Governance Matters: Civil Society Voice and Performance at the World Cup

Originally posted on Huffington Post.

These days, a soccer World Cup is a multi-billion dollar project, with a number of financial "winners," such as FIFA, and many losers, given the development priorities that are sacrificed to build gleaming stadia and dedicated infrastructure, much of it with little post-games use.

Does this also mean that one can explain a nation's success at the cup largely by money?

A number of analysts and organizations making predictions about the World Cup thought so. One large financial firm, ING, utilized the monetary market value of the national team(aggregating the market value of each player) to predict that the World Cup winner would be Spain, the highest valued national team at close to $1 billion!

Or perhaps money matters in other ways, such as how large a country's economy is, how well paid the team manager is, or whether the national team was able to recruit a foreign manager. We also hear that oil riches might have bought the right to host the World Cup, as has been said of Qatar, or can buy a top European football club. But do national teams from resource-rich countries perform better at the World Cup?

Beyond money matters, we read about population size as a critical determinant (much larger potential pool of soccer players), and also aboutthe "luck of the draw." When the lottery took place to assignthe 32 World Cup teams to the eight groups for the first stage,many lamented that their national teams had been assigned to a "group of death," while others were placed with weaker contenders and, thus, seemingly easy groups.

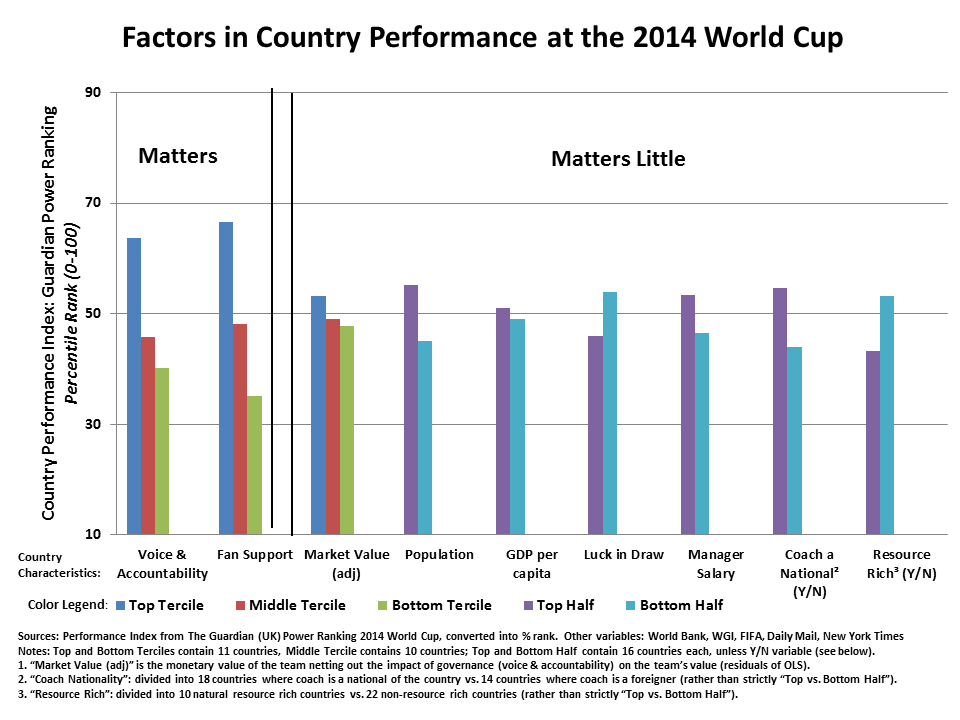

Analyzing the statistical evidence provides some surprising insights. It turns out that in looking at what differentiates success from failure in advancing to the second stage (round of 16) of this year's World Cup, money did not make a difference. Neither the monetary value of a team, nor the salary of the team's manager (nor whether the manager is a national or foreigner) mattered statistically. Controlling for other factors, the size of a country's population or economy did not make much of a difference either. In addition, whether the country is resource-rich or not had no impact on the performance of the national team whatsoever.

Some of these statistical results would not shock those who watched themodestly valued Costa Rica advance by sending wealthy Italy home, or those who witnessed highly paid powerhouses such as England, Spain and Portugal also exit the World Cup early. Further, our analysis finds that the "luck of the draw" regarding the caliber of the rivals each country faced in their first stage groupings of the World Cup, or for that matter the average height of the team's players, did not matter either.

Beyond Luck and Money

If none of these commonly mentioned factors make a difference in explaining World Cup success,then what does matter? Our statistical analysis points to two relevant determinants.

First, the quality of democratic governance of the country is important. Whether the countryexhibits high levels of voice and democratic accountability—namely protecting civil society space, media freedoms, and civil and political liberties—matters significantly, controlling for other factors. If, among its World Cup peers, a country rated in the top third in the voice and accountability indicator of the

Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), it had a 70 percent chance of advancing to the round of 16, while if it ranked in the bottom third it only had a 30 percent probability of advancing.

