Algeria Needs Fresh Thinking More Than Its Oil Projects Need Tax Breaks

العربية »

Algeria, one the biggest oil and gas producers in North Africa, was already facing serious economic challenges before the coronavirus pandemic hit. The country needed a minimum price per barrel of USD 92 in order to match expenditure and balance its budget in 2020. Even before the sharp oil price drop at the start of the year, this “fiscal breakeven” price was untenable, since Algeria’s budget deficit was 9.2 percent of GDP in 2019 and expected to be 10.4 percent in 2020.

The pandemic hit, and the price of oil dropped from $60 a barrel in December 2019 to just $20 a barrel in April 2020, before between $40 and $43, where it sits now. Though most oil and gas producers were left reeling from the price drop, Algeria’s situation was compounded by its new government’s fragile political position following the ousting of the Bouteflika regime in 2019.

Photo ID: DS-MA093 World Bank

Photo ID: DS-MA093 World Bank

With no savings left in the country’s oil stabilization fund, Algerian officials had no choice but to cut spending; but the newly installed government did not want to pull back on promised reforms. As the oil price tumbled, the government announced spending cuts on goods and services, while leaving wages, pensions, health and education-related spending untouched. In addition, the government asked Sonatrach, the national oil company, to halve its operational and capital expenditures, and to freeze most new projects, such as petrochemical plans, refineries, new drilling and maintenance.

However, these measures will not solve Algeria’s economic problems, in the short or long terms. Despite the current low oil price, the government still views oil and gas production as key to the country’s economic future. For example, the government may re-invest in its Libyan oil fields since it became possible to restart production. In addition, Sonatrach is planning to expand and diversify its gas export portfolio.

Algeria also has several potential oil and gas developments in its own territory. However, many of these are not currently economically viable. In an effort to make them viable, the discussion usually turns to the taxes companies pay. Since the taxes and royalties companies make to governments are often larger than project operating costs, there is pressure on governments to reduce taxes. Governments such as Algeria must identify which projects would become viable with lower taxes, and which do not need a tax break.

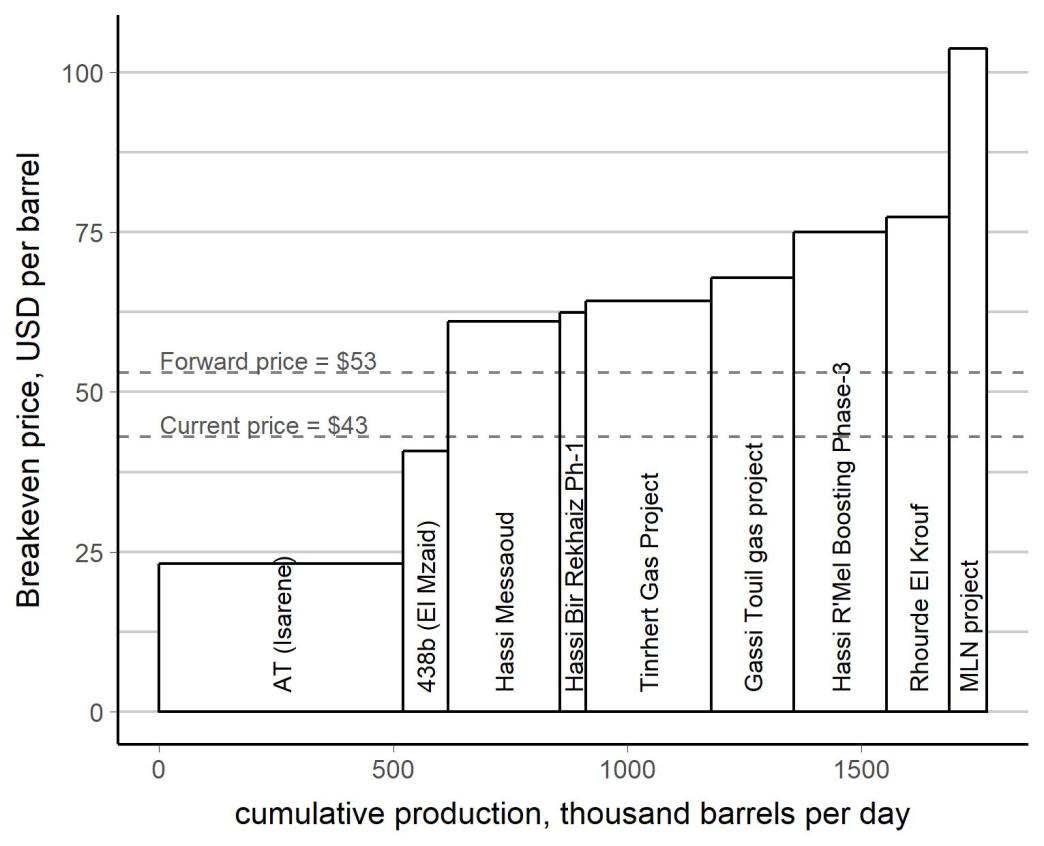

In a new briefing, “A Race to the Bottom and Back to the Top: Taxing Oil and Gas During and After the Pandemic,” my NRGI colleagues highlight the risks faced by oil and gas producers when seeking to catalyze production with tax breaks. The report, which uses data from energy experts Rystad, highlights the challenges faced by Algeria with its discovered but underdeveloped fields. The cost curve in the figure below shows the break-even prices and the expected daily production levels for the oil and gas projects that Rystad Energy analysts expects to be developed over the next five years.

Projects furthest to the left have the lowest costs. A government official in Algeria might expect those to be safe as investors will not require tax breaks to make the projects breakeven. Those projects furthest to the right—with the highest costs of production—are in much greater danger of being postponed or even cancelled. Only a large tax break would make these appealing to investors. The tax breaks required for these projects could be so large that the government could conclude it is not worthwhile, given they would generate little government revenue.

Government officials may be most tempted to offer tax breaks to the projects in the middle of the cost curve, as a small change in taxation could make an otherwise unviable project viable. However, offering tax breaks to companies in order to catalyze new production is a high-risk strategy for Algeria.

The government must not only to evaluate tax rates in the short term, but to consider the future, when oil demand will decrease and prices are expected to stay low. Algeria could provide tax breaks to help get the projects developed, but it is important to remove these tax breaks if prices and profits rise again. Using sunset clauses which ensure tax breaks are only active when needed may help. But better still would be a progressive tax regime that responds automatically to changes in profits.

Algeria needs revenues from the oil and gas sector, and cannot afford to delay projects. The local demand for energy is also increasing, and Algeria could face a crisis in which the country needs to buy gas for internal consumption. Moreover, since the 2014 oil price crisis, the government has been unable to save money in its sovereign wealth fund or to meet growing social demands for access to energy.

Globally, the pandemic is devastating economies, but it is also expedited the much-needed global transition to renewables. For the new government, this will be a pivotal moment to bring Algeria out of this crisis and prepare for the global energy transition.

Algeria’s new leadership must consider the long-term sustainability of the Algerian economy, and encourage investments in renewable energy to meet the country’s growing domestic energy needs. Not only will developing a renewable sector help to diversify the economy, it could also free up for export gas supplies currently consumed locally. This could generate the revenue needed to further diversify the economy, and ultimately end the country’s unsustainable dependency on oil and gas.

Laury Haytayan is the Middle East and North Africa director at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Authors

Laury Haytayan

Middle East and North Africa Director