Tanzania Strikes a Better Balance with its Mining Fiscal Regime

Key messages

In 2017, alongside other changes to the fiscal regime and wider laws for the mining sector, the government removed VAT refunds on raw mineral exports. It subsequently interpreted “raw minerals” for this purpose as essentially anything not refined in Tanzania.

VAT is intended as a tax on consumption that the final consumer of a good or service ultimately pays – whether they are based locally or in a foreign country. As part of this system, governments refund companies that pay VAT on inputs during the production process. It is therefore common for countries to provide VAT refunds on mineral exports.

The government’s removal of VAT refunds was likely partly an attempt to incentivize domestic processing. But the economic viability of more processing in Tanzania will vary for different minerals and will depend on both the type of mineral and processing conditions in the country. Few countries are able to fully refine all the minerals that they produce.

Most current and future mines will not have been eligible for VAT refunds, including several projects that are in the pipeline but yet to proceed. Peak Resources’ plan for a rare earth mine involves refining in the United Kingdom, not Tanzania. OreCorp’s prospective gold mine would export doré, which tends to be at least 80 percent pure but is not refined. Jervois Mining’s application for the development of the Kabanga deposit – which has the potential to make Tanzania one of the world’s largest nickel producers – refers to processing concentrates, but not refining.

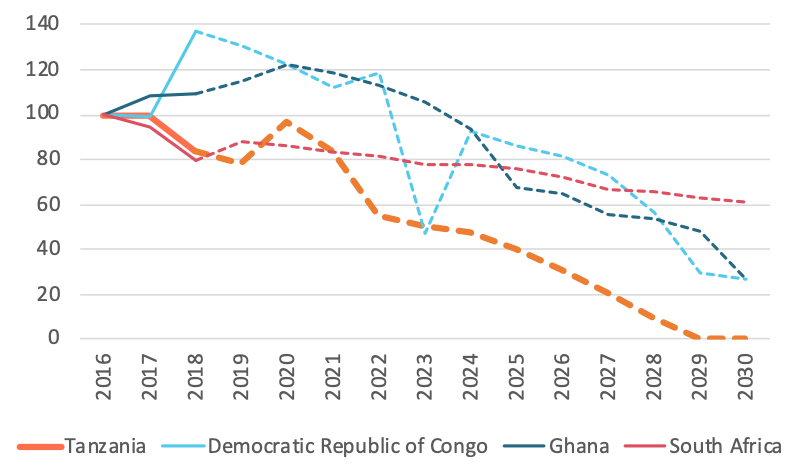

Investment in new mines is critical. In the most recent year that all of Tanzania’s mines were operating at full capacity, 2016, mining contributed 3 percent of government revenue and 37 percent of exports (this was prior to a recently lifted ban on copper concentrate exports from Barrick’s Bulyanhulu and Buzwagi mines). The country’s large-scale gold mines accounted for 90 percent of this revenue, 90 percent of exports and directly employed nearly 8,000 Tanzanians. But current investment plans for these mines provide for production only up to 2028 (according to S&P Global data). Therefore, without investment to extend these mines’ lives and develop new mines, the sector and the benefits it generates for Tanzania will shrink, rather than grow, over the next decade.

Actual and projected gold production by existing large-scale mines in Tanzania and other regional producers (normalized so 2016 production is 100 for each country)

