Three Proposals for Mineral-Dependent Countries During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Coronavirus containment measures have hit economies hard—and with them, government revenues. Most natural resource-dependent countries are experiencing a double shock as their main source of foreign currency has crashed along with fiscal revenues. The situation is most severe in oil-dependent countries; oil prices have declined by more than 60 percent on average since the start of the year, and occasionally dropped below $0 a barrel. Mineral-dependent countries have been affected too, but in more surprising ways.

Gold and uranium prices have climbed, driven by a combination of safe-haven buying and production cuts. As one senior mining official from a gold-producing country said on a webinar recently, “[The companies] are making money!” Governments dependent on these minerals, such as in Burkina Faso, Guyana, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Niger and Suriname, will be able to offset some of the revenue lost in other sectors through increased mining receipts. How much of a buffer gold or uranium revenues will provide depends largely on these countries’ fiscal terms and how well they negotiated their mining contracts to integrate a progressive tax regime to take advantage of more profitable periods.

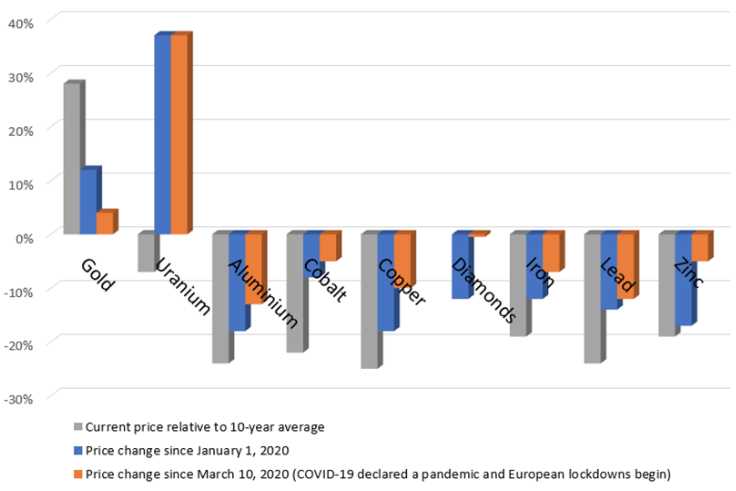

However, prices of the other most widely traded minerals have collapsed by 8 to 18 percent since the start of the year. While there was a slight recovery in April, in general prices remain low by historical standards but unpredictable.

Selected mineral price changes since coronavirus outbreak (spot markets as of late April)

Sources: London Metals Exchange; Ziminsky Global Rough Diamond Price Index; Trading Economics

Sources: London Metals Exchange; Ziminsky Global Rough Diamond Price Index; Trading Economics

Mine shutdowns are, in some cases, doing worse damage to public finances than low prices. Production is being cut as mines suspend operations or reduce output to prevent spread of the virus, even where prices are high enough keep a mine profitable. For instance, Peru’s enormous Antamina copper and zinc mine is being suspended to contain the outbreak. Mexico has suspended production at all mines. Malaysia and Mozambique suspended their bauxite mines. South Africa has reduced mining production by 50 percent following a full shutdown. Further disruptions, whether to prevent the spread of the virus or in response to infections at mine sites, are likely, despite some governments’ efforts to keep production going by declaring mining an essential service.

Shutdowns and weak prices are hitting certain countries harder than others. In 2016, 27 percent of Guinea’s fiscal revenues, 26 percent of Zambia’s and 24 percent of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) were paid by mining companies. Even these high numbers underestimate the governments’ dependence on the mining sector, as they do not include income taxes from mine workers and taxes from mine suppliers. The longer the containment measures persist, pushing down demand and increasing stockpiles, the greater the pain for mineral producers will be.

Still, the main worry for many mineral-dependent countries is not just the decline in fiscal revenues. Rather, it is that many will face balance-of-payments crises, meaning they will not have enough foreign currency to pay for imports or service external debts. Mineral exports are the primary source of foreign currency for more than 20 countries, including Eritrea, Mongolia and Tajikistan.

In a handful of countries with small foreign reserve buffers and limited access to foreign capital, sovereign debt crises may coincide with balance-of-payments crises. As the export dependence, foreign reserve and credit default swap (CDS) spread (an indicator default probability) figures in the table below indicate, several African countries, including DRC, Guinea, Mauritania, Sierra Leone and Zambia, are at high risk of these dual crises.

