In the Shadow of Letpadaung: Stories from Myanmar's Largest Copper Mine

This photo essay is from a series that documents the lives of communities affected by the extraction of natural resources in Myanmar.

The scale of the Letpadaung copper mine was overwhelming, even from a distance. Looking down on the site from the outskirts of a nearby village, I could see stripes of copper lining the walls of the pit while small trucks, about the size of ants from where I stood, steadily made their way across the mine. Much of this land had once belonged to farmers. I spoke with locals who had lost their livelihoods to copper operations, and many referred to the mine as a burden that continues to weigh on the local community.

Thawe Thawe Win, a 31-year-old farmer and activist in the Sagaing region, pumps water out of the well at the edge of her village which overlooks the Letpadaung copper mine. Thawe Thawe Win's family once owned ten acres of land until mine developers took eight of the ten acres in 2011 -- without providing compensation to the family. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

The Letpadaung mine is located about an hour away from Monywa, in Myanmar’s Sagaing region. I arrived in a nearby village in July 2015 to meet with Thawe Thawe Win, a 31-year-old woman who is actively leading a protest movement against the Letpadaung mining project. We met at her family’s modest home in the late afternoon. Her confidence and tenacity were instantly palpable as she barreled into the yard on a motorbike, grinning widely and speaking emphatically into her cell phone. After exchanging pleasantries, she instructed my translator and me to follow her. I tried my best to keep up as she skillfully navigated a small path to a well at the edge of the village, which provided a panoramic view of the mine.

Phyu Phyu Win, Thawe Thawe Win's sister, stands in front of her family's home in the Sagaing region of Myanmar. Phyu Phyu Win was one of the victims of the attacks in June 2012 when the security forces clashed with a group of protesters. She still has visible scars on her face and body from the attack. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

Beginning in 2011, thousands of people were forcibly evicted from their land in order to make way for the mine, which is operated by the Chinese company Wanbao Mining Copper Ltd. and majority-owned by the Myanmar government. Thawe Thawe Win’s farmland was located on the border of the mining site. She explained how the Letpadaung partners seized eight of her ten acres—without compensation. Her family’s finances, like many others, have been strained by the loss of their land and their former way of life.

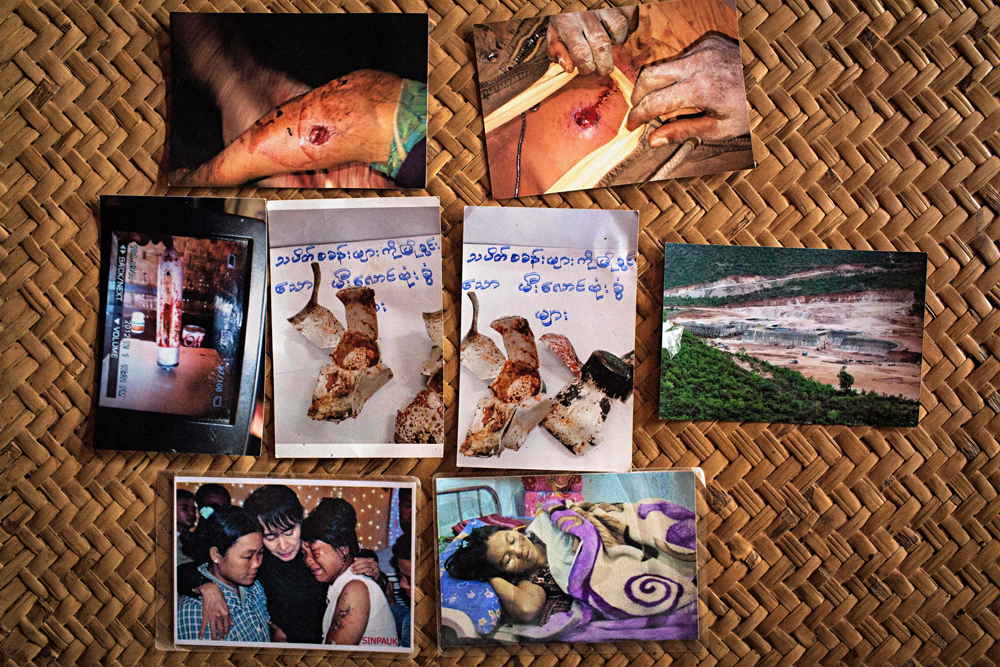

Thawe Thawe Win's family keeps photographic evidence of the June 2012 attacks, showing injuries, photos of her sister recovering, and an image of Aung San Suu Kyi visiting the victims of the attacks. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

Thawe Thawe Win has had the opportunity to attend international conferences in Thailand and Indonesia on land rights, which have allowed her to take a leading role in educating her community. She now helps negotiate fair rates for private land purchases in her village and examines court cases and police hearings regarding attacks on citizens by security forces.

