Modeling for the Masses: Why the IMF Should Open Up the FARI Model for Public Use

Resource-endowed countries face a fiendish problem whenever they negotiate with an extractive company: how to get a good deal?

This is a challenge wherever oil, gas or minerals abound, in countries rich and poor. Failure to get a good deal has cost many countries billions of dollars in lost or foregone public revenues.

The IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department’s (FAD) “Fiscal Analysis of Resource Industries” (FARI) model has become the gold standard for project lifecycle modeling; it supports the design of fiscal terms and negotiation of resource contracts. The model is used extensively across the 29 countries designated resource-rich by the IMF, as part of FAD’s technical assistance to governments. It has been used by countries opening up new resource deposits, re-negotiating existing deals, and forecasting revenues during periods of volatile prices.

We encourage the IMF to release the FARI model into the public domain, and more openly share the underlying assumptions, data and results from FARI analysis wherever possible. The reason is simple: there are parties beyond those receiving technical assistance from the IMF who can apply their own expertise to make productive use of the model.

The models are incredibly powerful, as seen in Guinea, where decades of mismanagement, corruption, and impunity have left a legacy of poor deals that the current government is intent on reviewing. In some cases, the revenue foregone from these agreements has amounted to billions of dollars, while the country’s tax revenues barely amounted to USD 1.1 billion in 2013. The IMF FAD has provided project level modeling to the government in order to forecast revenue, and Guinea’s mining contract review committee and its advisors have been adapting these models to inspect existing mining contracts and renegotiate them where needed. Some of these reviewed deals, like the $20 billion investment plan in the iron ore mountains of Simandou, have the potential to unleash truly transformational development for the country.

While Guinea has received technical assistance from the IMF, not all countries have. They could use fiscal modeling to their advantage in a number of ways:

Deal analysis: Deals like those in Guinea have implications for generations to come. But how does one know whether a deal will bring a fair return to citizens? Making these deals solid and lasting requires a deeper common understanding of them and an open discussion about choices made at the negotiating table. When part of a gas agreement was recently leaked in Tanzania, lack of understanding of the deal created confusion and some unfounded allegations. To avoid just such scenarios, the government of Guinea disclosed all its mining contracts to strengthen credibility and accountability.

Monitoring contracts: But Guinea is not the only one disclosing its contracts. In fact there are now 225 contracts available online. This number is expected to grow rapidly as companies and governments release more contracts, in part as a result of the new EITI standard. Modeling contracts facilitates understanding of the terms, and helps stakeholders discern whether revenue flows match contract terms across time. With public scrutiny turning to these contracts, there is an increased demand to monitor whether parties to the agreements are respecting their fiscal term, and therefore whether auditors should be involved.

Revenue forecasting: Many resource-rich countries anticipate significant increases in GDP and revenues if commodity prices remain buoyant. These projections are often based on the models put forward by the IMF. But these calculations can better serve the public interest if they are subject to wider understanding and scrutiny. A critical mass of informed stakeholders can act as a buffer against over-inflated expectations or unfounded optimism ahead of unanticipated shortfalls.

