Peru's Political Crisis Produces New Attempts to Lower Mining Standards

Español »

Last month a political crisis flared in Peru after members of congress voted to impeach then-president Martin Vizcarra, in what most citizens considered a legislative coup. People took to the streets to protest the new government headed by president of congress, Manuel Merino. Demonstrations, which lasted over a week, were the largest the country had seen in decades and provoked police brutality, resulting in the killing of two young men and over a hundred people wounded. This in turn led to Merino’s resignation, leaving the country temporarily without a president, and the eventual election by the congress of a new president, Francisco Sagasti.

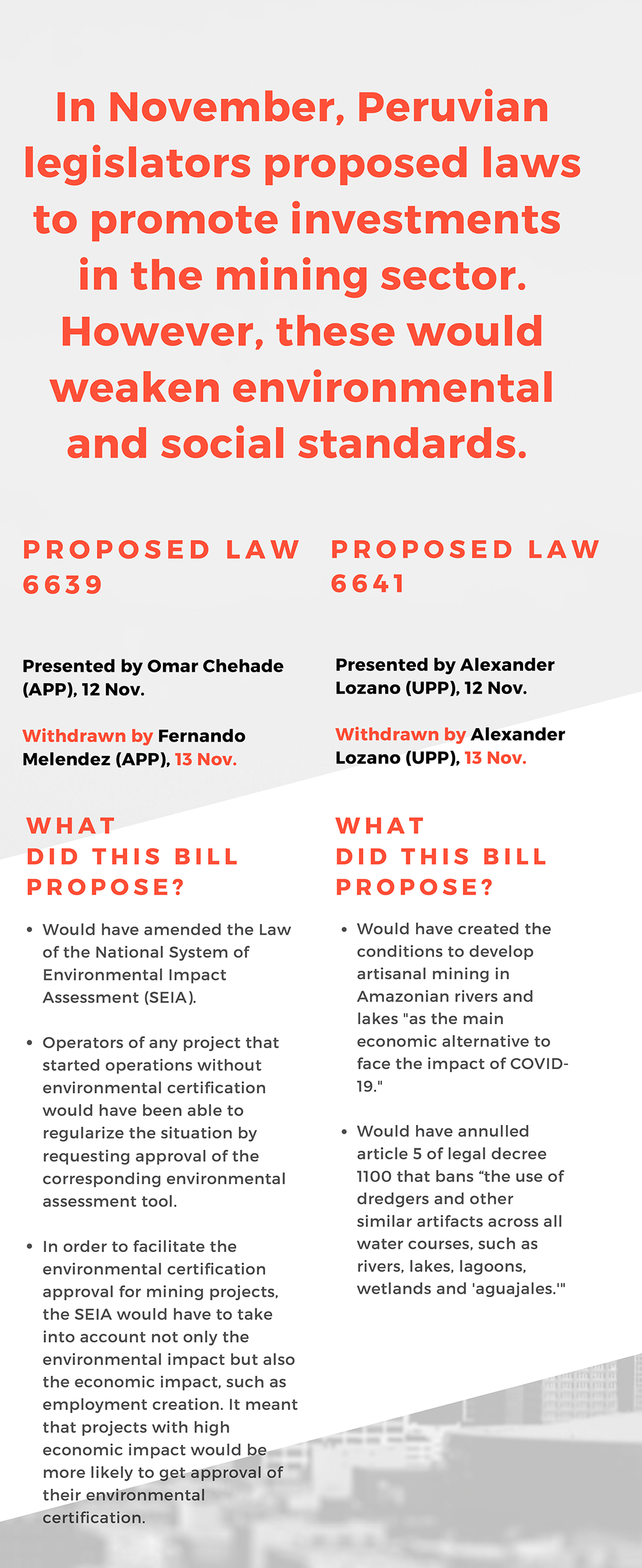

Amid this political crisis, two congressmen who were part of the parliamentary coup presented bills that proposed highly detrimental changes to Peru’s environmental assessment system, and deregulated artisanal and alluvial gold mining in the Amazon. Neither was made law, but these changes would have reversed environmental standards that were years in the making. It would have also diminished the government’s power to prevent and monitor environmental impact of extractive activities, including mining in a biodiverse and therefore vulnerable area, such as the Amazon. Furthermore, the bills’ sponsors never offered any proof that lower environmental and social standards would in fact lead to higher investment.

The first bill (proposed law 6639) aimed to modify the “Law of the National Environmental Impact Assessment System.” Among the most concerning changes, the bill would have allowed projects that had started to operate without environmental certification to obtain retroactive approval. In addition, operators of existing projects would have been able to modify or enlarge operations by simply submitting a request for environmental certification, without needing to wait for approval.

