Nigeria: Updated Assessment of the Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on the Extractive Sector and Resource Governance

This is one of a series of country briefings produced by NRGI to summarize the evolving situation with respect to the pandemic and its economic impacts. The analysis it contains is subject to change with circumstances, and may be updated in due course.

Key messages

- The oil sector accounts for half of government revenue in Nigeria. Oil revenues for the first half of 2020 were 65 percent lower than anticipated, which will cause critical budget shortfalls both centrally and at the state level.

- Nigeria is requesting USD 11 billion in loans in the context of the pandemic, which would increase its debt stock by 50 percent.

- Some local oil companies may not survive the economic downturn and international companies (IOCs) may seek to sell some of their assets, interest permitting.

- Prospects for new investment are weak. Low prices, combined with uncertainty on key legislation, will likely push back investment decisions on a backlog of deep-water projects that are key to growing production.

- The current crisis underscores the risks inherent in Nigeria’s continued dependence on oil revenue. Even before the coronavirus pandemic and the price shock, chronic revenue shortfalls were an issue.

Summary of the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic

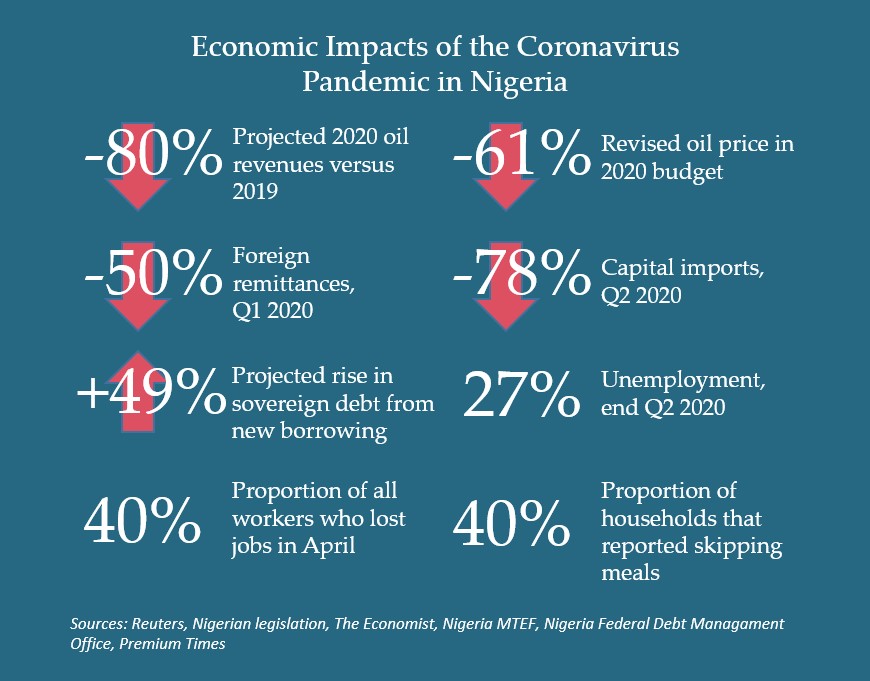

The combination of low oil prices and weak global demand, caused partly by the coronavirus pandemic, is hitting Nigeria hard. Although the oil sector represents less than 10 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), it accounts for half of government revenues and over 90 percent of foreign exchange. In May, the government predicted that 2020 oil revenues could be as much as 80 percent lower than planned. In July, the minister for finance, budget and national planning stated that Nigeria experienced a 65 percent decline in projected net revenues from the oil and gas sector in the first half of the year, due to the price drop and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) production cuts. In the second quarter the economy shrank by 6 percent, a loss some forecasts see deepening to 9 percent by year’s end, depending on oil prices and how well the country contains the virus.

The coronavirus pandemic’s impacts on the real economy and ordinary Nigerians have been no less dramatic. Mostly urban lockdowns have devastated the informal sector, which is estimated to account for 80 percent of all jobs. As many as 70 percent of informal sector workers were already at or below the poverty level, and Nigeria has the world’s highest number of people living in extreme poverty. The country’s statistics bureau estimated that four in ten working Nigerians lost their job in April alone. As the crisis goes on, there are also disturbing signs of rising food insecurity in some parts of the country. The lockdowns, together with floods and feed shortages, have undermined local production of poultry and some household staples. According to one government survey, up to three quarters of households are skipping meals since the pandemic started.