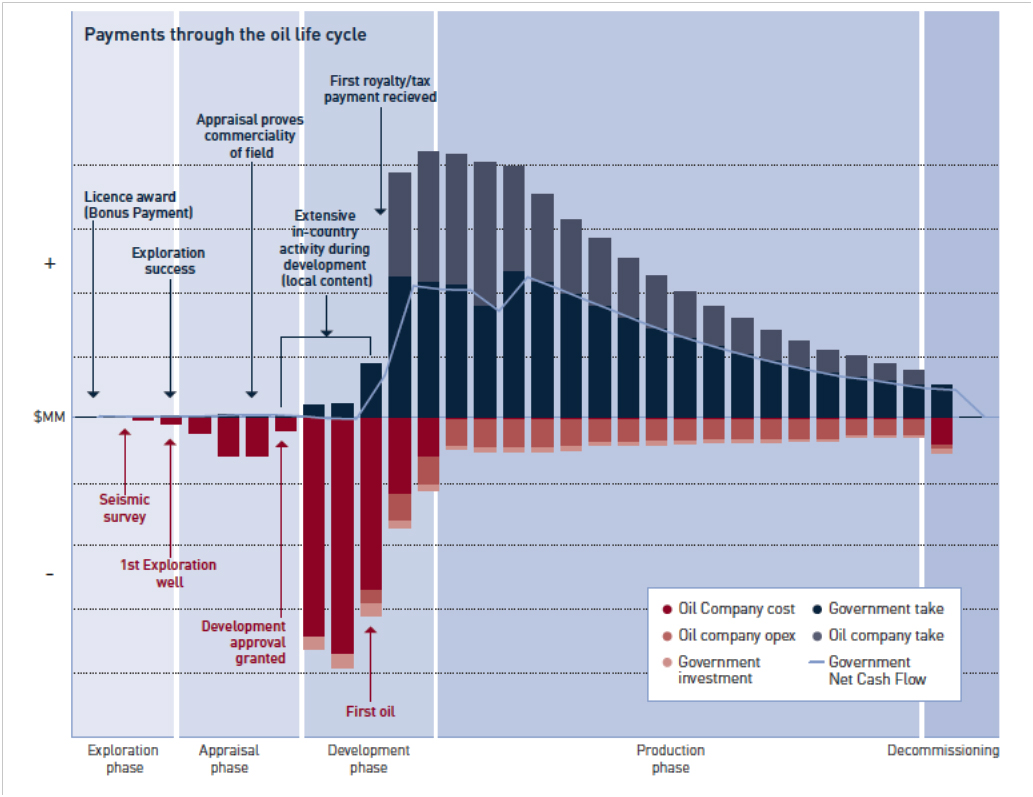

Building citizen understanding: Citizens often have elevated expectations following natural resource discoveries. But it can often take as long as a decade between the first discovery and the time when large revenues hit government coffers. At our June conference in Oxford, one panelist shared the story of a Liberian magazine that reported that the government received $14 billion from a US oil company, creating anger and confusion among members of the public. In fact, the $14 billion figure was merely a projection of how much money might be generated over the entire project lifetime. Such miscommunication is easier to combat when the basis for these claims is more readily subject to public scrutiny.

Source: Tullow, CR report

The increased transparency in contract disclosure and in payments made to government are both crucial steps. But to have greater accountability and understanding of the above issues, we need to open up the discussion on how the projects are modeled.

Talking about resource modeling may not sound very enthralling at first, but it is generating growing interest and public debate among experts and civil society actors around the world. The list of organizations working on this topic continues to grow, reflecting the growing public appetite for openness and better communication around resource deals and what they contain. As examples, Global Witness released its own economic model with calculations from Uganda; Open Oil is developing an open-source oil model to utilize open resource contracts; and Oxford Policy Management is working on projections of resource revenues and project-level forecasts.

We see two important steps that could be taken right away. First, the model most widely used in this field, the IMF FARI, should be released into the public domain, and with as much of the supporting assumptions, data and results as is feasible. Second, those of us engaged in these questions should begin a conversation on how to build a more open modeling community, capitalizing on the growing availability of relevant data in the public domain.

Prices change, plans change and scenarios become outdated. An open-source FARI model, alongside a library of open-source benchmarks, would allow a variety of stakeholders in resource-rich countries to learn how scenarios may change with new information, and would promote better-informed policy debates, even at times when IMF expertise may not be available in-country.