Mineral-dependent countries’ risk of sovereign debt and balance-of-payments crises

| Country | Main mineral exports | Mineral exports as a percentage of total exports (2017 or most recent) | Risk of debt distress (based on CDS spreads, IMF DSAs and govt reports) | CDS spread on sovereign debt (as of April 1, 2020) | Reserves by months of imports (2018 or most recent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Iron, coal, gold | 62% | Low | 0.0% | 2 |

| Bolivia | Zinc, gold, lead | 49% | Low | 6.7% | 8 |

| Botswana | Diamonds | 91% | Low | 1.3% | 9 |

| Chile | Copper | 56% | Low | 1.0% | 4 |

| Namibia | Diamonds, copper | 61% | Low | 4.5% | 4 |

| Peru | Copper, gold, zinc | 63% | Low | 1.8% | 11 |

| South Africa | Gold, diamonds, platinum, iron | 60% | Low | 3.7% | 5 |

| Tanzania | Gold | 43% | Low | 6.7% | 6 |

| Burkina Faso | Gold | 85% | Moderate | 8.2% | - |

| Ghana | Gold | 53% | Moderate | 9.6% | 3 |

| Guyana | Gold, aluminum | 51% | Moderate | 9.7% | 2 |

| Kyrgyzstan | Gold | 57% | Moderate | 8.2% | 4 |

| Mali | Gold | 63% | Moderate | 9.7% | - |

| Mongolia | Copper, coal | 91% | Moderate | 9.7% | 4 |

| Niger | Uranium | 60% | Moderate | 9.7% | - |

| Papua New Guinea | Gold, copper | 45% | Moderate | 8.2% | 4 |

| Suriname | Gold | 80% | Moderate | 8.2% | 3 |

| Tajikistan | Aluminum, gold, zinc, lead | 78% | Moderate | 9.7% | 4 |

| Congo, DR of | Cobalt, copper | 90% | High | 11.1% | 0 |

| Eritrea | Zinc, copper | 97% | High | n/a | 1 |

| Guinea | Aluminum, gold | 81% | High | 14.8% | 3 |

| Mauritania | Iron, gold, copper | 53% | High | n/a | 3 |

| Mozambique | Coal, aluminum | 69% | High | 13.4% | 4 |

| Nauru | Phosphates | 74% | High | n/a | 4 |

| Sierra Leone | Iron, titanium, diamonds | 67% | High | 14.8% | 3 |

| Zambia | Copper | 84% | High | 15.00% | 2 |

What can officials do, bearing in mind that each country faces its own challenges and no single policy would be applicable in every context?

1. Support mine workers and foreign exchange generation rather than shareholders

The mining sector produces fewer jobs per dollar of revenue generated and has smaller economic spillovers than almost any sector. But mining is a major employer in some countries and localities. In many countries, it is also an important generator of much-needed foreign currency.

Authorities should design financial relief measures for mines to meet specific policy goals, and only apply them to mining projects that are suffering from historically low commodity prices. If the goal is to keep workers employed, it is better for governments to pay a portion of workers’ salaries as long as they are kept on the payroll or defer payroll taxes, rather than bail out companies and their shareholders. If the goal is to maintain operations, governments can provide logistical support to mines, for instance through virus testing and keeping key trade routes open.

2. Resist impulsive tax relief and subsidy measures

Mineral prices are likely to trend toward their medium-term averages, though it is difficult to know when, given global uncertainty around demand and coronavirus containment. In the meantime, mining companies, employees and business associations are pressuring officials for tax relief and subsidies as compensation for shutdowns, sometimes successfully.

There are serious risks associated with renegotiating mining contracts or changing tax regimes in a manner that fails to capture future profit increases. Past experience shows that governments often fail to cancel tax relief after prices have risen again. Further, asset owners are in weak negotiating positions when prices are low.

Introducing sliding royalties might be one approach to providing temporary relief while automatically responding to a price rise. Sliding royalty rates automatically fall when prices fall, providing some relief in the current context, and rise when prices recover.

3. Distinguish between public sector liquidity and solvency crises

In some mineral-dependent countries, the drop in fiscal revenues will generate significant burdens on public finances. Many governments will need to further indebt themselves to overcome a temporary shock to fiscal revenues. However, in a handful of countries, the twin shocks are likely to push them over the edge into insolvency.

Countries in liquidity crises must find sources of financing to withstand the next couple of years. While the G20 have offered support, more will be needed. Temporary debt relief is part of the solution. Additional borrowing from institutional investors and the central bank may also be necessary. Debt monetization is an option worth considering during a contractionary spiral, especially in countries with shallow financial sectors and limited access to international capital, but with adequate foreign reserves to prevent a major depreciation. Where governments are insolvent, debts must be restructured immediately to create the fiscal space to respond to the coronavirus crisis and set themselves up for growth once the crisis is over.

Andrew Bauer is a consultant to the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).