The second (law proposal 6641), sought to promote alluvial gold mining in the Amazon “as the main alternative economic activity against the impact of Covid-19.” It proposed to eliminate prohibitions in the current law on the use of heavy machinery (dredgers) that have a high environmental impact and cause deforestation.

NRGI, in coordination with civil society allies organized as the Peru-Colombia CSO Platform for a Sustainable Recovery, reviewed the bills and commented on social media about the dangers they entailed. Due to pressure from CSOs, and a context of citizen mobilization against congress, the legislators who presented them withdrew both bills.

Later, after president Sagasti took office, the newly appointed minister of mines quickly announced simplified and shorter processes for indigenous consultation for mining exploration. In addition, legislators presented more bills that threaten environmental safeguards, e.g., a bill to cut 400 hectares of a protected area in favor of an irrigation project. Although not directly related to the mining sector, this could set a dangerous precedent for investment projects that overlap with protected areas.

These moves reveal intentions to lower governance standards in order to facilitate investments and use of resources in Peru. All this comes at a time when the country faces simultaneous health, economic and political crises. Although the appointment of the new president and cabinet provided a relative calm, the next few months will be far from quiet. Presidential elections are coming up in April and the actors that perpetrated the coup will likely again attempt to seize power. The health and economic crises related to the coronavirus pandemic continues to put pressure on the new transition government to promote a swift economic recovery. Officials see the mining sector a key sector for this recovery, but growth in mining investment simply cannot come at the cost of weakened governance in the sector.

Image of Yanacocha mine by Golda Fuentes (CC licence 2.0)

Last month a political crisis flared in Peru after members of congress voted to impeach then-president Martin Vizcarra, in what most citizens considered a legislative coup. People took to the streets to protest the new government headed by president of congress, Manuel Merino. Demonstrations, which lasted over a week, were the largest the country had seen in decades and provoked police brutality, resulting in the killing of two young men and over a hundred people wounded. This in turn led to Merino’s resignation, leaving the country temporarily without a president, and the eventual election by the congress of a new president, Francisco Sagasti.

Amid this political crisis, two congressmen who were part of the parliamentary coup presented bills that proposed highly detrimental changes to Peru’s environmental assessment system, and deregulated artisanal and alluvial gold mining in the Amazon. Neither was made law, but these changes would have reversed environmental standards that were years in the making. It would have also diminished the government’s power to prevent and monitor environmental impact of extractive activities, including mining in a biodiverse and therefore vulnerable area, such as the Amazon. Furthermore, the bills’ sponsors never offered any proof that lower environmental and social standards would in fact lead to higher investment.

The first bill (proposed law 6639) aimed to modify the “Law of the National Environmental Impact Assessment System.” Among the most concerning changes, the bill would have allowed projects that had started to operate without environmental certification to obtain retroactive approval. In addition, operators of existing projects would have been able to modify or enlarge operations by simply submitting a request for environmental certification, without needing to wait for approval.

The second (law proposal 6641), sought to promote alluvial gold mining in the Amazon “as the main alternative economic activity against the impact of Covid-19.” It proposed to eliminate prohibitions in the current law on the use of heavy machinery (dredgers) that have a high environmental impact and cause deforestation.

NRGI, in coordination with civil society allies organized as the Peru-Colombia CSO Platform for a Sustainable Recovery, reviewed the bills and commented on social media about the dangers they entailed. Due to pressure from CSOs, and a context of citizen mobilization against congress, the legislators who presented them withdrew both bills.

Later, after president Sagasti took office, the newly appointed minister of mines quickly announced simplified and shorter processes for indigenous consultation for mining exploration. In addition, legislators presented more bills that threaten environmental safeguards, e.g., a bill to cut 400 hectares of a protected area in favor of an irrigation project. Although not directly related to the mining sector, this could set a dangerous precedent for investment projects that overlap with protected areas.

These moves reveal intentions to lower governance standards in order to facilitate investments and use of resources in Peru. All this comes at a time when the country faces simultaneous health, economic and political crises. Although the appointment of the new president and cabinet provided a relative calm, the next few months will be far from quiet. Presidential elections are coming up in April and the actors that perpetrated the coup will likely again attempt to seize power. The health and economic crises related to the coronavirus pandemic continues to put pressure on the new transition government to promote a swift economic recovery. Officials see the mining sector a key sector for this recovery, but growth in mining investment simply cannot come at the cost of weakened governance in the sector.

Claudia Viale is a Latin America senior officer at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Image of Yanacocha mine by Golda Fuentes (CC licence 2.0)

Authors

Claudia Viale

Latin America Senior Officer