What Ghana’s 2021 Budget Reveals About Its Oil Fund Management

Ghana’s 2021 budget, titled Economic Revitalization through Completion, Consolidation and Continuity, was widely anticipated. Ghanaians hoped that the budget would include steps to address both the immense challenges brought on by the coronavirus pandemic and low revenues resulting from a downturn in crude oil prices. Revenue shortfall amounted to GH₵13.6 billion while expenditures rose by an estimated GH₵11.7 billion in 2020; this has led to more uncertainty about the future of Ghana’s recovery plans.

In addition, as in many other African economies, debt also threatens the projected economic recovery in Ghana, something the government has acknowledged in the 2021 budget.

Commodities are expected to play an important role in addressing Ghana’s debt challenges. Petroleum exports will likely decline in the medium term , from a peak of 71 million barrels in 2019 to about 59 million barrels in 2024, and so will revenues. Though crude oil prices have recovered from the depths of the second quarter of 2020, there is no guarantee that these will be sustained, thus limiting the role of petroleum revenues in addressing Ghana’s debt burden. Nonetheless, petroleum is still an important source of revenue and a likely part of the solution to Ghana’s public financial challenges.

Unresolved governance issues

Despite the 2021 budget’s attempt to address concerns around petroleum revenue spending in Ghana, it fails to address key governance questions around what will happen to unspent revenue and what constitutes public investment, among other issues.

Allocation for public investment

Public investment is generally understood to be spending on assets or infrastructure with long lifespans. But the lack of a clear explanation of Ghana’s public investment expenditures has over time led to various approaches by the Ministry of Finance on where to allocate the funds, leading to disagreements among different stakeholders. For example, between 2011 and 2016, 70 percent of oil revenue designated for budget support (the Annual Budget Funding Amount, or ABFA) was allocated to capital spending, which includes roads, agriculture, education and health infrastructure, against 30 percent allocated to recurrent expenditure, which typically covers payments for services and supplies. The Petroleum Revenue Management Act (PRMA) Section 21(4) states: "For any financial year, a minimum of seventy percent of the Annual Budget Funding Amount shall be used for public investment expenditures consistent with the long-term national development plan or with subsection (3)."

In 2017, the government prioritized spending of oil revenues on “physical infrastructure and service delivery in education,” in line with the PRMA. Civil society organizations raised concerns about whether this spending was consistent with the Ministry of Finance’s previous interpretation, which had restricted public investment expenditure to capital spending Between 2017 and 2019, recurrent expenditure on the Free Senior High School Program, which included the payment of fees and supplies, represented an average of 52 percent of ABFA. The Public Interest and Accountability Committee (PIAC) called on the government on numerous occasions to adhere to the Ministry of Finance’s previous interpretation of the PRMA but the government argued that investment in education qualifies as public investment expenditure and that is not entirely synonymous with capital expenditure, with an explanation included in the 2021 budget.

This changing interpretation of “public investment expenditure” has led to recurrent expenditures for which volatile petroleum revenues are ill-suited. Previous NRGI research has emphasized the challenges with spending volatile resource revenues on recurrent expenditure. There is broad consensus that public investment in key sectors can enhance growth. Ghana’s government should clarify the definition of public investment expenditure to refer to only non-recurrent expenditure in the PRMA Regulations (L.I. 2381) or in a PRMA amendment. This would also encourage consistent implementation of the rule by future ministers of finance.

Unspent petroleum revenues at the end of the year

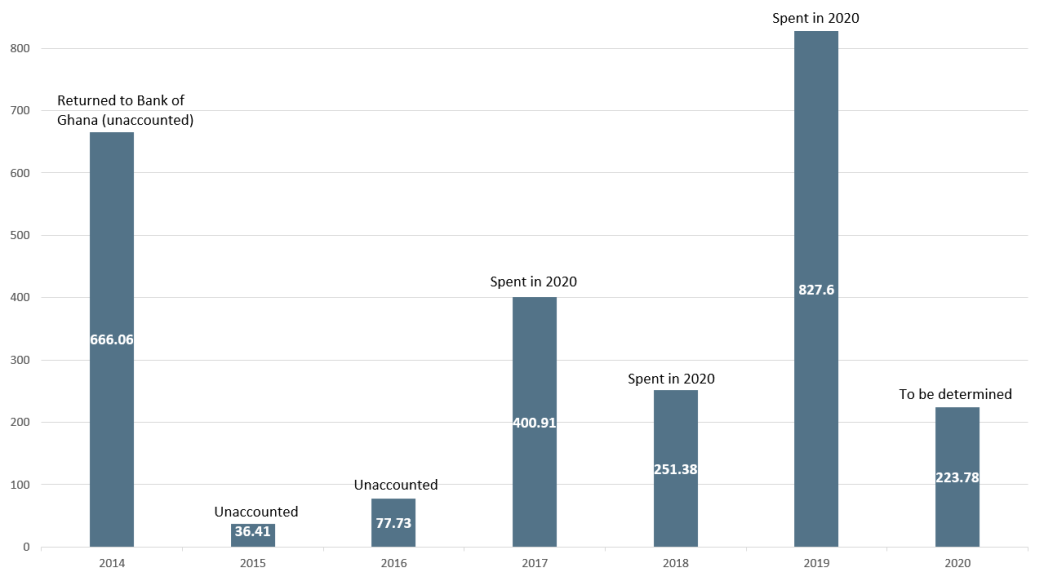

The use of unspent petroleum revenues at the end of the budget year is another unsolved issue. Successive governments have managed unspent ABFA differently since this first came up in 2014. That year a total of USD 222.93 million (GH₵666.06 million) of ABFA was unspent. The amount, according to the Ministry of Finance, was returned to the Bank of Ghana at the end of that year as the bank assessed the government’s financial position. However, in 2015, the Ministry of Finance did not disclose of how it applied a balance of GH₵36.41 million. The following year’s Ministry of Finance reconciliation report made no mention of the unused balance, as it should have. Similarly, the Ministry did not account for the unused balance of GH₵77.73 million at the end of 2016 in its report to the parliament.

