Sovereign Wealth Funds: Guidance for Policymakers

A sovereign wealth fund (SWF) should serve a purpose; this seems obvious. Yet time and again, as I discussed in my previous blog, funds are established with no clear purpose, or fail to achieve their stated objectives.

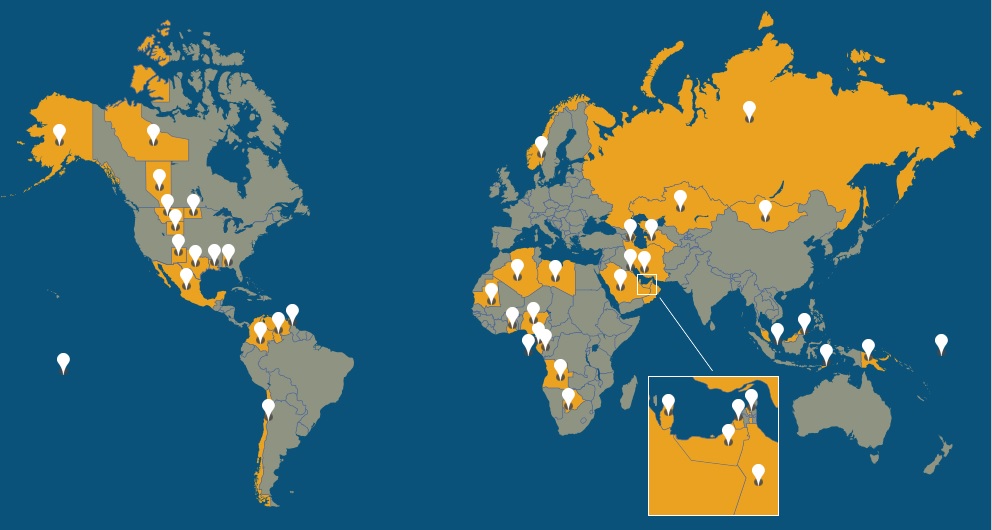

More than 50 natural resource funds have been established in over 40 countries.

The Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund in Canada, for instance, was designed in part to save oil revenues for future generations, yet it failed to save anything in all but two years between 1987 and 2012. And despite Trinidad and Tobago's Heritage and Stabilization Fund's mandate to mitigate the negative effects of oil revenue volatility on the country's budget, it led to worse public investment decisions and slower growth than would have been the case had the fund worked as planned. Elsewhere, as in Kuwait and

Libya, SWFs became channels for corruption and patronage, diverting billions of dollars away from social service and infrastructure spending.

In short, SWFs by themselves do not guarantee sound macroeconomic management. In fact, they may complicate budget processes and make public spending less accountable. So why do many international advisors and development partners still hail SWFs as a solution to the "resource curse," often without a full appreciation of the risks involved?

SWFs can be useful, but only if they help fulfill at least one macroeconomic objective, such as mitigating the impact of oil or mineral revenue volatility on government spending, or "parking" oil windfalls until they can be spent more efficiently. A global study of natural resource funds by the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment (CCSI) found that there are two pre-conditions for funds to function as planned: Appropriate rules must be enacted, and there must be adequate oversight and enough broad-based consensus to ensure compliance with those rules.

What are "appropriate" rules? While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, our joint study offers guidance.

Deposit and withdrawal rules:These determine the timing, amount and conditions for the sovereign wealth fund's inflows and outflows, either to or from the government's main bank account. In some cases, these rules are the operational form of a macroeconomic framework. For instance, Norway's rule (based on political consensus, not legislation) that the non-oil structural deficit cannot exceed four percent of GDP determines how much money flows from its SWF to the central government account. In other cases, these rules are more ad hoc, such as Kazakhstan's presidential decree that annual transfers from the national fund to the budget be fixed at $8 billion per year, plus or minus 15 percent.

Withdrawal and deposit rules must be tight enough to constrain government spending but loose and flexible enough to withstand political pressures to spend more. For instance, Timor-Leste enacted a rule that only allowed its government to spend 3 percent of petroleum wealth in any given year. This rule was too restrictive given the country's capital scarcity, high poverty levels and the high social rate of return on domestic investment. As a result, the rule has consistently been broken. Further guidance on deposit and withdrawal rules can be found here.

Investment risk limitations:SWFs hold public assets to improve macroeconomic management or for safekeeping. As such, governments should not be allowed to gamble with these funds and their asset portfolios should reflect their purpose. For example, a petroleum fund designed for stabilizing budget expenditures would require more liquid assets than a savings fund designed to benefit future generations since the government might need to draw on these assets if oil revenues collapse unexpectedly. Guidance on investment strategies for SWFs can be found here.

Regardless of the asset allocation used, SWFs should be explicitly prohibited from investing in certain high risk assets, such as junk bonds. Governments also must monitor conflicts of interest and set clear investment guidelines. Where there is inadequate oversight and rules are unclear, it is often too easy for investment managers to invest with political allies, family or friends.

Equally, following the precedents set by Abu Dhabi (UAE), Botswana, Chile, Kazakhstan and Norway, among others, legislation should strictly prohibit SWFs from investing domestically. Spending directly out of the SWF could bypass the normal budget process, including parliamentary, auditor, media or citizen oversight. This could result in inconsistencies with the budget and circumvention of controls and safeguards such as project appraisal, public tendering and project monitoring. In Angola, Azerbaijan, Iran and Russia, SWFs have been used as secondary budgets, becoming easy sources of patronage or financing for investments that support the political goals of fund managers.

Institutional structure: There should be a clear division of responsibilities between the legislature, president or prime minister, the fund manager, the operational manager and external managers to help funds meet their objectives and prevent corruption. Again, there is no standard solution, but guidance can be found here.

Transparency: Disclosure requirements should be legislated. Bodies like parliaments, fiscal councils, and the media cannot perform their oversight functions unless they have access to adequate and verifiable information. The Alaska Permanent Fund (USA) is a model of transparency, which has helped to reduce conflict over the distribution and management of Alaska's petroleum resources. A checklist of recommended disclosures can be found here.

Even the best rules will not be followed unless there is ex ante broad-based consensus on these rules and ex post effective and independent oversight of SWFs. Rules established only between governments, international financial institutions and expert advisors alone are not likely to survive a political transition or even minor pressure to break the rules. Compliance is ultimately a political problem, and as such requires a political response.

Cognizant of this reality, the Ghanaian government took the initiative when, prior to the enactment of the Petroleum Revenue Management Act, it carried out extensive public consultations, including a national survey on how Ghana should manage its petroleum revenues, regional town-hall meetings, and appeals to experts, civil society and the diplomatic community for technical advice. These consultations gave Ghanaians and internationals a sense of buy-in and stewardship over the law. A similar exercise is currently underway in Canada's Northwest Territories, which has just established a Heritage Fund to invest mineral revenues.

Oversight with teeth once all the rules are in place is equally important for compliance. External audits and constant monitoring by parliament, the media and formal bodies like Norway's Supervisory Council or Ghana's Public Interest and Accountability Committee, are not nice-to-have additions but rather essential components of successful fund governance. Independent oversight bodies can encourage good financial management by praising compliance with the rules. They can also discourage poor behavior by managers by imposing punitive measures ranging from naming-and-shaming to fines or imprisonment. Ultimately, the effectiveness of independent oversight will depend on the power of the supervisory bodies' carrots and sticks.

Andrew Bauer is an economic analyst at NRGI.

Note: This post is an adaptation of one that originally appeared on the International Monetary Fund's Public Financial Management blog.