Resource Governance Index Points to State-Owned Enterprises as Key Mongolia Reform Target

Note: This post is a modified version of one originally written for the Mongolia Thoughts blog hosted by the University of British Columbia.

NRGI’s Resource Governance Index (RGI) measures governance in the extractives sectors of 81 countries. This year, Mongolia’s mining sector ranked 15th among 89 assessed country extractive sectors, with an overall score of 64 out of 100 points—a “satisfactory” result indicating that progress has been made in some areas of resource governance. Good governance of extractives is a critical precondition for sustainable development in resource-rich countries, and Mongolians would do well to use the index’s findings as a roadmap in their efforts to plan and implement necessary reforms.

A glass half-full or half-empty?

Global indices like the Resource Governance Index often provide a single overall country score that is a composite of many component and subcomponent scores. While there can be many merits to this approach, a composite score might conceal problem areas if the relative significance of subcomponents is not properly captured, or if scores for some well-performing indicators sharply contrast to those for problematic areas. The index’s assessment of Mongolia provides a clear example of the latter, and it is worthwhile to explore issues that are obscured by Mongolia’s satisfactory overall score.

Mongolia’s results are mixed: the score indicates that the country has strong governance procedures and practices in some areas, but needs improvements in others.

The index measures governance across three components. The first is value realization, which covers issues related to licensing, taxation, local impact and state-owned enterprises—factors determining whether a country gets an expected return for the use of its resources. The second component is revenue management, which covers issues related to government budgeting, subnational revenue sharing and management of revenues through different wealth funds. The third component draws on pre-existing measures of governance and assesses a country’s enabling environment—the extent to which the country creates an environment conducive to transparent and effective policies. While Mongolia scored relatively well on the enabling environment component (73 points of 100), its scores for revenue management (54) and value realization (63) indicate that there is much room for improvement, especially on the two components that are directly related to the benefits the country derives from its extractive industries.

