Paradox of Plenty, Redux: Azerbaijan Grapples with Low Oil Prices

“This is such a disaster for us,” an Azerbaijani citizen told a reporter in December. “How come they decided to bankrupt people in one night?”

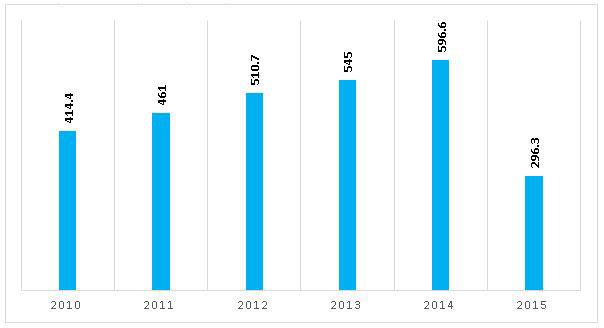

He was reacting to the decision of Azerbaijan’s central bank to free-float the national currency in late December 2015, after which the manat lost 32 percent of its value against the U.S. dollar (new exchange rate: USD 1=AZN 1.5). Prices shot up and several banks went out of business.

Socially vulnerable groups, especially the elderly and youth, have suffered most: “I spent two hours going around pharmacies trying to find my medication,” said one school teacher in Baku.

After Azerbaijan decided to float its currency, wages, pensions and social allowances paid in manat lost almost half of their value in U.S. dollar terms. Several private and state-run enterprises announced job cuts.

Azerbaijan: Monthly average wages in USD

Source: State Statistical Committee of Azerbaijan; CESD, “The Economy of Azerbaijan in 2015: Independent View,” January 2016

As in other oil-producing states, the oil price crash diminished government export revenues. In Azerbaijan, a share of profit oil goes to the state oil company SOCAR, while 80 percent of profit oil, bonus payments and transit fees is deposited in the state oil fund (SOFAZ). The government also collects revenue in the form of profit tax on foreign oil companies. In the midst of the oil price collapse, total government revenues from oil contracts fell from USD 16.7 billion in 2013 to USD 9.5 billion in 2015.

In 2016, the state oil fund SOFAZ is expected to collect AZN 4.6 billion (USD 3 billion) in revenue, continuing a pattern of decline from the previous year. The government’s ability to finance social programs and infrastructure is now in question. Most public investment projects financed through the state budget and SOCAR itself have been cut.

SOCAR is in dire straits. The company initially announced that the oil crash halved its revenues and recently revealed that it made no profit last year. Meanwhile, it accumulated USD 6.3 billion in debt.

What went wrong?

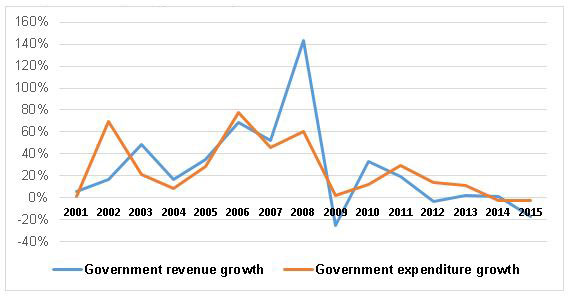

Researchers from the Eurasia Extractive Industries Knowledge Hub at Baku’s Khazar University devoted a special issue of the Caucasus Analytical Digest to low oil’s impact on Azerbaijan’s economy. They found the main reasons for the current economic recession lie in the government’s poor spending choices during the oil boom, driven by rampant rent-seeking. The key idea here is what economists call “pro-cyclical fiscal policy,” which basically means that authorities indulge in a spending spree in boom times and cut spending when resource earnings go south, prioritizing short-term interests over long-term development goals.

Ideally, a fiscal rule, like that used by Norway, would delink revenue flows from expenditures – saving more during good times to smooth the effects of future commodity price shocks. During the oil boom, Azerbaijan did the opposite, aligning its spending decisions with the price of oil (as demonstrated in the figure below). The absence of a fiscal rule means there is no formal requirement as to how much should be saved. Azerbaijan’s informal rule (not always observed) has been that 25 percent of oil revenues should be saved and up to 75 percent could be spent.

Pro-cyclicality and a short-term mentality are also behind the poor quality of public investments. Oil revenues could have spurred the development of non-oil sectors and helped the country mitigate the current recession’s social costs. Instead, the government spent billions on grandiose sports stadiums; the European Games hosted by Baku in June 2015 costed at least USD 1.2 billion of budget money, although the real cost is likely to be as much as USD 8 billion. The Olympic Stadium, which was built for USD 600 million, now stands idle and is now being offered for rent for weddings. Despite the plunge in oil revenue, Baku has allocated USD 202 million for hosting international sporting events this year. A Formula 1 race and a chess event are the only two in 2016..

Unfortunately, the oil boom was another missed opportunity. As the good times are gone, it is likely that there will be even less incentives for investments in human capital accumulation and creation of fair rules for private sector development.

Pro-cyclical fiscal policy in Azerbaijan

Source: International Monetary Fund WEO

Government responses

Although the oil price collapse caught the government off guard, authorities responded to the external shock by drawing down fiscal savings, tightening its monetary policy and imposing some currency controls such as limiting the sale of foreign currency and a 20 percent tax on foreign currency outflows. The president later revoked this decision.

Social spending has not been affected so far. However, dwindling fiscal reserves, the under-developed private business sector and a large youth bulge will put further strains on the government’s ability to provide for jobs and social welfare in the longer run.

First, the sovereign wealth fund and its USD 34 billion in assets provided a comfortable cushion. The government is to use the extra-budgetary savings (AZN 10.7 billion, or USD 7.1 bln this year), and while the amount transferred to the state budget was reduced in absolute terms, the transfer accounts for some 45 percent of total budget revenues in the projected 2016 budget. Yet, the state fiscal reserves are not limitless: Azerbaijan is running out of oil and cannot replenish funds later. The oil reserves will be fully depleted in 15 years from now, and since gas is priced lower than oil, it will generate only a small fraction of export profits in the future.

On the monetary front, the central bank devalued the national currency twice last year and then shifted from the fixed exchange rate to the managed floating regime. Having burnt through more than half of its foreign currency reserves in 2015 (from about USD 14 billion in 2013-14 to USD 5 billion in 2015 and USD 4.1 billion as of May 2016), it has been able to restore some monetary stability. However, the cost of living has increased. It is the poor and middle classes that suffered most. Prices of imported consumer goods went up and official inflation rate has already reached 10.8 percent in the first quarter of 2016.

Thus far, the sense is that the government has chosen to “wait and see” and hope the oil price returns to earlier peak levels. If the oil price stays low, the government will face more taxing times ahead.

Transparency and accountability in allocation of resource revenue is a need. An important first step toward this goal is adopting a clear fiscal rule to tackle arbitrary withdrawal of money from the state oil fund and a gradual introduction of performance-based budgeting in which funds are tied to execution and outcomes. The participation of civil society groups is also crucial to ensure oversight over implementation.

Download Low Oil Prices: Economic and Social Implications for Azerbaijan.

Farid Guliyev is a research associate and project coordinator at the Eurasia Regional Extractive Industries Knowledge Hub in Baku, Azerbaijan. Follow the Eurasia Hub on Twitter.