT 500,000 transfers to newlywed couples and guardians of newborn children.

Ironically, the two political parties had to establish a coalition government. The DP and MPP quickly realized that these proposed payments didn’t fit the budget. Their compromise, the “Child Money Program,” provided MNT 3,000 per child per month. Initially, eligibility was limited to poor households with at least three children. The program later became universal for all children.

The initial concerns of financing such expensive programs dissipated as commodity prices shot up and Mongolia introduced the controversial, sizable windfall profits tax in 2006. The revenue from this tax went to the Fund for the Development of Mongolia. The government added MNT 25,000 per quarter transfers from this fund to every child, in addition to the MNT 3,000 that came from the state budget. Additionally, the guardian of every child born and newlywed families also received one-time grants of MNT 500,000 between 2006 and 2009.

Upping the stakes

By the 2008 election campaign, the DP and the MPP were leaning into a policy of recurring cash transfers. The DP promised to up the grant amount to MNT 1 million. Instead of targeting only children, it would apply to all Mongolian citizens. It would be branded “The Resource Share.”

The MPP initially criticized the DP move as economically unviable, only to counter with a MNT 1.5 million “motherland gift” to all citizens. Both programs were impromptu, lacking details that might or might not have actually existed. Nobody knew if these transfers would be one-off or recurring, and whether they would be in cash or other forms. While the MPP won the elections, it once again formed a coalition government with the DP.

As the global financial crisis struck the country, the government shelved cash transfers. But the electorate did not forget politicians’ promises, of course. As the economic slowdown quickly dissipated on the back of a mining investment boom, expectations of resulting mineral revenues grew high.

The government established a new fund to collect mining revenues. Established in 2010, the Human Development Fund was tasked with starting new cash transfer programs to replace the child-oriented payments, at a much larger scale. The new program replaced annual MNT 120,000 payments with monthly MNT 21,000 payments per person between 2010-2012. Fittingly, the transfers were called “gifts and shares” to mimic the election promises of both parties. In 2012, the elderly received an additional one-off MNT 1 million payment.

This spending frenzy coincided with a breathtaking period of growth for Mongolia. GDP grew at an average 13.7 percent per year over 2011-2013 period. This was also the period when Mongolia started borrowing on the international capital markets, with USD 1.5 billion infusion from an inaugural sovereign bond issue in 2012.

The spigot is shut

Over the next years, Mongolia’s growth slowed and the debt situation deteriorated significantly. One contributor was the Human Development Fund, which spent up to 18 percent of total government revenue in 2012. Revenues it collected from mining sector were about half that, leading to massive deficits within the fund. (See figure.)

After the 2012 elections, the government pared back cash transfers. It stopped paying out universal handouts, and went back to targeting children only (MNT 20,000 per month). This temporarily restored the fund’s balance.

On top of that, in demonstration of its commitment to restoring fiscal sustainability, parliament adopted the Future Heritage Fund Law in early 2016. It established a sovereign wealth fund to start saving mineral revenue instead of spending it through cash handouts. As the Human Development Fund books were closed, it had debts equaling a whopping MNT 1.071 trillion, which were transferred to this new fund. Only in 2019 did the Future Heritage Fund come out from under its predecessor’s debt. The Future Heritage Fund could actually start accumulating savings.

Human Development Fund in 2010-2016

Source: Ministry of Finance, Human Development Fund Performance, www.mof.gov.mn

Mongolia had to negotiate a bailout package with IMF at the beginning of 2017 and committed to restrict the child-related transfers to the poorest. But from 2019, the government returned to the universal coverage, at MNT 20,000 per month per child. In May, before June elections, the government announced it will increase this to MNT 100,000 per child, at least for a six-month period. It justified this measure as a method to mitigate economic impact from the coronavirus pandemic.

Cash handouts, especially for children, seem destined to continue for the foreseeable future, mainly as a political vote winner. However, another former vote winner, direct cash transfers to every citizen, is criticized widely by the opposition and economists as not having significant long-term benefits and siphoning funds for much-needed public investments.

