Close to Home: The Critical Importance of Subnational Governance in Oil, Gas and Mining

This piece originally appeared in shorter form as a Brookings Institution blog post.

For years, economists and political scientists have studied national governments throughout the world and advised about how to optimize resource revenues from extraction for long-term development. There are numerous policy disciplines that a country must get right to reap the full benefits. (These are addressed in detail in the Natural Resource Charter and global initiatives such as the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) offer an implementing framework focused on transparency and accountability in extractives.)

A major challenge that is often unaddressed by development plans is the governance of extraction by communities closest to a mine or oil and gas field. In most countries, national governments negotiate extraction contracts with companies and collect the revenues, but it is those closest to the extraction site that see their physical and economic landscape change most dramatically. Experience working on local governance issues in resource-rich countries has shown that for a country to fully benefit, subnational governance issues must be addressed.

An extractives site in Myanmar. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI.

Why subnational governance work really matters

One obvious reason for addressing subnational governance is that local dissatisfaction can derail an entire project, as a scan of headlines will indicate. Several Native American tribes have physically blocked construction of a pipeline in North Dakota, saying they were not properly consulted in its planning and are concerned that the pipeline will impact their water supply and threaten access to sacred sites. Employees at a phosphate mine in Togo are on strike demanding better wages and more protective gear. Anthropologists and environmental activists have tried to bring attention to social and environmental effects for years, but the local impacts are often treated as separate issues instead of something that impacts the nation’s chances of benefiting from resource wealth. Researchers at the Harvard Kennedy School found that community conflicts over environmental and social concerns can cost up to USD 20 million a week in lost value for large-scale operating mines.

It’s not just a question of lost revenues. When members of local communities do not feel like they are benefiting from a national extraction project, conflict can result. There have been 20 resource-fueled civil wars since World War II. While Myanmar has undergone great political transition in recent years, the government has struggled to bring conflict with various ethnic groups to an end. One of the key steps to ending these conflicts and bringing lasting peace to the country is addressing how the costs and benefits of natural resources are shared between the ethnic groups and the national government.

Many national governments already share resource management powers with local governments. Approximately 30 of the 58 countries assessed in the 2013 Resource Governance Index featured some form of revenue sharing between the national and subnational authorities. The responsibilities shared with local governments are often significant. For example, Bolivia decentralized more than USD 2 billion of its oil revenues in 2012, amounting to more than USD 1,000 per capita per year in some areas. Some districts in Nigeria receive more than 80 percent of their revenues from resource projects. In Indonesia, local governments have the power to grant—or deny—licenses for many mining projects. When development actors only address resource management issues with national governments, they risk missing these large areas of impact.

Unfortunately, the design of power or revenue sharing systems is often done in a reactionary manner. In some cases, poor design can lead to gaps or overlapping national and local government authority. In others, it can increase the opportunity for conflict, corruption and waste. In Peru, some local leaders in mining regions attempted to foment violent protests in order to compel additional revenue transfers from the national government when commodity prices rose between 2005 and 2008. When powers are decentralized without adequate institutional preparation, capacity gaps can emerge as there is a sudden demand for extractive expertise in more locations throughout the country.

How to approach subnational resource governance

Supporting good resource governance at the local level is not easy. Even the definition of the problem looks different at the subnational level—academics debate how to characterize and whether there is a subnational resource curse. While some studies show real income levels rose in communities living closest to mines compared to other communities in the same country, others studies show that local economies were harmed by sudden large increases in public spending.

NRGI researchers have recently concluded a series of policy papers, including a synthesis paper, to support local governments and civil society actors as they aim to improve governance of natural resource wealth. The research is the fruit of eight years of working side-by-side with civil society and local government partners in resource-rich subnational areas throughout the world. The headline? While many of the good practices required at the national level do matter and apply at the subnational level, one cannot simply cut-and-paste national level solutions into subnational resource governance challenges.