Treatment of Unused ABFA, (2014-2020) (GH₵ millions)

Click to enlarge

Source: Ghana Ministry of Finance (Reconciliation Reports, 2014-2016; 2021 Budget Statement)

In 2020, the Ministry of Finance brought forward and spent unused ABFA from 2017-2019 (amounting to GH₵1.48 billion; see figure above) alongside allocations for 2020. Since 2018, the PIAC and other civil society actors have called upon Ghana’s government to provide details of the unspent revenues; these calls only elicited a public response in the heat of the campaign leading up to the December 2020 elections. According to the ministry, the combined 2017 and 2018 amount of GH₵652.29 million was transferred to the Road Fund while 2019’s GH₵827.60 million was used to meet the 2020 ABFA shortfall due to the pandemic. It is unclear which provisions, if any, in the PRMA support the transfer of unspent ABFA into the Road Fund or to meet ABFA shortfalls in subsequent years. Also unclear is which year’s appropriation (budget)—which provides the legal authorization to spend based on agreed activities—covered the spending of these unused revenues.

Additional challenges to the financial management of Ghana’s public sector include delays in the contracting process for projects, disbursement of funds and contract execution. Issues related to unspent ABFA will continue unless these challenges are resolved. Dialogue and consensus building among stakeholders on how to treat unspent funds in the future would avoid various conflicting interpretations arising between provisions in the Public Financial Management Act and the PRMA.

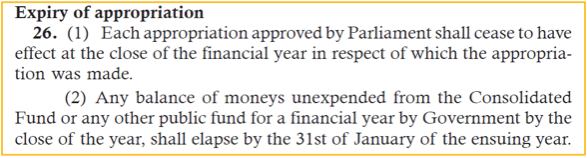

While the PRMA does not prescribe how unused ABFA at the end of the year should be treated, Section 21(1) provides that it must be part of the national budget and subject to same budgetary processes, bringing the ABFA under the public financial management rules in terms of management and accounting. And Section 26 of the Public Financial Management Act states clearly that such appropriations lapse by the end of the first month of the following year, meaning that the government needs a new appropriation from the parliament to use these funds.

Section 26 of the Public Financial Management Act, 2016

Inability to spend within the appropriation period, for whatever reason, creates public financial management complications in terms of unspent balances, re-budgeting and project execution. With petroleum funds, unspent funds make tracking and accounting for revenues within the framework of the PRMA provisions difficult.

Ghana’s government must urgently tackle the underlying issues of public financial management and delays in projects on which the money is spent. In addition, stakeholders (the Ministry of Finance and ministries that receive ABFA; oversight bodies like PIAC and Ghana EITI; and civil society actors) must engage in order to answer the following questions and possibly factor them into future amendments of the PRMA:

- What should happen to unused ABFA and where should these unused funds be saved?

- Should new appropriation in accordance with the Public Financial Management Act allow for a change in projects and programs earmarked in a previous appropriation?

- Does government ringfence ABFA funds, and if not, should they?

Discretionary capping of the Ghana Stabilization Fund

The Petroleum Revenue Management Regulations (L.I. 2381), passed in 2019, sought to address the situation where the minister of finance sets a discretionary cap on the Ghana Stabilization Fund by defining a formula for setting the cap. Regulation 8(1) states “In pursuance of Section 23 of the Act, the Minister shall, in recommending the maximum amount of accumulated resources in the Ghana Stabilisation Fund, ensure that the amount is not less than the average Annual Budget Funding Amount over a three year period.” While this provides guidance for setting a maximum balance on the fund, no minimum amount is specified; this could leave little money in the fund for its stated purpose of addressing revenue volatilities or debt. Though the 2021 budget did not propose a cap, the implementation of L.I. 2381 will mean that the Ghana Stabilization Fund would likely not grow beyond USD 400 million in the medium term (based on petroleum revenue projections in the 2021 budget). While a lower ceiling on the Ghana Stabilization Fund would make funds available for real-time debt servicing, it reduces the opportunity for government to rely on the fund to address shocks to the economy, fund future budgets and service future debt.

Ways forward

Resource revenues and good public financial management have the potential to help address Ghana’s financing and borrowing needs, and its economic recovery plans. To ensure this potential is realized:

- The government should adhere to the generally accepted interpretation of public investment as referring to non-recurrent spending, and clarify this in the Petroleum Revenue Management Regulations (L.I. 2381) to avoid using volatile revenue streams for recurrent expenditures.

- The Ministry of Finance should initiate consultations on an amendment of the PRM regulations that would provide clarity on how government should manage unspent revenues.

- The government should undertake a review of the capping mechanism of the stabilization fund.

Denis Gyeyir is an Accra-based Africa program officer with the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Authors

Denis Gyeyir

Africa Senior Program Officer