Meanwhile, banks rationing dollars is hurting key non-oil sectors like manufacturing and imports, notably those of food and pharmaceuticals. By July, consumer price inflation was up 12.8 percent year-on-year, with food-price inflation even higher. Some analysts warn that the government’s blanket ban on dollar sales to food and fertilizer importers risks worsening hunger. In the financial sector, bond yields dropped to a ten-year low, capital imports fell 78 percent, and an estimated $2.5 billion of bond-holder cash was stranded in the country. As the dollar shortage worsened, banks ratcheted up controls, like restrictions on dollar-based credit card purchases, while the government went after non-oil exporters that use foreign accounts. Critically, the global lockdowns that started in February halved foreign remittances, which give local businesses far more capital than oil. In 2018, for example, the one-plus million Nigerians living abroad remitted an estimated $23.6 billion—an amount equal to 6 percent of GDP, 80 percent of the federal budget and 11 times all foreign direct investment that year, including from oil.

Nigeria is not well prepared to cope with this crisis. The government passed a series of record-breaking budgets after the 2014 oil price collapse and borrowed heavily to finance a growing deficit. Debt service already consumes over half of government revenue and most fiscal buffers are depleted. In April, Nigerian officials told the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that the country faced an external financing gap of $14 billion. Many of its 36 state governments are insolvent as well.

Against these warning signs, the Buhari government’s commitment to fiscal discipline looks doubtful. The National Assembly did amend the 2020 budget in May, lowering the benchmark oil price by almost two thirds. But just three months later, the finance ministry signaled that 2021’s proposed budget would be the biggest yet, with a corresponding hike in the deficit.

To help support all this spending, the government is seeking $11 billion in fresh loans from the IMF, domestic banks, the World Bank and others. If successful, these would grow the debt stock by close to another 50 percent, though some lenders have delayed signing, saying they expect deeper reforms. In August, it was also reported that the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) had signed a $1.5 billion oil-backed loan with trading giant Vitol and other lenders—a troubling development, as Nigeria had until then avoided the risky, opaque world of resource-backed lending from traders. Looking ahead, there are tentative plans to harmonize exchange rates, devalue the naira for a third time and draw down smaller oil-revenue savings accounts, including the sovereign wealth fund’s stabilization fund. Officials are also fighting foreign creditors more aggressively, including a controversial $10 billion arbitration award over an unbuilt gas plant.

To help meet basic household needs, the government has distributed small cash payments and food to a limited number of mainly urban households. Food banks, places of worship, communities and crowdsourced donations have attempted to fill the gap. In May, the government announced a stimulus package that promised food aid, direct cash transfers and loans for households, small- and medium-sized enterprises and key non-oil sectors. Early data and anecdotes suggest that the actual outlays and numbers of people served have been far lower than projections, however.

The presidency has set up several committees and taskforces to explore ideas for managing the crisis, but most of their proposals have not gained traction. This is partly because responsibility for economic matters remains unsettled since the death of the president’s influential chief of staff, Abba Kyari, who died of COVID-19 in April.

Impact on the oil and gas sector

Low oil demand and prices, caused partly by the coronavirus pandemic, are putting heavy pressure on the sector’s outputs and economic fundamentals. At a central bank meeting in March, the head of the NNPC stated that low prices meant that Nigeria had 50 cargos of oil and 12 of liquefied natural gas that could not find buyers. Demand seems to have stabilized somewhat since then, and the government is navigating a production cut agreed earlier with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) by rebranding more of its crude oil as condensate. Still, the IMF forecasts that total oil and gas exports will decline by at least $26.5 billion this year.

The Buhari government’s response has been to prioritize cutting costs. For example, NNPC says it is pressing its upstream partners to reduce their production costs and is rolling back operations at its underperforming refineries. Top officials also announced in September that they would take the politically unpopular step of deregulating retail gasoline prices. While this effectively ends the costly, corrupt gasoline subsidy, it remains to be seen whether NNPC will stop withholding money from the treasury to cover its losses from supposedly wholesaling gasoline to retailers below cost. The government is also trying to restart private gasoline imports as a way to lower its import bill, though the dollar crunch makes that difficult.

