Water Management, Environmental Impacts and Peru’s Mining Conflicts

On 14 October 2016 a confrontation between Peruvian police and peasant communities protesting the beginning of the Las Bambas copper mine extractive operations, ended with one protester killed by police fire. Quintino Cereceda Huiza was the fifth local resident in 13 months to die at Las Bambas in civil unrest. Four others were killed by police fire in September 2015, when the first of these protests erupted.

The police intervention was denounced by the Interior Minister Carlos Basombrio as one that had not been planned nor ordered by the ministry or the police national leadership, but by local police officials. Because mining companies contract police officers to provide security at mining sites, there are suspicions that the Sino-Australian mining company MMG may have played a role in the fatal intervention. The public outcry around this matter will hopefully lead to the revision or even the elimination of these kinds of arrangements.

The protests in the Las Bambas area signal profound shortcomings in mining governance in Peru, particularly with respect to the way the national mining sector authorities handle and approve changes in mining project design and environmental impact assessments (EIAs).

When the Las Bambas project was owned by the Swiss company Xstrata, the plan was for the copper to be processed in a mill located in another province and the metal was to be transported there by a slurry pipeline. But since MMG bought the project from Xstrata in 2014, the new design includes a mill located in the district’s capital Chalhuahuacho, and overland transportation of the extracted metal to the coast, with significant environmental impacts (and approval by Ministry of Energy and Mines of this new design has in turn has sparked massive social protests against a project that previously had met no significant social opposition.

As has been reported by CONVOCA, the issue here is that new legislation designed to expedite the approval of new investment projects allows national authorities to approve changes in pre-existing EIAs without informing (much less consulting with) local authorities and local populations.

In the meantime, in the regions of Cajamarca and Cusco, conflicts between local rural populations and mining companies continue. At the core is the fear that mining will destroy, deplete and/or pollute water sources and waterways. And there are good reasons for such fears, as mining is one of the main contributors to the pollution of waterways in Peru.

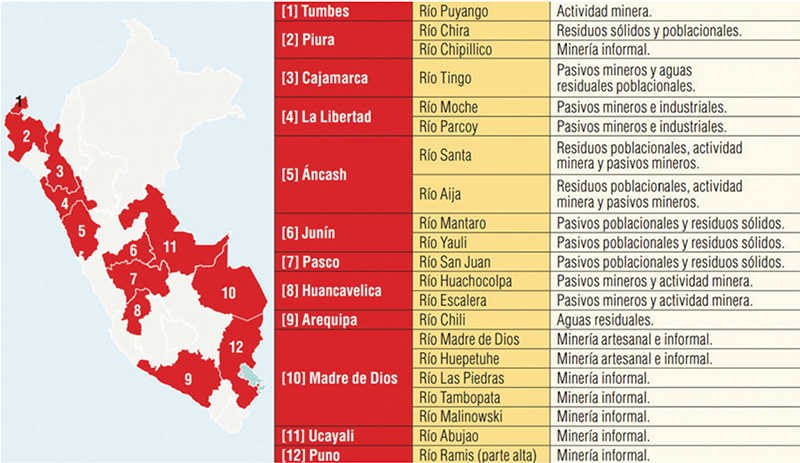

The 15 most polluted rivers in PeruSource: Cooperaccion

A recent report by Peruvian NGO Cooperaccion on water rights in Peru reviews relevant national legislation and institutional arrangements, and uses as case studies the Rio Grande (Cajamarca) and Cañipaco and Salado (Cusco) watersheds.

The findings are troubling:

- The allocation of water rights by the National Water Authority (Autoridad Nacional del Agua – ANA) is opaque.

- The state uses information regarding watershed water availability that is more than 20 years old and is only now being updated.

- As glaciers recede and water cycles become unsteady, there is hydric stress in areas where mining and the resulting demand for water is expanding.

- Local water management offices are extremely weak in face of powerful private large-scale mining projects; information and analysis regarding water in EIAs in insufficient.

Nevertheless, the scarce information made available so far by the ANA indicates that—despite the relatively low consumption of water by mining operations (1.3 percent of total water consumption in Peru)—in certain watersheds mining actually consumes quite significant portions of the available water. This is because the denominator in that national figure is all water available, including the Amazon basin, which holds 95 percent of Peru’s water. If one looks at the figures on a basin-specific approach, the picture is quite different.

Water rights by watersheds allocated by ANA

Source: Cooperaccion

In Cajamarca, a history of negative impacts on water supplies has been the source of longstanding conflicts between local populations and a Yanacocha-owned mining project in the Rio Grande basin. Similar distrust has led local rural populations in the Celendin and Bambamarca provinces to reject and paralyze the new Conga project, also owned by Yanacocha. In Espinar, local people and authorities blame the Tintaya mining project for the contamination of the watersheds, and the associated negative impacts on the health of the population, cattle herds and the land.

National mining and water authorities as well as legislators should discuss and address these findings. Reforms are imperative. ANA must generate and make available the information regarding allocated water rights on a basin-by-basin and year-by-year basis. There is no reason why, in a time when Peruvians can access information regarding territorial concessions, they cannot see the associated documentation on hydrological impacts. Making this information available in the form of a public water cadaster should be part of Peru’s Open Government Partnership commitments. And the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative should mandate disclosure of this information just as it now requires reporting on territorial concessions for oil, gas and mineral production.

Citizens also need more information regarding the availability of water at the basin level, especially those basins impacted by global warming.

Finally, the national government should strengthen agencies like ANA and also instruments like the EIAs to overcome the power and information asymmetries vis-à-vis mining companies and to assess the full impact of mining activities on the availability and quality of water for all users in watersheds.

The findings of research by both CONVOCA and Cooperaccion shed light on mining governance shortcomings around these two issues which are at the core of most of the “socio-environmental” conflicts that arise between local populations and mining companies. All interested parties should address these issues in order to reconcile extractive activities with sustainable development in resource-rich territories.

Carlos Monge is the Latin America director at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

NRGI has provided grants to both CONVOCA and Cooperaccion.