Uganda’s Local Governments Need Clarity on Oil Revenue Sharing

Driving from Hoima to the breathtaking banks of Lake Albert, where Uganda’s long-awaited 1.4 billion barrel oil project is located, it is clear that the government has been preparing for production for years. New roads and bridges criss-cross the region. However, one area in which the government is unprepared is the sharing of oil royalties with the region’s districts.

Section 75 of the Public Financial Management Act 2015 (PFMA) provides for the sharing of royalty revenues with local governments, and cultural or traditional institutions named in the government gazette. But the law is vague about the precise sharing mechanism. The challenges that this is causing for districts in the oil-rich region were apparent in a workshop that NRGI held with civil society organizations there earlier this month: scarcity of details has frustrated local officials’ planning and their management of public expectations. With production likely to start in just three years, the national government is running out of time to address these challenges.

Providing clarity to subnational authorities is all the more important given the uncertainty that the energy transition has created around estimates of the total royalties that the Ugandan government will receive. Local governments and cultural and traditional institutions don’t have a sense of how much funding they can anticipate. The speed of the world’s shift away from oil will impact the price that the Lake Albert oil commands, as well as the potential for subsequent oil projects in the country.

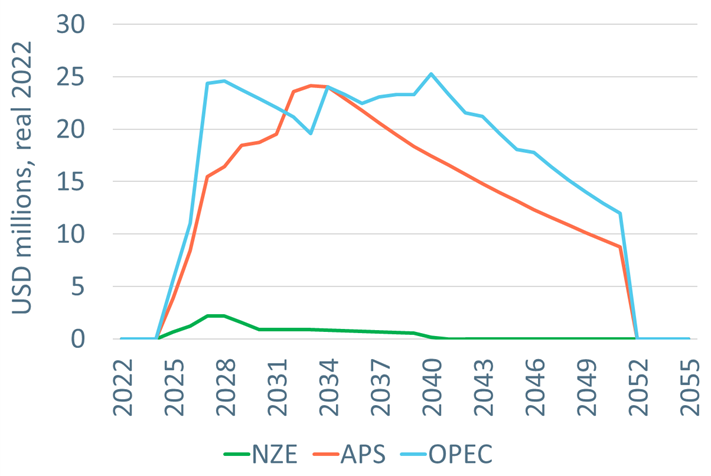

To bring some of that much needed clarity, we developed a simple model which helps subnational entities assess how much revenue they might receive. The chart below shows the possible local government share from the Lake Albert project in three global demand scenarios, based on our modeling. The Announced Pledges Scenario (APS) from the International Energy Agency (IEA) assumes that countries implement the climate commitments that they have made to date. The reference scenario of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) envisages a slower transition, while the IEA’s Net Zero (NZE) scenario assumes that the world manages to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and therefore sets out a much faster transition. (All of these scenarios have been updated by Rystad Energy to reflect developments since they were generated and converted to implied prices.)

Local government share of royalty across possible price scenarios

Local government revenues differ significantly between these three scenarios. In the OPEC scenario, Uganda’s local governments could receive around $20 million a year on average. As our model shows, this amount is more than double the revenues that districts in the region were expected to raise through normal, non-oil means in 2021/22 (using the initial list of districts that would receive a share). In the NZE scenario, the local government share of oil revenues would be much less, possibly around $0.6 million. Though even this smaller amount could be significant for some individual districts if managed carefully.

How revenues will be shared between individual subnational entities is currently unclear, however. As our model highlights, the gaps in detail about the sharing mechanism make this assessment impossible.

Uganda’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development and Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development can clarify the situation by answering four key questions:

Which districts and cultural or traditional institutions will receive a royalty share?

The law states that six percent of total royalty revenues will be shared among the local governments “located within the petroleum exploration and production areas.” How these areas will be defined is unclear. An early version of the public financial management bill specifying districts that will receive a share (including some districts which are not home to any granted petroleum licenses) has confused this issue further. This list was retracted in 2015, but another list is yet to be published by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development. One percentage point of the royalty due to the central government will also be shared with “gazetted cultural or traditional institutions.” However, which institutions will be gazetted is similarly unclear.

What criteria will be used to create the sharing formula, and how are they defined and weighted?

Fifty percent of the local government share will be divided among local governments involved in production based on their production level or “impact,” according to section 75 of the PFMA. The other 50 percent will be shared among all local governments based on “population size, geographical area and terrain.” However, the formulas in the law’s schedule 6 only include production level and population size. Clarity is therefore needed from the government on whether the criteria in section 75 or the criteria in schedule 6 will be used, how each criterion is defined and, if the formulas are to contain more than one criterion, how the different criteria will be weighted. For example, the first fifty percent will likely be divided between five districts if production level is the only criterion, but it could be divided between a lot more districts if impact is also included depending on how it is defined. For example, if all the districts through which the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline runs are seen as impacted.

What share will cultural or traditional institutions receive?

The amount that “one percentage point of the royalty due to the central government” entails isn’t clearly defined. For example, if the total royalty revenue is USD 100 million in a given year, the central government will initially receive $94 million (with the remaining $6 million being shared among local governments). Whether cultural or traditional institutions will receive $1 million (representing 1 percent of total royalty revenue) or $0.94 million (representing 1 percent of the royalty revenue received by central government) is not clear.

What are the rules governing how subnational entities manage revenues?

The PFMA earmarks local governments’ royalty revenues for “development purposes.” However, there is a risk that local governments could apply a broad definition to development purposes and, as a result, won’t spend petroleum revenues as intended. There is no instruction in the PFMA for how cultural and traditional institutions should spend their share of royalty revenues nor for what happens to royalty revenues that are unspent by recipient entities. Section 17 prevents local governments from retaining a budget allocation after the end of a given financial year. However, providing access to leftover oil funds in subsequent years will be important so that local governments don’t spend money ineffectively to avoid losing it. This will also prevent them from smoothing spending as royalty revenues fluctuate with production and prices.

The challenge of establishing an extractives revenue sharing mechanism that benefits communities is not unique to Uganda. NRGI’s work in countries such as Indonesia highlights the difficulty in ensuring revenues are shared based on a clear and predictable formula that is broadly seen as fair. Such complexities have led to delayed implementation in several countries, such as Guinea, reinforcing the need for the Ugandan government to start focusing on this issue now.

And establishing the mechanism is only the first step. As the past experience of Peru highlights, even if Uganda strengthens its rules for managing subnational revenues, increasing the capacity of local governments to address the unique challenges of resource revenues will be critical. Similarly, Colombia provides lessons on the importance of developing transparent processes for both the distribution and use of funds.

Uganda therefore has significant work to do to ensure that revenue-sharing will benefit communities in the oil-producing region. But until the central government addresses the four gaps outlined above and provides clarity on the revenue sharing mechanism, local governments and communities will be making plans based on guesswork.

Authors

Thomas Scurfield

Africa Senior Economic Analyst

Paul Bagabo

Senior Officer