Second, we find that the extent of the fan base at the World Cup (number of fanstraveling to the cup to cheer for their national team) also matters, explaining part of the success of teams from North, Central and South America in advancing to the second stage.

Both determinants of soccer success may be related, reflecting twosides of a coin. To an extent, fan support for their national team may be the counterpart to the enabling accountability environment provided by each government (bottom-up versus top-down). Citizen empowerment and participation does matter in soccer as well, presumably because a free media and uncensored fan base passionately encourages their national team, while also holding themaccountable.

This ought not to shock us, since the importance of these factors extend well beyond soccer. We know the extent to which democratic governance, civil society voice, and accountability matters for development success in general, for the success of public institutions and NGOs, and also in particular in countries seeking to harness their own natural resources for socio-economic progress.

Governance and Democratic Accountability

It may not be a coincidence, therefore, that countries like Russia, Cameroon, Honduras and Iran went out during the first round, while Costa Rica, Chile, Uruguay, Switzerland and the United States advanced. Following the games in the second round, eight countries qualified for the next stage, and, with countries like Algeria and Nigeria exiting at that stage, no team with even relatively low standards of democratic governance (i.e., rating in the bottom half of voice andaccountability indicator in the WGI) made it to the quarterfinals.

We all know that Germany won the cup, following its lopsided win against Brazil in the semifinal, and then the tight1-0 win in extra time over Argentina in the final. Both Brazil and Argentina have made major strides in terms of their standards of democratic governance since their dark military dictatorship days of a generation ago. Yet it is still the case that Germany exhibits nowadays the highest standards in voice and accountability among the World Cup nations, alongside Netherlands and Switzerland. And Germany had a vastly larger fan base than these other two European countries, similar to Argentina, and only significantly surpassed by the United States, which drew close to 200,000 visitors.

In fact, if we statistically analyze the overall team performance throughout the World Cup—not just the early rounds—similar results emerge. We analyzed the links between a nation's overall cup performance as measured by the Guardian's PowerIndex (with Germany on top, followed by Argentina, Netherlands and Brazil, and then the other 28 teams) and the host of potential determinants discussed above. The results are similar: voice and democratic accountability, as well as a country's fan base, are found to be important, while monetary and wealth variables and "luck of the draw" matter much less, if at all (see figure below). And countries that are resource-rich, or opted to select a foreign coach, if anything, performed somewhat less well.

At a basic level, it is also informativeto look at the ratings by

Freedom House, which classify countries around the world into three categories in terms of their political freedoms and civil liberties: free, partly free, or not free. Out of the 209 countries in the world, only 90 of them, or 43 percent, rate as free. But those countries with fuller civil liberties had a betterchance of qualifying to the World Cup; in fact two-thirds of the countries in the World Cup are "free." Of those that succeededto make it to the second round, three-quarters were "free," while among the last eight countries standing at the cup, no country was among the "not free" category, only one was "partly free,"and the other seven (88 percent) were fully "free." By the semi-finals, all four remaining countries were "free," according to Freedom House.

What Makes the Difference

Obviously, even if governance matters, winning games is not all about democratic governance at the national level, andabout passionate "civil society" support in the stadium for a team. Governance also makes a big difference at an organizationallevel, namely the cohesiveness and effectiveness of a team beyond the individual quality of each player. In fact, in previous writings we have offered one definition of good governanceas the ability of a team to be more than the sum of its parts. During this Cup, Costa Rica, Chile, France, the United States and Germany were illustrations of good governance at the team level, in contrast to Cameroon, Ghana, Italy or Spain, each producing so little in spite of their individual stars. In the South Africa World Cup four years ago, Ghana exemplified good governance as a team, in contrast then with France and Argentina, the latter being at the time poorly managed by Diego Maradona.

There is an implicit message from successful soccer nationsto FIFA: Democratic governance matters, and so does the fan base of a country. Increasingly, people from countries exhibiting high levels of openness and democratic accountability object to this opaque and autocratically run organization, increasingly pointing to the dire need for a democratic transition at FIFA. There is still a lot of noise about corruption at FIFA—even in this week’s Huffington Post—but we need to bear in mind that one doesn't fight corruption by "fighting corruption": in fact, corruption is a nefarious symptom of systemic governance failure. Thus, to tackle it, openness and democratic accountability need to be put in place.

More broadly, we are reminded that just as we have learnedthat sending billions of dollars in foreign aid, or being rich in natural resources, doesn't guarantee socio-economic development for a country and benefits to the people, neither oil riches nor money alone can "buy" national soccer success either. What makes the difference is good governance and democratic accountability.

Daniel Kaufmann is president of the Natural Resource Governance Institute (formerly the Revenue Watch Institute - Natural Resource Charter) and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. He blogs on governance at www.thekaufmannpost.net and tweets @kaufpost.

Authors

Daniel Kaufmann

President Emeritus