Source: S&P Global

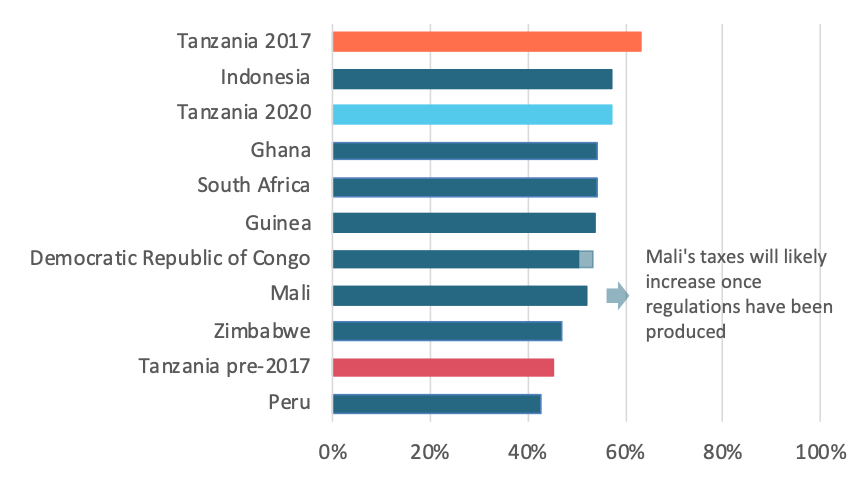

Until last week’s announcement, the prospects for significant amounts of new investment were very uncertain. As our earlier analysis highlighted, the government was right to increase taxes in 2017. However, its removal of VAT refunds resulted in taxes that were significantly higher than other countries, particularly for less profitable mines. The new regime failed to strike the right balance between generating government revenue and competitiveness.

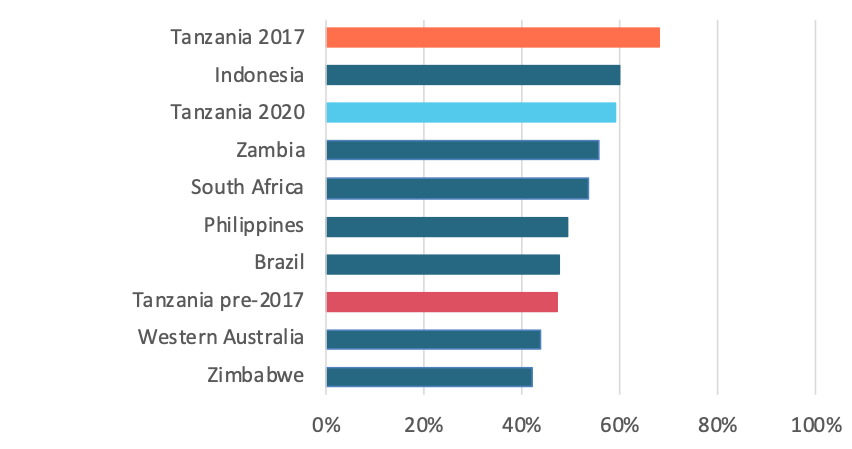

Our modeling of the fiscal regime for gold and nickel mines shows that the reintroduction of VAT refunds brings the tax level more in line with other countries, while still generating significant government revenue.

Average effective tax rate for large gold mine with gold price of $1,400 per ounce

Average effective tax rate for large nickel mine with nickel price of $17,000 per tonne

Notes: Our calculations in the NRGI mining tax models for Tanzania are published alongside this analysis. We assumed a discount rate of 10 percent. The darker area for the Democratic Republic of Congo shows the tax level when its excess profits tax is not triggered, and the lighter area when its excess profits tax is triggered (with a 25 percent price differential). For Zimbabwe, we assumed that mines operate under an ordinary mining license rather than a special mining license given, that all but one large-scale mine currently does so.

Tanzania could make further improvements. Even with the reintroduction of VAT refunds, Tanzania’s taxes are less responsive to mine profitability than most other regimes that we analyzed. The government could therefore consider a royalty rate that varies with prices. This would provide some relief to mines when prices are low, and capture more revenue for government when prices are high.

The government could also revisit its plan for minority equity in projects. A change here would not be to improve the regime’s competitiveness but rather ensure that the government collects the revenue it expects. As the experiences of Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo show, minority state equity often does not generate government revenue – at least partly because it is more exposed to tax avoidance risks than other taxes. Given the government can achieve the non-fiscal benefits of state participation through other mechanisms, it could consider replacing it with a different type of profit tax. If it decides to retain this equity to reduce tax avoidance risks, it should at least consider adopting a rule for the mining sector that is currently only in the Petroleum Act: that the interest rate on a loan should not exceed the lowest market rate available for such loans.