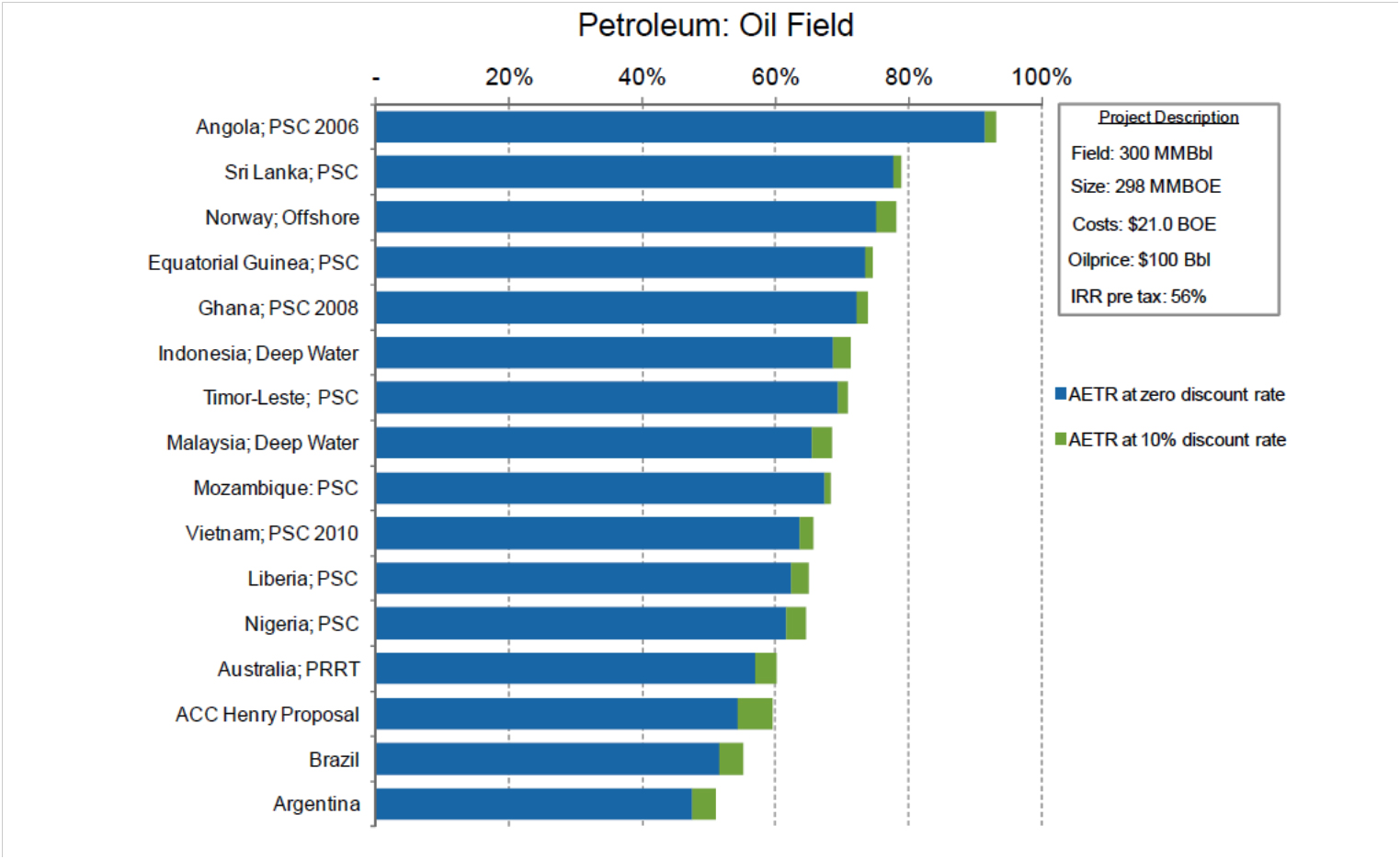

Average effective tax rates (on profits) for different oil contracts based on IMF FARI model. Publishing a wider set of international benchmarks like these would help governments and citizens to better evaluate deals.

Having a more open approach to fiscal modeling is critical not only for increased public understanding and participation, but also for better coordination and forecasting within government. In too many countries the ministry of mines (which often leads contract negotiations), the ministry of finance (in charge of budget planning), and the tax authorities use different models, leading to duplicated effort but not nearly enough learning or scrutiny. It is also important to give companies in the private sector a standard model to which they can compare their own projections and use to explain any deviations.

At NRGI we aim to improve the use of models (for example through increased data availability), and promote such use and understanding of models in resource-rich countries. On the usability side, we are currently working with partners to upgrade the resource contracts database, to maximize inter-operability with fiscal models, and also improve revenue data such as that generated in EITI reports. We are also supporting EITI implementing countries to make reports digital and more widely used. And we’re working to support countries with independent fiscal analysis, and capacity building to use extractives data for better policy-making.

The IMF’s leadership on this important issue could catalyze an exciting new frontier of work with open data and open tools, and bolster wider efforts to use data more effectively to promote effective and accountable governance.

NRGI is convening interested groups and individuals working on open data for extractives and fiscal modeling of extractive projects. If you wish to be involved, please contact us: jcust@resourcegovernance.org and dmihalyi@resourcegovernance.org.

Jim Cust is NRGI’s head of data and analysis. David Mihalyi is an NRGI economic analyst.