Freelance miners carry buckets of water, which they collected from small puddles, to sift and extract copper from the gravel taken from the Letpadaung mine property. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

Protests against the mine have repeatedly been met with excessive force by police. I went with Thawe Thawe Win to visit Aung Myint Htwe, 37, who leads a monastery in Shwe Hlay village. He described a night in November 2012, when Myanmar police and private security forces attacked villagers and monks protesting the operations at Letpadaung. Aung Myint Htwe explained that protesters who set up camp at the facility’s gates were told at 2:45 AM to go home. He described how at 3:15 AM, when the protesters had not vacated the entryway, police cornered them and sprayed water and burning white phosphorous. The clash injured more than 100. Thawe Thawe Win’s younger sister, Phyu Phyu Win, was left with permanent facial scars.

A young girl sits at the top of a pile of coppery stones at the edge of the Letpadaung copper mine. The stones are routinely carried down the mountain by freelance miners hoping to extract as much copper as possible. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

Daw Khin Win, a 56-year-old widow, was fatally shot in the head when police opened fire on protestors at the Letpadaung site in December 2014. Thawe Thawe Win brought me to the police hearing to meet the family members who were seeking justice for Daw Khin Win. Unfortunately, it seems unlikely that Myanmar’s bureaucracy will compensate these relatives. I was thoroughly questioned, and had to provide passport and visa information to authorities at every turn; the special branch police kept their camera phones pointed steadily in my direction.

Old tin cans serve as a magnet for the copper as it is extracted and sifted from the stones. The process takes 20 days and will earn one family about $100. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

About 30 minutes outside of Monywa, Kankone village has also been impacted by Letpadaung’s development. Kankone’s independent miners, who once numbered more than 1,000, must now illegally enter the Letpadaung property in order to collect copper-rich soil. Fear is ever-present in the village—fear of not earning enough money to survive the coming months, or fear of being arrested for trespassing. Currently, miners make up to $100 per family every 20 days.

Nwe Nwe Aung, 39, holds raw copper after it has been extracted from the stones mined by her husband. Old tin cans serve as a magnet for the copper as it is extracted and sifted from the stones. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

Several residents of Kankone took me on a hike up to the top of a nearby mountain which they visit to gather stones. Young children held my hands, helping me to navigate the unclear path. Suddenly, I was pushed into a cluster of bushes and told to hide while my translator and other companions hurried down the mountain. A truck full of Wanbao Mining personnel drove past to survey the area. Had my translator or I been caught, the entire community may have been endangered.

Young children of the freelance miners gaze out at the expansive Letpadaung copper mine. Many of these children work with their parents to carry heavy stones from the top of the mountain down to the manual filtration systems their parents have set up. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

With the lands surrounding Letpadaung are diminishing, the lives of the villagers are increasingly unstable. For example, the number of independent miners in Kankone – who used to enjoy unrestricted access to nearby mineral deposits – has dwindled to a mere 40 in recent years. What lies in store remains uncertain, while injustice, insecurity, and poverty continue to mark the lives of local families.

A young girl hides in the bushes at the top of the mountain near the Letpadaung mine. As company personnel drive past, I hide alongside the local freelance miners, hoping not to be caught—which could mean fines or jail. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

Dark clouds loom overhead as freelance miners patiently wait by their extraction sites, making sure the process goes as planned. Since the development of the Letpadaung mine, the numbers of freelance miners has gone from over one thousand to a mere 40. Those still mining are worried that soon their livelihoods will be gone forever. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

A freelance miner spreads gravel in his family’s filtration site as the evening rolls in. Each miner is up with the sun and works until dusk trying to sift as much copper as possible from the earth in hopes of providing for his family. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI

Lauren DeCicca is an American freelance photojournalist based in Yangon, Myanmar, and a member of the 2015 Getty Reportage Emerging Talent roster.

The views she expresses here are her own, and do not represent NRGI. NRGI does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article. NRGI accepts no liability for any errors, omissions or representations.