A Taxing Question Arises When Commodity Prices Fall

At the end of the last commodity super cycle in the mid-1980s, the future looked bleak for producing countries. The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis suggested that commodity prices would continue falling relative to the price of manufactured goods – which was not good for countries that were selling their resources in order to finance industrial expansion. The consensus around the likelihood of sustained low prices was strong among most experts, including those at the World Bank and IMF. This translated into support for low taxes on extraction companies as a means to incentivize investment, particularly if a country had few other means for obtaining foreign exchange. The result was that throughout the 1990s many countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (including Zambia, Tanzania and Guinea), set low tax regimes.

A few years later, commodity prices started to rise, undoing much of the rationale for the regimes. Given the way resource deals were structured, the rise in prices disproportionately benefited companies rather than countries, which led after some time to a wave of unilateral tax increases and contract renegotiations, often labelled “resource nationalism” by industry analysts.

Fast forward to 2015 and commodity markets are probably undergoing a similar transition into an era of low prices. Prices have slumped: most commodities have lost half of their value since July 2014. Such a sharp decline is not unprecedented. For example, in 2008 prices fell even more precipitously. However, this latest slump appears likely to be longer-lasting, with signs that another “commodity super cycle” has ended. How are governments adapting their tax policies to the “new normal”?

Some governments have already made changes, and companies have seized such opportunities to renegotiate deals where possible. The UK has cut taxes, particularly for companies operating older fields within Great Britain. Mexico has reduced the tax burden on its privatized oil sector, while Argentina has decreased taxes both at central and provincial levels. China has reduced taxes on iron ore, Egypt has reduced to zero its share of profit oil in a large contract with BP, and Iraq is renegotiating its service contracts to reduce the government's exposure to oil prices.

However, many countries have thus far resisted tax cuts. Peru has ruled out tax cuts on mining, in light of the government’s desire to use mining revenues to invest in supporting growth in other sectors of the economy—although it might be compromising on environmental regulations by doing so. Norway is facing a 15 percent fall in investments in its oil industry and (and consequent job reductions) due to the fall in oil prices, but its government has so far resisted reducing taxes.

These different reactions illustrate a tension around the revision of fiscal terms, stemming from two often conflicting tax policy objectives: stability of laws and contracts on the one hand, and flexibility around changing circumstances on the other.

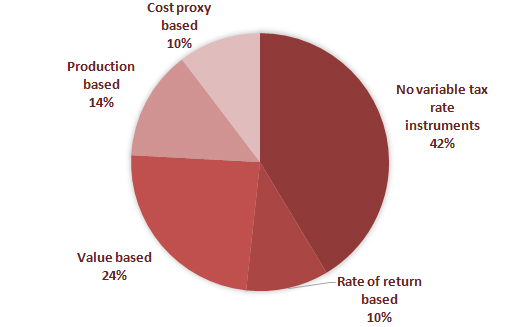

There are ways to maintain policy or contractual stability through changing price environments, with mechanisms such as windfall or super-profit taxes, which adjust the tax burden in response to some market change and so limit the need to alter the fiscal regime itself. Governments have employed a variety of approaches which incorporates rate changes in response to some measure of either return on investments, the market value of production, physical units produced, or a proxy metric for costs such as the depth of an oil well or the number of years a project has been operating. These are what we call here “variable rate taxes.”

Using data collected by the Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment, we’ve made a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the number of petroleum fiscal regimes that use variable rates, shown in the diagram below. There were 29 countries in the sample employing 34 variable rate taxes between them – some countries have two such taxes in their regimes. The majority of countries have some form of tax or fiscal instrument that incorporates a variable rate, a quarter have rates that are directly responsive to changes in commodity prices (i.e., the value of production in the diagram), and a tenth have a tax instrument that is based on some measure of the rate of return made by the taxpayer.

|

Use of variable rates in fiscal instruments in petroleum fiscal regimes |

|

|

|

Source: Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment and authors’ calculations. |

Rate-of-return-based taxes are theoretically the most appealing to both investors and governments as they are the least likely to limit investment decisions. However, they do not appear to be used very often. One reason often given is that they are complex, although this assertion is somewhat questionable: typically these taxes use the same or very similar tax bases as corporate income taxes, so the additional burden on companies and tax administrations is likely to be negligible.

Value-of-production-based taxes provide flexibility around changing prices and are the most common of the variable rate tax regimes. However, these often meet resistance from investors, as attested to by experience of the Zambian government’s attempts to install a variable rate royalty, a reform called the “windfall tax.” The lobbying by companies in Zambia reflected a particular weakness of these types of tax instruments: their rates to differ according to differences in costs and thus may deter investment in high-cost projects, or when prices are low.

Another possible source of resistance among investors is that, in some cases, variable rate tax regimes do not give rise to tax credits for investing companies in their home countries, unlike standard corporate income taxes. This can reduce producer countries’ appeal to companies, and make it more difficult for governments to negotiate such tax regimes.

Rather than prioritizing stability of fiscal laws and contractual terms such as those described above, some governments prioritize continuity of extractive operations, principally because the industry provides crucial jobs and foreign currency. Such objectives sometimes require that governments make tax concessions to companies when the prices of commodities drop. However these type of concessions are difficult to implement not only for governments which lack strong, long-standing relationships with industry, but also because tax policy changes do not uniformly track with price cycles. As Australia discovered, cutting taxes when prices are low can be fairly easy, but increasing them when prices rise can be almost impossible when the full might of the industry lobbyists is brought to bear on the government.

There is no ideal way to provide stability in a volatile economic environment. Both companies and governments have legitimate reasons for calling the other party to the negotiation table at different stages of a project. Rather than sticking to rigid stabilization clauses and hopeful myths about the existence of perfect, untouchable contracts—or going through a sector-wide review at each turn of the market—both governments and companies would be better off acknowledging the need for regular adjustments to contract and fiscal terms, and negotiating legal agreements that provide such flexibility.

Politicians who dream of billion dollar investments, from West Africa to Indonesia, are feeling the pressure to cut taxes. We recommend that they take a look at the obverse side of the coin before rushing to the negotiation table. One of the most immediate consequences of the crash in prices has been the industry’s drive to cut costs, after years of cost inflation during the boom. This means that the actual impact of the price crash on their profitability may not be as large as the price decrease itself, although the consequences may be felt with some delay while the industry finds solutions to its belt-tightening challenges. Indeed, a recent study from the University of Oxford shows that for every one percent decrease in the oil price in one year, oil companies’ costs decreased by 0.5 percent the next year.

Resource companies have already postponed or cut $100 billion in investments. But as previous commodity cycles have shown, these leaner times will not last. Therefore if government officials decide to give tax breaks to projects in economic distress, they should be careful in limiting these breaks in time and scope, in order to restore a progressive fiscal regime when prices rise.

Companies and their host governments must address the immediate issue of declining profitability and investments. But the silver lining is that any new renegotiation of fiscal terms could be an opportunity to craft better tax regimes and mechanisms for absorbing volatility. These would allow the industry to withstand the current drop in prices while ensuring a fair split of revenues, and preventing disputes in the future.

Thomas Lassourd and David Manley are economic analysts at the Natural Resource Governance Institute.

Watch experts from around the world discuss these issues on 26 June at the NRGI conference in Oxford.

We would like to thank Salli Swartz of Artus Wise Partners for her helpful comments on this article.

Authors

David Manley

Lead Economic Analyst – Energy Transition