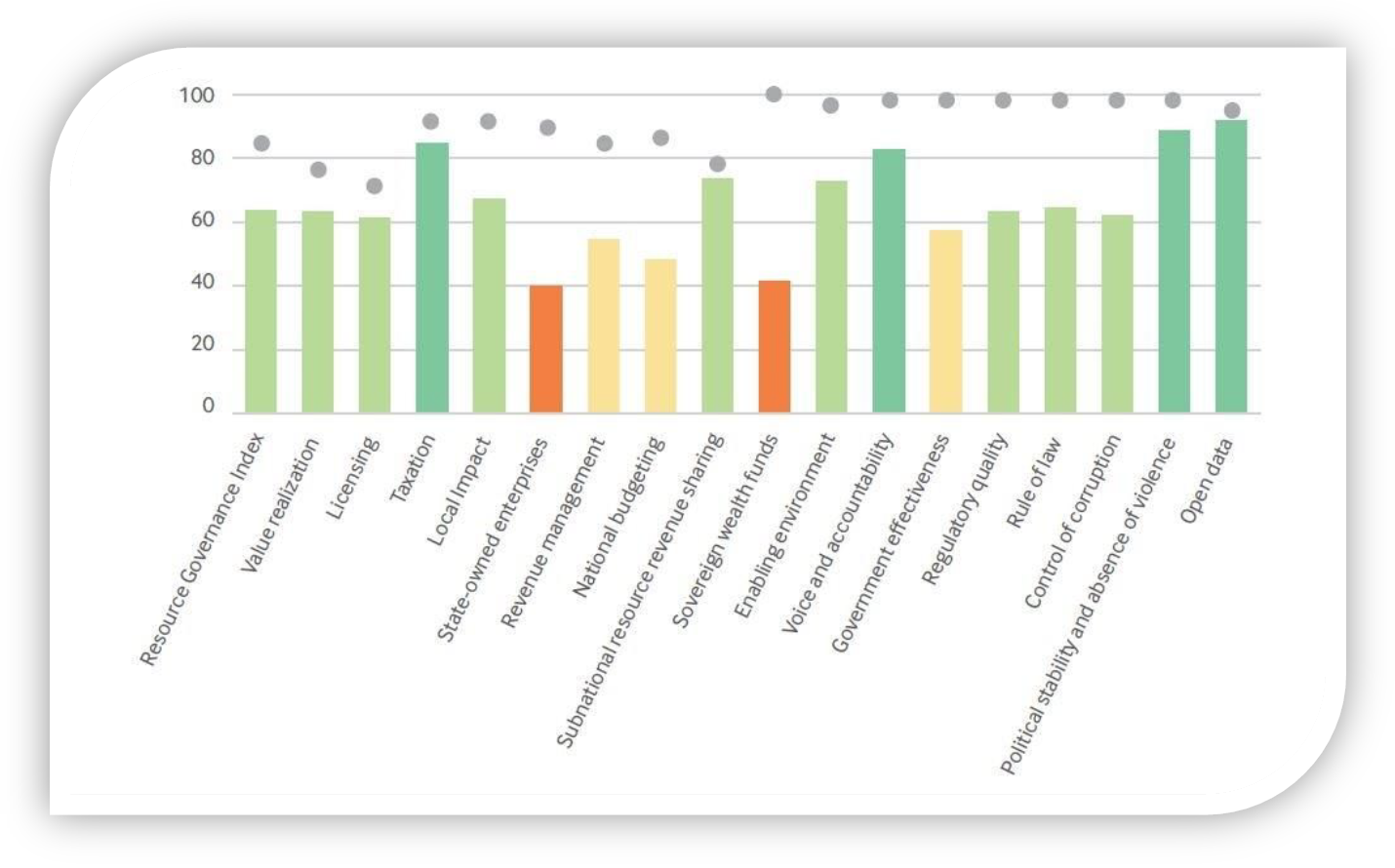

Digging deeper reveals even more discrepancies among subcomponents. (See chart below.) For instance, the lowest subcomponent score is for state-owned enterprise governance (40 points of 100), while the highest score is for open data policies (92). The 52-point gap between the two subcomponent scores highlights the need to take a more holistic approach to strengthening extractives governance. The key issues impacting governance of the sector are highly interrelated. Indeed, even one unaddressed issue may result in the failure of the overall policy.

Mongolia scores for Resource Governance Index subcomponents

Notes: Dots represent global maximum scores for each component. Dark green, light green, yellow and amber indicate good, satisfactory, weak and poor performance, respectively.

Notes: Dots represent global maximum scores for each component. Dark green, light green, yellow and amber indicate good, satisfactory, weak and poor performance, respectively.

The index reveals a big “implementation gap” between rules related to extractives governance and the practice of implementing these rules. On average, the score for all legal frameworks assessed by the index (54 points of 100) exceeds the score for practical implementation (45). This gap is even larger for Mongolia—20 points. Weak implementation of policies and laws has always been a challenge for Mongolia. Sayings like “Mongolian laws last three days” are well known, even by school children. The index confirms what many Mongolians already know. The enforcement of laws and regulations related to transparency and accountability is especially weak. The Glass Account Law or Open Government Partnership commitments are just two examples.

Focus on details

Public demand for greater transparency and accountability in the Mongolian mining sector has led to many reforms in the past two decades. Such progress—including the implementation of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative—has positively impacted Mongolia’s overall Resource Governance Index score and contributed significantly to the volume of extractives-related information people can access.

Despite its strong overall score, the devil is in the details. The government should continue working to increase transparency and accountability. One key area of concern revealed by the index is the governance of state-owned enterprises, in particular that of Erdenes Mongol, the largest state-owned holding company. This company holds the country’s strategic mining assets, so improved governance of Erdenes Mongol can have a profound effect on the wider economy. However, at present, the company does not make essential information (such as annual financial reports) publicly available, and it ranks quite low in comparison to similar entities in other countries. Unlike governance challenges that depend on factors beyond a government’s control such as commodity price volatility, reform of state-owned enterprises largely depend on political will.

Mongolia’s mining revenue management can be improved via prudent budget spending and better sovereign wealth fund management. The government devised the Fiscal Stability Fund and the Future Heritage Fund[LB1] for this very purpose, but both bodies still exist purely on paper. As indicated by high deficits and the threat of defaults, the government budget remains unstable. Mongolia has not managed to conserve portions of its mining revenues for future generations, which is a result of politically motivated spending and shrinking revenues. Rules governing these funds change much too often, and there is little publicly available information or scrutiny on these funds’ policies.

Extractive company beneficial ownership disclosure and improved transparency around extractive contracts are two other needs. The former is a relatively new challenge that, if addressed effectively, can help end ownership anonymity, build trust with the public, and prevent tax evasion and corruption. The latter is a long-standing challenge in Mongolia. Both these issues are also a part of Mongolia’s commitments under the OGP and EITI. Most importantly, these reforms would both lead to a more level playing field for investors and ensure that the benefits from the sector trickle down to all Mongolians.

Dorjdari Namkhaijantsan is the Mongolia manager for the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Authors

Dorjdari Namkhaijantsan

Mongolia Manager