Even with a more competitive fiscal regime, the government still has work to do to ensure that Tanzania attracts new investment. Investors often care more about policy predictability than the tax level, and developments in the last few years have shaken their confidence in this. For example, the country’s score on the World Bank’s World Governance Indicators of rule of law and regulatory quality has declined since 2015 in absolute terms and relative to other sub-Saharan African countries. Since 2016, an average 73 percent of respondents to the Fraser Institute's annual survey of mining companies have said that Tanzania’s regulatory uncertainty would strongly discourage investment. The Arbitration Act 2020, which largely removes the restriction on using international arbitration to resolve disputes that was introduced in 2017, should ease some concerns. However, the government will need to take additional steps.

The government could clarify some aspects of the 2017 laws. As set out in our initial guidance on these laws, one area in particular need of clarification is what stabilization arrangements are now permissible. These arrangements are now to be based on the “economic equilibrium principle,” as well as needing to be specific, time-bound and provide for periodic renegotiation. Tanzania needs regulations that specify how it will implement these conditions. The government could also improve transparency, starting with meeting its commitment to disclose contracts. This will be critical for improving trust between companies and Tanzanians, and therefore for reducing the likelihood of further regulatory changes in the future.

Taking these steps to improve the investment climate is even more critical now as the ongoing coronavirus pandemic impacts the global economy. The role of gold as a safe haven asset means its price has soared in the first few months of the pandemic. Tanzania’s mining sector has therefore been relatively unscathed so far. However, most other mineral prices have fallen. They are likely to recover to medium-term averages, but it is difficult to know when and they could be particularly volatile over the next few years as economies recover and are reshaped by the pandemic in different ways. As a result, companies may be more cautious in investing in new mines. However, last week’s VAT reform at least allows for cautious optimism that Tanzania can start more fully harnessing its mineral wealth to benefit its citizens.

The model and data used for this analysis are available here.

Thomas Scurfield is Africa economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

- Tanzania’s reintroduction of value added tax refunds for mineral exports better aligns its tax level with other countries, while maintaining a fiscal regime that should still generate significant government revenue.

- This more balanced regime should increase the prospects for new investment, without which the sector and the benefits that it generates will shrink, rather than grow, over the next decade.

- Investment prospects will also critically depend on improvements in policy predictability. Part of this could involve clarifying aspects of 2017 laws and improving transparency.

In 2017, alongside other changes to the fiscal regime and wider laws for the mining sector, the government removed VAT refunds on raw mineral exports. It subsequently interpreted “raw minerals” for this purpose as essentially anything not refined in Tanzania.

VAT is intended as a tax on consumption that the final consumer of a good or service ultimately pays – whether they are based locally or in a foreign country. As part of this system, governments refund companies that pay VAT on inputs during the production process. It is therefore common for countries to provide VAT refunds on mineral exports.

The government’s removal of VAT refunds was likely partly an attempt to incentivize domestic processing. But the economic viability of more processing in Tanzania will vary for different minerals and will depend on both the type of mineral and processing conditions in the country. Few countries are able to fully refine all the minerals that they produce.

Most current and future mines will not have been eligible for VAT refunds, including several projects that are in the pipeline but yet to proceed. Peak Resources’ plan for a rare earth mine involves refining in the United Kingdom, not Tanzania. OreCorp’s prospective gold mine would export doré, which tends to be at least 80 percent pure but is not refined. Jervois Mining’s application for the development of the Kabanga deposit – which has the potential to make Tanzania one of the world’s largest nickel producers – refers to processing concentrates, but not refining.

Investment in new mines is critical. In the most recent year that all of Tanzania’s mines were operating at full capacity, 2016, mining contributed 3 percent of government revenue and 37 percent of exports (this was prior to a recently lifted ban on copper concentrate exports from Barrick’s Bulyanhulu and Buzwagi mines). The country’s large-scale gold mines accounted for 90 percent of this revenue, 90 percent of exports and directly employed nearly 8,000 Tanzanians. But current investment plans for these mines provide for production only up to 2028 (according to S&P Global data). Therefore, without investment to extend these mines’ lives and develop new mines, the sector and the benefits it generates for Tanzania will shrink, rather than grow, over the next decade.

