Is the Democratic Republic of Congo’s New Mining Fiscal Regime Up to the Task?

The increasing use of renewable energy technology is driving major demand for minerals such as copper and cobalt, a key ingredient in electric batteries. This could be a golden opportunity for the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the majority of the population lives in poverty. The country produces more than a million tons of copper per year, holds the largest reserves of cobalt in the world and is responsible for 60 percent of global cobalt production. Miners extract both metals from deposits that lie in the copper belt of southeastern Congo.

The fiscal regime for mining is critical for DRC’s ambitions. Setting fiscal terms such as royalties and income tax rates too high could limit investors’ interest and even give an additional impetus to research in cobalt substitutes in electric battery technologies. Setting them too low would deprive the Congolese of much needed public revenue and solely benefit foreign-owned mining companies. This is why the adoption of a revised mining code last March and related regulations in June were of utmost interest to Congolese citizens, who are now looking toward general elections this December.

In 2016, we published a report describing the “dead-end” the mining code review process faced at that time. We argued that the government should remain committed to reform using a consultative approach. The 2002 mining code had contributed to a wave of investments in post-war Congo. But it badly needed updating to bring additional benefits to local populations and to provide a fairer balance in the distribution of mining rents. Deep disagreements between the government and industry on the content of the fiscal regime had prevented constructive debate after the draft mining code was submitted to parliament in March 2015. Key improvements around transparency and local development—including financial provisions for community development, transparency of payments and beneficial ownership information, and and direct payment of revenues to subnational governments—were all basically held hostage.

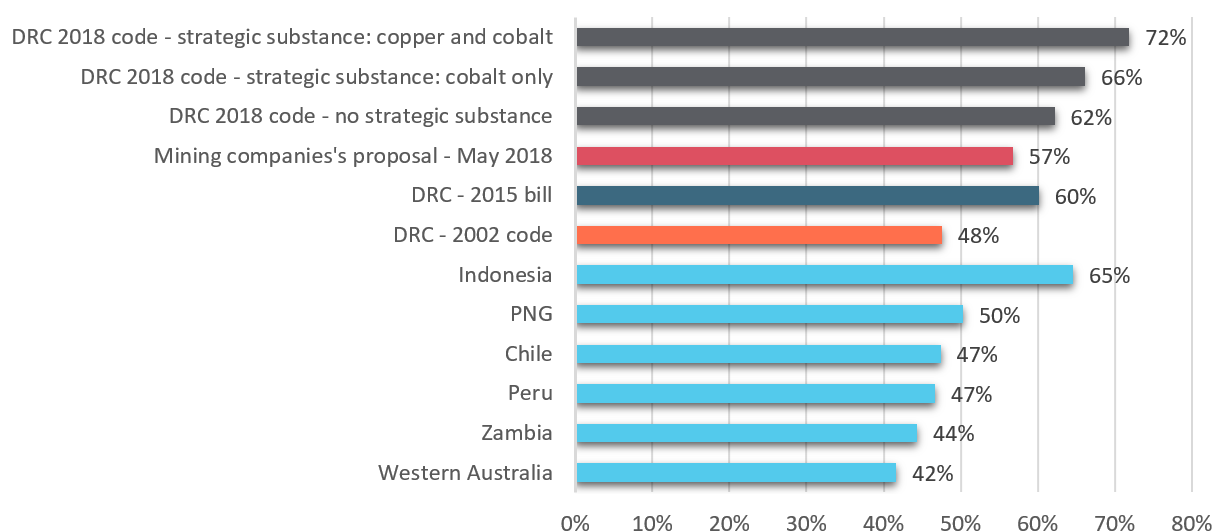

This year, we have updated our analysis and fiscal models with the final terms of the mining code as it was actually amended. Our new analysis shows that the DRC’s fiscal regime has been significantly altered. As the figure below illustrates, it is now much more onerous than fiscal regimes in comparable mining jurisdictions.

Average effective tax rate* from a cobalt/copper project based on the Ruashi mining project  * based on a 10% discount rate, assuming price and cobalt prices trigger the superprofit tax.

* based on a 10% discount rate, assuming price and cobalt prices trigger the superprofit tax.

Source: NRGI, fiscal models

Our new report, which contains details of our analyses, is now available (in French). It should be read jointly with our initial report on the DRC’s mining code reform, the mining code itself and its regulations. All quantitative analyses are based on Excel-built fiscal models updated and published on www.resourcedata.org. Our four main conclusions are:

- The new mining code aims to increase the economic and tax benefits to the country. It includes new taxes and provisions to simplify tax bases and more effectively share some revenue with local governments.

- However, the total economic impact of the new fiscal regime on investors is too great, especially after taking account of the large number of de facto taxes that are collected outside the strict legal scope of the mining code, as well as the mandatory payments to state-owned companies. This could limit the development of the most important sector of Congo’s economy by discouraging investment.

- The government did not adequately consult when it resumed the mining code review process in 2017. The new law contains much tougher provisions than the previous bill, including the immediate application of the code to all mining projects, without transitory measures, despite previous commitments to legal stabilization. By doing so, the government has planted the seeds of a more conflictual relationship with the industry. Several companies have threatened costly arbitration proceedings. Part of the blame falls on companies themselves. They chose to lobby aggressively against the 2015 bill and pushed the government into more radical positions. Companies only offered credible alternatives to the 2002 fiscal regime after the opportunity for reaching consensus had passed.

- Because of the weight and the complexity of the new fiscal regime, the number of payments in addition to the mining code’s taxes, and the limited capacity of the country’s tax authority, implementation of the law will be a challenge. This increases the risk that the prime minister could grant tax incentives, a potential loophole created by the code revisions. This would undermine the universal applicability of the law and create serious governance risks.

In the short term, we recommend that the government prioritize the implementation of the most consensual elements of the new code. The new transparency and local development measures are critically important for Congolese citizens. The government should also attempt to mitigate some of the most negative impacts of the new law. Clarifying the definition of “strategic minerals” and considering a transition period in the implementation of the new fiscal regime would help. We measured the impact of the 10 percent royalty rate that could apply to gold, copper and cobalt if they are designated “strategic minerals.” We found that the impact was much higher if applied to gold and copper than to cobalt, therefore making the designation of only cobalt as a strategic mineral potentially more palatable to investors. In any event, classifying any mineral as strategic should be based on a thorough market analysis.

In the longer term, when the political situation allows for constructive engagement with all stakeholders, we recommend that officials review some of the most problematic elements of the new code. This should be done through a short, efficient and confidence-building process. The government could then consider in particular replacing the new super-profit tax with a more easily implementable tax, such as a variable-rate royalty, and removing the provision of article 220 that allows the prime minister discretion to offer tax incentives and grant exemptions to the code by decree.

A more balanced fiscal regime is needed for the Congolese mining sector to bring the maximum benefits to the country. NRGI remains committed to supporting all stakeholders in pursuing this objective.

Thomas Lassourd is a senior economic analyst at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). Jean-Pierre Okenda is NRGI DRC country manager.