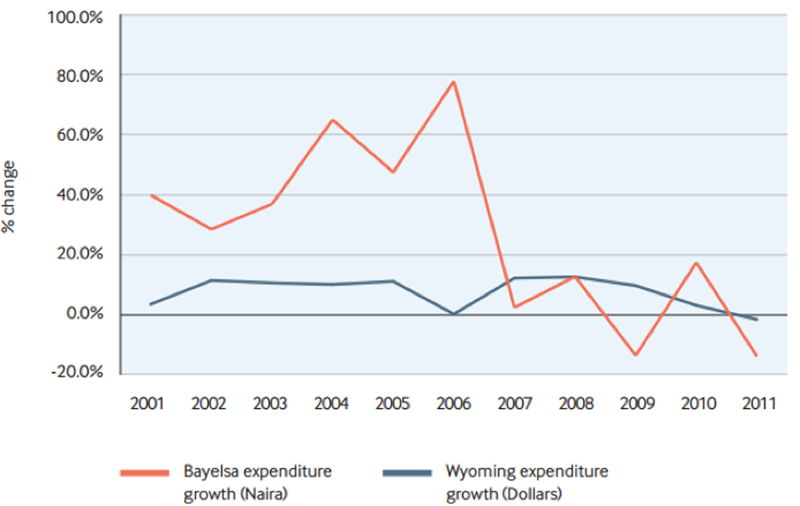

One of the biggest challenges at the local level is that the responsibility delegated to local authorities is not matched with the institutions and policy options needed to manage associated challenges. Decades of research has shown that the large, volatile and finite nature of resource revenues can distort economies and lead to wasteful government spending. The prevailing wisdom is to save some of the resource revenues in a manner that counters the distortion or allows for more flexibility when prices change. Some subnational governments have been able to implement these policy recommendations, mirroring national level best practices. The below figure illustrates how the U.S. state of Wyoming was able to smooth expenditure spending during volatile commodity prices by using a savings fund. Meanwhile, the state of Bayelsa in Nigeria had more than an 80 percent change in spending.

Many resource-rich subnational governments simply don’t have that option: the national government has strict rules that forbid subnational governments from borrowing or saving revenues. In Indonesia, for example, district governments, which receive 6 percent of the oil revenue from projects in their district, are required to repay the national government any revenue they don’t spend by the end of the year. The local leaders of Bojonegoro, an oil-rich district in Indonesia with just over a million people, are working hard to counter this problem. Through intense lobbying, they have convinced the national government to allow them to create a savings fund and are in the process of passing legislation to create the first such fund in the country. The broader policy lesson is that subnational governments must be given the tools to address known resource revenue challenges. Sometimes, this means changing the national rules.

Short- to medium-term expenditure volatility in Bayelsa and Wyoming

Just because a local government has powers does not mean it has the capacity to manage things well. In the 1980s in Argentina, for example, provincial governments were given the power to license land for mineral exploitation. The local governments had such poor boundary information, cadaster tracking and security of tenure that mining companies stayed away. It was not until 1993—when the provinces agreed to create a uniform cadaster system—that companies began to engage. The number of foreign mining investments in Argentina went from four in 1989 to 80 in 2009. In this case, even though the decision-making power remained at the local level, a uniform system allowed for greater confidence from the industry. Interestingly, as the new government is trying to restart the Argentine economy and address major development challenges, earlier this month Argentina’s national government announced efforts to further streamline mining regulations across provinces to attract more investment.

The capacity of local governments can also be hindered by power asymmetries between national and local governments. This can often be seen in the challenges local governments have collecting revenues from national government or extractive companies. NRGI profiles this problem in a case study about a mining community in Asutifi, Ghana. When the mine began to produce gold in 2006, local leaders in Asutifi knew they were entitled to a property tax and percentage of the royalties, but they did not have access to the contract between the company and the government or production information to understand their amount due. The leaders complained that there was a long bureaucratic procedure to get the royalties, which included unpredictable delays from the national government. As a result, what money was received locally was spent haphazardly, reducing the community’s trust of the local government. NRGI worked to improve the understanding of local leaders and civil society about the revenue calculations so they could better advocate for their due.

As at the national level, corruption and nepotism can complicate good governance solutions to natural resource management. While there is some empirical evidence that fiscal decentralization correlates with lower levels of corruption, decentralization also distributes the opportunities for corruption more widely and often with less formal oversight. Civil society and journalists who often can put a check on corruption at the national level tend to have fewer resources and less access to information at the local level.