Manifold resources-to-cash schemes

Resources-to-cash schemes in Mongolia have abounded, given their political usefulness and calls for more equitable benefits of mining.

At the peak of the spending frenzy in 2011, the government decided to privatize 20 percent of Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi, a company managing a massive coal deposit on the state’s behalf. Each citizen received 1,072 shares in the company. Back then, the company was saddled with debt, which was used in part to fund cash transfer programs. For many years, the mining company kept servicing its debt through proceeds from exports to coal-hungry China. Since repaying its debt in 2017, the company became more profitable, and in 2019 it made nearly MNT 1 trillion in profits.

The initial idea was in 2011 was to give out another 10 percent of shares to domestic businesses. Another 20 percent would be floated on stock exchanges. To date, these ideas have not materialized. And since handing out shares to citizens in 2011, there have also been some twists and turns. For instance, the elderly, who received MNT 1 million in cash just before the 2012 elections, had to give up their shares in exchange. Students could use half of their shares in exchange for MNT 491,960 in tuition fees in 2011. Some citizens could trade shares for health insurance coverage. All citizens could voluntarily exchange a third of their shares for MNT 300,426 in cash through a stock repurchase program that was another way to distribute cash to citizens just prior to the 2016 elections. Though the idea was floated, citizens were not allowed to sell their shares other than back to the government through these repurchase programs.

In the end, about a third of Mongolians (about 1.08 million people) held on to all of their 1,072 shares, and are eligible for a full dividend payout of MNT 96,480 (USD 34). Those who sold back their shares got proportionally less.

The dividends have an important side benefit. There is a lot more scrutiny into Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi management and state-owned miners in general. For instance, a “1,072 shares” movement demanded the company hold open shareholder meetings, declare dividends and provide detailed information on company performance. The company itself established an information center and a hotline focusing on the 1,072 shares.

Others have called for increasing citizens’ stake in the company and applying similar schemes for other state-owned enterprises (SOEs). But whether this leads to wider reforms of SOEs and improves their performance remains to be seen. The state remains the dominant shareholder, with almost 85 percent of Erdenes Tavan Tolgoi. The government makes the decisions that affect the profitability of the company and sets dividends. The fact that citizens cannot sell their shares and that a large part of the population lacks financial literacy are hard facts curbing initial enthusiasm about citizen capacity for monitoring.

The future trend?

Mongolia has experimented with many ways to distribute proceeds from its vast mineral sector to its citizens. Initially understandably popular, cash transfers have proven disappointing. While promising to increase them has been a powerful way to win votes, these promises turned out expensive and fiscally unsustainable when commodity prices fell.

Therefore, politicians attempted to restrain themselves by explicitly prohibiting the inclusion of agendas “to allocate gifts, shares, or their equivalents to citizens from mining, oil, mineral or other sector revenues” in any election platforms in the Election Law of 2019. However, the word “dividend” is not mentioned, and “shares” in the company rather than from “mineral revenues” are totally legitimate. As such, transferring shares of state-owned companies to all citizens and handing cash as dividends in case of profits might be on the rise in the coming years.

More fundamentally, the willingness of politicians to go miles to invent new ways of delivering cash to citizens is a sign of general dissatisfaction with the ways mineral resources benefited ordinary citizens. The sector has failed to lift people from poverty and failed to provide jobs and opportunities to and for the population at large. Many associate these poor outcomes with inefficient and corrupt government spending, and see direct cash transfers as a solution. Owning shares in mining companies creates the legal basis, and equally importantly, the perception of being a beneficiary of the country’s mineral endowments.

But whether citizens can use their shares to demand a better managed resource sector remains a question. And whether demand for coal wanes and puts the value of Mongolian shareholders at risk is another question entirely.

Dorjdari Namkhaijantsan is Mongolia manager at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). David Mihalyi is a senior economic analyst at NRGI.

Photo by Usukhbayar Gankhuyag on Unsplash.

Authors

Dorjdari Namkhaijantsan

Mongolia Manager