Actual and projected gold production by existing large-scale mines in Tanzania and other regional producers (normalized so 2016 production is 100 for each country)

Source: S&P Global

Until last week’s announcement, the prospects for significant amounts of new investment were very uncertain. As our earlier analysis highlighted, the government was right to increase taxes in 2017. However, its removal of VAT refunds resulted in taxes that were significantly higher than other countries, particularly for less profitable mines. The new regime failed to strike the right balance between generating government revenue and competitiveness.

Our modeling of the fiscal regime for gold and nickel mines shows that the reintroduction of VAT refunds brings the tax level more in line with other countries, while still generating significant government revenue.

Average effective tax rate for large gold mine with gold price of $1,400 per ounce

Average effective tax rate for large nickel mine with nickel price of $17,000 per tonne

Notes: Our calculations in the NRGI mining tax models for Tanzania are published alongside this analysis. We assumed a discount rate of 10 percent. The darker area for the Democratic Republic of Congo shows the tax level when its excess profits tax is not triggered, and the lighter area when its excess profits tax is triggered (with a 25 percent price differential). For Zimbabwe, we assumed that mines operate under an ordinary mining license rather than a special mining license given, that all but one large-scale mine currently does so.

Tanzania could make further improvements. Even with the reintroduction of VAT refunds, Tanzania’s taxes are less responsive to mine profitability than most other regimes that we analyzed. The government could therefore consider a royalty rate that varies with prices. This would provide some relief to mines when prices are low, and capture more revenue for government when prices are high.

The government could also revisit its plan for minority equity in projects. A change here would not be to improve the regime’s competitiveness but rather ensure that the government collects the revenue it expects. As the experiences of Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo show, minority state equity often does not generate government revenue – at least partly because it is more exposed to tax avoidance risks than other taxes. Given the government can achieve the non-fiscal benefits of state participation through other mechanisms, it could consider replacing it with a different type of profit tax. If it decides to retain this equity to reduce tax avoidance risks, it should at least consider adopting a rule for the mining sector that is currently only in the Petroleum Act: that the interest rate on a loan should not exceed the lowest market rate available for such loans.

Even with a more competitive fiscal regime, the government still has work to do to ensure that Tanzania attracts new investment. Investors often care more about policy predictability than the tax level, and developments in the last few years have shaken their confidence in this. For example, the country’s score on the World Bank’s World Governance Indicators of rule of law and regulatory quality has declined since 2015 in absolute terms and relative to other sub-Saharan African countries. Since 2016, an average 73 percent of respondents to the Fraser Institute's annual survey of mining companies have said that Tanzania’s regulatory uncertainty would strongly discourage investment. The Arbitration Act 2020, which largely removes the restriction on using international arbitration to resolve disputes that was introduced in 2017, should ease some concerns. However, the government will need to take additional steps.

The government could clarify some aspects of the 2017 laws. As set out in our initial guidance on these laws, one area in particular need of clarification is what stabilization arrangements are now permissible. These arrangements are now to be based on the “economic equilibrium principle,” as well as needing to be specific, time-bound and provide for periodic renegotiation. Tanzania needs regulations that specify how it will implement these conditions. The government could also improve transparency, starting with meeting its commitment to disclose contracts. This will be critical for improving trust between companies and Tanzanians, and therefore for reducing the likelihood of further regulatory changes in the future.

Taking these steps to improve the investment climate is even more critical now as the ongoing coronavirus pandemic impacts the global economy. The role of gold as a safe haven asset means its price has soared in the first few months of the pandemic. Tanzania’s mining sector has therefore been relatively unscathed so far. However, most other mineral prices have fallen. They are likely to recover to medium-term averages, but it is difficult to know when and they could be particularly volatile over the next few years as economies recover and are reshaped by the pandemic in different ways. As a result, companies may be more cautious in investing in new mines. However, last week’s VAT reform at least allows for cautious optimism that Tanzania can start more fully harnessing its mineral wealth to benefit its citizens.

The model and data used for this analysis are available here.

Thomas Scurfield is Africa economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Authors

Thomas Scurfield

Africa Senior Economic Analyst