A framework for subnational resource governance policy analysis and recommendations

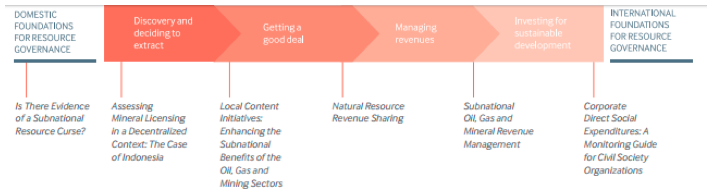

The Natural Resource Charter provides a useful framework to analyze the decisions that governments need to make in converting natural resource wealth below the ground into long-term sustainable development above the ground. From the decision to extract to investing for sustainable development, each step in the decision chain is crucial for governments to avoid common pitfalls of the “resource curse.” The extent to which national governments delegate powers for each decision to subnational governments vary greatly from country to country. NRGI’s research has shown ways to consider the implications for subnational governance across the decision chain. Because of its area of expertise, NRGI’s research focuses on governance issues related to licensing and revenue management more than direct social and environmental impacts.

At each step in the decision chain, policymakers can consider how governance challenges are similar and different at the subnational level. Even when subnational governments are not delegated the full authority for one area, there are often still implications for subnational governance. For example, even if licensing powers rest largely with the national government, clarity of local tenure systems is critical to ensure a smooth transfer of land and resource rights. NRGI’s series of policy papers have raised a few key points at each step of the decision chain:

The good news is that with support and access to information, many subnational governments are leading the charge for better resource management. Learning from their counterparts in Bojonegoro, civil society groups and local governments in the Compostela Valley of the Philippines were able to come together in a multi-stakeholder discussion and create detailed transparency mechanisms. Mining in the Philippines is often very contentious and in many regions there is little trust between communities, governments and the industry. “Transparency templates” and discussion forums at the local level informed a national multi-stakeholder implementation of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Local innovations like these can keep the momentum going during national efforts to improve resource governance.

Daniel Kaufmann is the president and CEO of the Natural Resource Governance Institute and a non-resident senior fellow at Brookings. Rebecca Iwerks is a lawyer specializing in the intersection between development and human rights. She works as a consultant with NRGI’s subnational governance program.

This paper was drafted in conjunction with a panel discussion on the topic at the Overseas Development Institute and the launch of a paper synthesizing NRGI’s work on subnational governance.

For years, economists and political scientists have studied national governments throughout the world and advised about how to optimize resource revenues from extraction for long-term development. There are numerous policy disciplines that a country must get right to reap the full benefits. (These are addressed in detail in the Natural Resource Charter and global initiatives such as the Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) offer an implementing framework focused on transparency and accountability in extractives.)

A major challenge that is often unaddressed by development plans is the governance of extraction by communities closest to a mine or oil and gas field. In most countries, national governments negotiate extraction contracts with companies and collect the revenues, but it is those closest to the extraction site that see their physical and economic landscape change most dramatically. Experience working on local governance issues in resource-rich countries has shown that for a country to fully benefit, subnational governance issues must be addressed.

An extractives site in Myanmar. Photo by Lauren DeCicca for NRGI.

Why subnational governance work really matters

One obvious reason for addressing subnational governance is that local dissatisfaction can derail an entire project, as a scan of headlines will indicate. Several Native American tribes have physically blocked construction of a pipeline in North Dakota, saying they were not properly consulted in its planning and are concerned that the pipeline will impact their water supply and threaten access to sacred sites. Employees at a phosphate mine in Togo are on strike demanding better wages and more protective gear. Anthropologists and environmental activists have tried to bring attention to social and environmental effects for years, but the local impacts are often treated as separate issues instead of something that impacts the nation’s chances of benefiting from resource wealth. Researchers at the Harvard Kennedy School found that community conflicts over environmental and social concerns can cost up to USD 20 million a week in lost value for large-scale operating mines.

