Tullow Pulls Back the Curtain

Tullow, the Anglo-Irish oil company that works mostly in Africa, voluntarily disclosed detailed information about the $1.5 billion it paid to governments in 2012 and 2013. Appearing in its 2013 Annual Report, the data is broken down by payment type (taxes, royalties, etc.) for each of Tullow’s projects, located in 22 countries.

Now, why is this so exciting?

As noted by the Financial Times and several NGOs, Tullow’s disclosures are exactly the type of transparency that many oil companies have been resisting with all their might. The American Petroleum Institute, the oil industry lobbying group, sued the US Securities and Exchange Commission in an attempt to avoid disclosing project-level payments to governments around the world. API members are also maneuvering behind the scenes to slow the spread of this reporting in the EU and other jurisdictions. Despite these efforts, in 2013, the EU decided to require project-level reporting by oil and mining companies, and EU member states are now putting in place national laws that incorporate this new standard. Tullow chose to implement the new standard in advance of these forthcoming legal requirements.

Along with showing the feasibility of project-level reporting, the Tullow disclosures illustrate its usefulness. In relatively transparent countries, like Ghana, the Tullow report illustrates how project-level reporting complements data from other sources. For instance, companies can provide information that is more current than the data contained in Ghana’s EITI reports, publications that are useful but often produced with a significant time lag.

Project-level reporting also complements contract disclosure. The contracts between Tullow and the Ghanaian government are available online, and they help to explain why Tullow paid what it did in 2013. The contracts set out the tax rates and incentives that led Tullow to pay Ghana $107 million in income taxes last year. The contracts also set out the royalty obligations, which Tullow appears to have paid as part of its 812,000 barrel in-kind payment to the government, as no dollar royalty payments are reported. This is valuable insight for oversight actors who then can monitor how the national oil company manages this oil, valued at around $85 million.

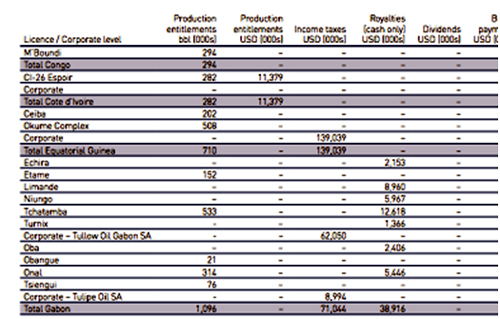

Tullow’s report sheds light on more opaque environments too. Equatorial Guinea and Gabon are the only two countries to have been dismissed from the EITI ranks following poor performance. Tullow holds shares in producing assets in both, and paid $214 million to Equatorial Guinea and $227 million to Gabon in 2013. The disaggregated figures, from two projects in Equatorial Guinea and ten in Gabon, will help to reveal some basic contours of the fiscal landscape in these largely opaque, oil-dependent countries, and permit observers and oversight actors to ask more informed questions of the state. For instance, we now know that Gabon’s government received in-kind revenues from Tullow for about half of the projects, and the license-by-license data on these transfers would allow observers to value the crude more accurately since its quality varies from field to field.

Managing expectations is another crucial use. Tullow is a major player in the fledgling oil sectors of Kenya and Uganda, countries where talk about the forthcoming bonanza has so far exceeded any output in barrels. The actual payments are a sobering reminder of how far both countries have to go before transformative revenues arrive: In 2013, Tullow paid Kenyan authorities $22 million, and $23 million to Uganda – sums of relatively little importance to their national budgets. Since neither country has joined the EITI, company reporting like Tullow’s is essential.

The uses for project-level data extend beyond these initial examples. One use that seems unlikely, however, is that such reporting will somehow undermine Tullow’s commercial viability. Rather, the company has shown that detailed reporting is feasible for oil companies, and it debunks some of the alarmist claims others have used to avoid this kind of transparency.

While Tullow has room to improve – it should disclose contracts in countries other than Ghana, and release data in a more user-friendly format than PDF files – its 2013 annual report represents an admirable step forward. We applaud the initiative and encourage other companies to follow suit.

Note: In some cases, we used the $105.7 average 2013 oil price provided by Tullow to calculate the value of in-kind revenues.

A snapshot from Tullow’s reporting of government payments.

Authors

Alexandra Gillies

Contributor