New Database Reveals Prominence of Tax Incentives in Mining

Tax incentives granted to mining companies are debated across the globe.

Whether granted by law or through long-term stabilized agreements, communities in resource-rich countries question whether tax incentives deprive them of the full value of their country’s extractive resources. Why? Because unrealized mining revenue often contrasts with the lack of vital public resources and infrastructure.

In Senegal, where close to half of the population lives under the poverty line and annual tax revenue only accounts for 15 percent of GDP, tax incentives have cost the country around USD 400 million to 500 million in foregone mining revenue, according to Ousmane Cisse, Director of Mines and Geology of Senegal’s Ministry of Mines and Industry. However, companies that benefit may argue that incentives are required to encourage large capital investments in projects with high levels of financial and operational risk. Better data could help inform some of these debates at the national and international levels.

For this reason, the publication of the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF) Mining Tax Incentives Database on July 24 is welcome news. The database is a collection of files comparing the fiscal regimes of 104 mining projects across 21 countries; it is the first large-scale, systematic attempt to compile tax incentives used by developing country governments to attract mining investment.

It is also the first public effort to list and compare incentives granted in mining contracts, drawing from 104 of the more than 2,000 documents available on the public repository resourcecontracts.org. This comparison is the result of greater contract transparency, which the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and other international organizations have supported for many years.

The database suggests a number of valuable lessons, four of which are highlighted below.

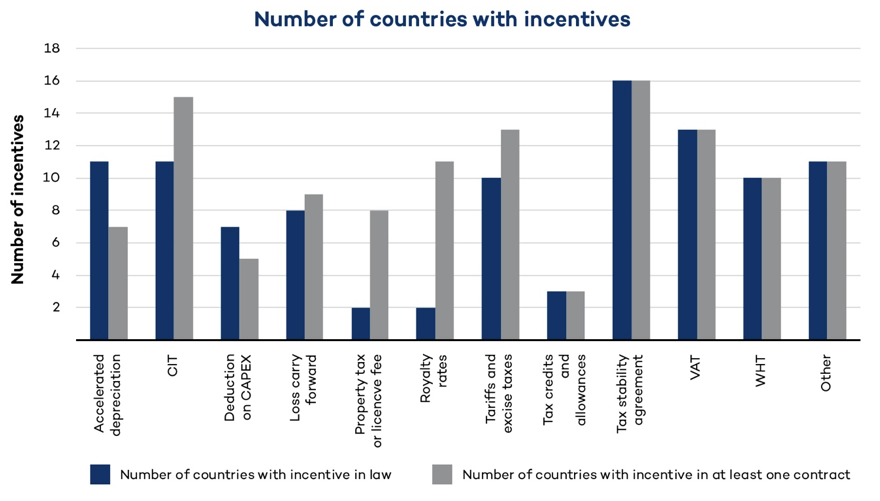

- Contrary to public perception, we discovered it is more common for countries to grant incentives in the law, such as mineral or tax codes, than in project-specific contracts—except for reduced royalty rates, which are more often found in contracts.

- The most common incentives offered to companies by governments are tax stabilization and corporate income tax incentives, followed by withholding tax incentives. Together, these generate the highest level of risk to revenue, especially as the average tax holiday in the database lasts nine years.

- Surprisingly, cost-based incentives, in particular investment allowances and tax credits, are uncommon, despite being more efficient in attracting mining investments than profit-based incentives.

- On average, taxes are stabilized for 20 years through stabilization provisions in law or contracts. A complete review of the database is available in a dedicated briefing.

These findings are by no means exhaustive and are based on the still-limited coverage of the database. Further analysis of the database by policy-makers, researchers, international organizations and civil society actors will yield additional lessons for the design and use of mining tax incentives. To ensure that the contents remain relevant, and in light of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) requirement for member countries to publish all resource contracts by 2021, IGF will periodically update the database and welcomes support from researchers and partner organizations in this task.

The content of the database can already inform a number of policy discussions. First, the database is part of a series of materials on mining tax incentives and complements the IGF-OECD practice note, Tax Incentives in Mining: Minimising Risks to Revenue, as well as the open-source IGF financial model for estimating the cost of tax incentives. Together, they offer tools and policy ideas for mineral-rich governments that may want to review mining-sector tax incentives. The database complements other work by international financial institutions on tax expenditure, investment competitiveness and tax incentives beyond the mining sector, as well as work by the Tax Justice Network. It will also be useful to the UN subcommittee on extractive taxation as its members update the Handbook on Selected Issues for Taxation of the Extractive Industries by Developing Countries. Tax researchers may use the database or adapt its methodology to pull even more relevant data from publicly available resource contracts.

For citizens in countries covered by the database, this summary data on tax incentives could ignite important national debates on tax policy. In it they can find answers to questions like: Did Guinea’s government reduce the number and length of income tax holidays in mining contracts following the adoption of a new mining code in 2013? Does state-owned company Gécamines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo contribute to the awarding of tax incentives to companies in which it has a stake? Will it undermine the controversial amendment of the mining code in 2018? Are the contractual terms of tax incentives in Zambia taken into account in the country’s already complex mining tax policy?

Mineral resources are collectively held assets that should not be squandered. A vigorous, informed domestic and international debate on the prevalence and effectiveness of tax incentives in the mining sector should be a priority for mineral-rich countries.

Want to learn more? Watch the recorded IGF webinar “The Cost of Tax Competition in Mining.”

Alexandra Readhead is a technical advisor on tax and extractive industries at IGF. Jaqueline Terrel is a program officer for tax and extractive industries at IGF. Thomas Lassourd is a senior economic analyst at NRGI.

This post also appears on IGF’s website.