It’s not just a question of lost revenues. When members of local communities do not feel like they are benefiting from a national extraction project, conflict can result. There have been 20 resource-fueled civil wars since World War II. While Myanmar has undergone great political transition in recent years, the government has struggled to bring conflict with various ethnic groups to an end. One of the key steps to ending these conflicts and bringing lasting peace to the country is addressing how the costs and benefits of natural resources are shared between the ethnic groups and the national government.

Many national governments already share resource management powers with local governments. Approximately 30 of the 58 countries assessed in the 2013 Resource Governance Index featured some form of revenue sharing between the national and subnational authorities. The responsibilities shared with local governments are often significant. For example, Bolivia decentralized more than USD 2 billion of its oil revenues in 2012, amounting to more than USD 1,000 per capita per year in some areas. Some districts in Nigeria receive more than 80 percent of their revenues from resource projects. In Indonesia, local governments have the power to grant—or deny—licenses for many mining projects. When development actors only address resource management issues with national governments, they risk missing these large areas of impact.

Unfortunately, the design of power or revenue sharing systems is often done in a reactionary manner. In some cases, poor design can lead to gaps or overlapping national and local government authority. In others, it can increase the opportunity for conflict, corruption and waste. In Peru, some local leaders in mining regions attempted to foment violent protests in order to compel additional revenue transfers from the national government when commodity prices rose between 2005 and 2008. When powers are decentralized without adequate institutional preparation, capacity gaps can emerge as there is a sudden demand for extractive expertise in more locations throughout the country.

How to approach subnational resource governance

Supporting good resource governance at the local level is not easy. Even the definition of the problem looks different at the subnational level—academics debate how to characterize and whether there is a subnational resource curse. While some studies show real income levels rose in communities living closest to mines compared to other communities in the same country, others studies show that local economies were harmed by sudden large increases in public spending.

NRGI researchers have recently concluded a series of policy papers, including a synthesis paper, to support local governments and civil society actors as they aim to improve governance of natural resource wealth. The research is the fruit of eight years of working side-by-side with civil society and local government partners in resource-rich subnational areas throughout the world. The headline? While many of the good practices required at the national level do matter and apply at the subnational level, one cannot simply cut-and-paste national level solutions into subnational resource governance challenges.

One of the biggest challenges at the local level is that the responsibility delegated to local authorities is not matched with the institutions and policy options needed to manage associated challenges. Decades of research has shown that the large, volatile and finite nature of resource revenues can distort economies and lead to wasteful government spending. The prevailing wisdom is to save some of the resource revenues in a manner that counters the distortion or allows for more flexibility when prices change. Some subnational governments have been able to implement these policy recommendations, mirroring national level best practices. The below figure illustrates how the U.S. state of Wyoming was able to smooth expenditure spending during volatile commodity prices by using a savings fund. Meanwhile, the state of Bayelsa in Nigeria had more than an 80 percent change in spending.

Many resource-rich subnational governments simply don’t have that option: the national government has strict rules that forbid subnational governments from borrowing or saving revenues. In Indonesia, for example, district governments, which receive 6 percent of the oil revenue from projects in their district, are required to repay the national government any revenue they don’t spend by the end of the year. The local leaders of Bojonegoro, an oil-rich district in Indonesia with just over a million people, are working hard to counter this problem. Through intense lobbying, they have convinced the national government to allow them to create a savings fund and are in the process of passing legislation to create the first such fund in the country. The broader policy lesson is that subnational governments must be given the tools to address known resource revenue challenges. Sometimes, this means changing the national rules.

Short- to medium-term expenditure volatility in Bayelsa and Wyoming

Just because a local government has powers does not mean it has the capacity to manage things well. In the 1980s in Argentina, for example, provincial governments were given the power to license land for mineral exploitation. The local governments had such poor boundary information, cadaster tracking and security of tenure that mining companies stayed away. It was not until 1993—when the provinces agreed to create a uniform cadaster system—that companies began to engage. The number of foreign mining investments in Argentina went from four in 1989 to 80 in 2009. In this case, even though the decision-making power remained at the local level, a uniform system allowed for greater confidence from the industry. Interestingly, as the new government is trying to restart the Argentine economy and address major development challenges, earlier this month Argentina’s national government announced efforts to further streamline mining regulations across provinces to attract more investment.

