Senegal and the G7: Five Questions about the Just Energy Transition Partnership

A French-language version of this post appeared as a commentary piece in La Tribune Afrique on 24 June 2022.

Senegalese President Macky Sall is expected to attend the G7 Summit in Germany from 26 to 28 June. This will be an opportunity to engage in the ongoing discussion between the Senegalese government and the ambassadors of the G7 member countries in Dakar on establishing a “just energy transition partnership” (JETP). The JETP builds on South Africa’s energy transition partnership announced at COP26 in Glasgow, which is still under negotiation.

Unlike South Africa and several of the countries targeted by the G7 for a possible JETP, such as Indonesia and India, Senegal is neither a major coal producer or consumer, nor a major polluter. Instead, Senegal is primarily a future gas producer, whose production will be important for both domestic and export markets. While the opportunity for climate finance for Senegal presented by the JETP is to be welcomed, the motivations and potential content of such an agreement should be examined, insofar as these discussions are taking place in the geopolitical context of an overhaul of European energy policy as a result of Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Public debate should address five questions in the coming weeks:

1. How will the JETP ensure better access to energy for Senegalese citizens?

Senegalese citizens will expect that a potential JETP will help meet the country’s energy needs and support its economic development. Senegal relies on its gas reserves to achieve its goal of universal access to electricity by 2025. In this sense, the partnership could support the financing of gas-to-power projects in the country that would not otherwise be financed, but also (and especially) the development of renewable energy projects.

2. What is the role of Senegalese gas exports to Europe under the JETP and which gas projects will be targeted for this purpose?

This question leaves much room for speculation, including that the nascent JETP has been established solely as an alibi for exporting Senegalese liquefied natural gas to the EU. Although the first phase of the GTA project, which is expected to start production in 2023, has already been promised to Asian buyers, the second phase, for which a final investment decision (FID) is expected within the next year, remains an option for supplying the European market. However, the Mauritanian government’s weak participation in ongoing talks with Senegal, despite the two countries sharing the gas field, suggests that the Europeans may be eyeing another, exclusively Senegalese gas field: Yakaar-Teranga. This project, which is close to a final investment decision, would be an excellent candidate for supplying the European market, except for the fact that its first phase is planned to supply the local market. The Sangomar oil project, which comes on stream in 2023, will also generate gas in later phases (which have not yet achieved FID). This would be associated gas, requiring significant processing before marketing, which would entail additional investment.

3. If Europe is going to secure its gas supplies through the JETP, how will it finance these projects?

The financing of gas projects is a stated priority of the Senegalese government in the JETP discussions, but it is a goal made difficult by Europe’s aversion to long-term gas purchase agreements in light of climate commitments. It is therefore important to pay particular attention to how any financing of gas projects under the JETP will be structured to avoid excessive risk being allocated to Senegal in order to attract the necessary investment.

4. Will the JETP involve agreements not to exploit some of Senegal’s gas, like South Africa’s JETP, which targets a phase-out of coal?

A JETP should balance the objectives of decarbonization, energy access and maximizing Senegalese revenues. Important elements for Senegal to consider in this regard are the approach to later phases of gas projects and new exploration, and support for renewables and energy access, including financing and technical assistance for grid extension, improving the stability of electricity supply or integrating clean technologies into polluting sectors. In the case of agreements involving the non-exploitation of gas, the JETP should promote compensation (direct or indirect) to replace the sources of revenue that Senegal will lose.

5. What support is there for any alternatives to gas exports under consideration?

The JETP may promote collaboration on green hydrogen, which is also a focus for Senegal. Given the uncertainties around the economic and technical feasibility of green hydrogen exports, the Senegalese government should be careful not to rely too heavily on this prospect that is rather distant for the time being.

The answers to these questions are of interest to the Senegalese, but not only the Senegalese. This potential JETP is an interesting proposition because it offers a potentially transformative just transition model for emerging gas-producing countries. Conversely, failure could slow down the momentum of these countries toward energy transition.

Authors

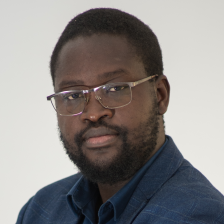

Papa Daouda Diene

Africa Economic Analyst