Prospects for new investment in the sector are weak. The current low prices, combined with non-passage of the petroleum industry bill will likely push back investment decisions on a backlog of deep-water projects that are key to growing production. Looking further out, some analysts suggest that future price shocks, caused by falling global demand for oil, could undermine the economics of Nigerian deep-water projects. In July, Shell announced it was writing down its controversial offshore license OPL 245, which remains at the center of corruption trials in Italy and Nigeria. After officials expressed doubts about a major oil licensing round in May, in June the Department of Petroleum Resources opened bidding for 57 marginal oil fields. Many of these fields have little to no proven reserves, and options for financing look limited.

The local firms that now produce around a fifth of Nigeria’s oil are more vulnerable to shocks than are the international oil companies (IOCs). Some may not survive without further government bailouts. A few IOCs have announced plans to sell their Nigerian assets, and others could follow as they consolidate their portfolios in the wake of the oil price drop and wider global economic slowdown. In October, Chevron announced a 25 percent cut in their Nigeria staff due to the pandemic’s impact on oil demand.

After an early push to squeeze more cash from upstream companies, the government now seems to be reversing course, offering incentives for them to keep pumping. A pre-pandemic government focus was on strengthening fiscal terms now seems unrealistic. A 2019 law that hiked royalties on offshore oil has not been enforced.

In August 2020, the petroleum ministry submitted a new draft of the long-delayed petroleum industry bill (PIB) that instead cut key tax and royalty rates. However, in October, the ministry stated that the National Assembly had postponed consideration of the PIB until 2021, as it was prioritizing the 2021 budget appropriation bill. These developments raise longer-term questions: which actors will have the incentive and ability to keep investing in the sector, and what new concessions will Nigeria end up making to hold output even at current levels?

Impact on natural resource governance

To date, the coronavirus pandemic has not had any major impact on the resource governance agenda in Nigeria, which has long faced serious challenges. The crisis does throw some of Nigeria’s resource governance problems into sharper relief, not least NNPC’s practice of withholding billions of dollars a year in oil- and fuel-sale proceeds, which has been a longstanding challenge. The sector is in need of reform, and this money could help address the current crisis.

In August NNPC became a “supporting company” of the global Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), a move that requires a commitment to greater transparency. While overall prospects are doubtful, just prior to the EITI announcement, NNPC did take the significant step of publishing audited accounts for most of its subsidiaries, though not for the organization as a whole. One of the government’s coronavirus taskforces made strong recommendations for reining in NNPC’s use of oil-sale money, but these were quietly shelved. In the President’s recent statement of his remaining priorities while in office, “attaining sufficiency in…petroleum products” was the only oil-related item.

Looking forward

The current crisis underscores the high costs of Nigeria’s continued dependence on oil revenue. Even before the coronavirus pandemic and the price shock hit, the sector was stuck in a cycle of high uncertainty, boom-bust spending and diminishing returns. Production was mostly stagnant and budgeted oil revenues chronically underperformed. Already for 2019, before the crisis, treasury receipts from petroleum were 63 percent lower than planned. Simple demographics also show that more oil money is not the solution to Nigeria’s huge socioeconomic challenges: assuming a population of 195 million, total oil revenues for 2018—when prices were much higher—were just $93 per person.

Against these hard realities, NNPC says it wants to increase production and build housing, power stations and a dozen new hospitals when much of its own infrastructure is in disrepair. An overhaul of the oil revenue collection system looks unlikely, even as citizens face the worst economic recession in 30 years.

Nigeria’s only way out of oil dependence’s recurring destruction may be to plan a managed oil sector decline that allows the country to see a future for itself after oil.

Nafi Chinery is the West Africa regional manager (anglophone) for the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Aaron Sayne is a senior governance officer at NRGI. Alexandra Gillies is an NRGI advisor.

Authors

Nafi Chinery

Africa Director

Aaron Sayne

Lead, Domestic Energy Transition

Alexandra Gillies

Contributor