The capacity of local governments can also be hindered by power asymmetries between national and local governments. This can often be seen in the challenges local governments have collecting revenues from national government or extractive companies. NRGI profiles this problem in a case study about a mining community in Asutifi, Ghana. When the mine began to produce gold in 2006, local leaders in Asutifi knew they were entitled to a property tax and percentage of the royalties, but they did not have access to the contract between the company and the government or production information to understand their amount due. The leaders complained that there was a long bureaucratic procedure to get the royalties, which included unpredictable delays from the national government. As a result, what money was received locally was spent haphazardly, reducing the community’s trust of the local government. NRGI worked to improve the understanding of local leaders and civil society about the revenue calculations so they could better advocate for their due.

As at the national level, corruption and nepotism can complicate good governance solutions to natural resource management. While there is some empirical evidence that fiscal decentralization correlates with lower levels of corruption, decentralization also distributes the opportunities for corruption more widely and often with less formal oversight. Civil society and journalists who often can put a check on corruption at the national level tend to have fewer resources and less access to information at the local level.

A framework for subnational resource governance policy analysis and recommendations

The Natural Resource Charter provides a useful framework to analyze the decisions that governments need to make in converting natural resource wealth below the ground into long-term sustainable development above the ground. From the decision to extract to investing for sustainable development, each step in the decision chain is crucial for governments to avoid common pitfalls of the “resource curse.” The extent to which national governments delegate powers for each decision to subnational governments vary greatly from country to country. NRGI’s research has shown ways to consider the implications for subnational governance across the decision chain. Because of its area of expertise, NRGI’s research focuses on governance issues related to licensing and revenue management more than direct social and environmental impacts.

At each step in the decision chain, policymakers can consider how governance challenges are similar and different at the subnational level. Even when subnational governments are not delegated the full authority for one area, there are often still implications for subnational governance. For example, even if licensing powers rest largely with the national government, clarity of local tenure systems is critical to ensure a smooth transfer of land and resource rights. NRGI’s series of policy papers have raised a few key points at each step of the decision chain:

- Deciding to extract/licensing: Governments must be sure to coordinate licensing information systems vertically (between the national and subnational governments) and horizontally (between subnational governments), while recognizing the full spectrum of land rights to reduce conflict and produce better planning.

- Getting a good deal (revenue sharing): Any revenue sharing scheme should have clear objectives aligned with subnational expenditure responsibilities and management capacities.

- Getting a good deal (local content): Local content plans should be coordinated with local development plans so that new businesses can be created more easily and have lasting impact. The national government must be transparent about the negotiating process and the real costs associated with local content promises.

- Managing resources: Local governments should implement revenue management best practices, including using fiscal rules. National governments must allow local governments the tools to match their resources.

- Investing for sustainable development: Local and national governments can use the resource revenues as an opportunity to improve their subnational investment systems so that future spending is more efficient. At the same time, both levels of government can foster non-extractives areas of the economy to create long-term growth.

- Transparency: Information must be disaggregated on a project-by-project basis and available in formats that can be accessed and absorbed by subnational communities at each step in the decision chain.

The good news is that with support and access to information, many subnational governments are leading the charge for better resource management. Learning from their counterparts in Bojonegoro, civil society groups and local governments in the Compostela Valley of the Philippines were able to come together in a multi-stakeholder discussion and create detailed transparency mechanisms. Mining in the Philippines is often very contentious and in many regions there is little trust between communities, governments and the industry. “Transparency templates” and discussion forums at the local level informed a national multi-stakeholder implementation of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Local innovations like these can keep the momentum going during national efforts to improve resource governance.

Daniel Kaufmann is the president and CEO of the Natural Resource Governance Institute and a non-resident senior fellow at Brookings. Rebecca Iwerks is a lawyer specializing in the intersection between development and human rights. She works as a consultant with NRGI’s subnational governance program.

This paper was drafted in conjunction with a panel discussion on the topic at the Overseas Development Institute and the launch of a paper synthesizing NRGI’s work on subnational governance.

Authors

Daniel Kaufmann

President Emeritus