Préserver la base d’imposition en Afrique: étude régionale des défis posés par la détermination des prix de transfert dans le secteur minier

Le présent rapport évalue le développement et la mise en œuvre des règles de contrôle des prix de transfert dans le secteur minier dans différents pays et contextes. Comme l’illustrent les études de cas complétant ce volume, le Ghana, la Guinée, la Sierra Leone, la Tanzanie et la Zambie font face à plusieurs difficultés majeures dans l’application des règles sur les prix de transfert.

Prix de transfert dans le secteur minier guinéen

Read this publication in English here.

La Guinée compte certains des plus précieux et importants gisements de minerai de fer et de bauxite au monde. Avec des réserves estimées à plus de 1,8 milliards de tonnes de minerai de fer, Simandou — dont l’exploitation n’a pas encore démarré — est le plus grand gisement du pays. En 2013, le secteur minier guinéen représentait plus de 28 % des recettes de l’Etat et environ 96 % des recettes d’exportation du pays . Le montant de l’évitement fiscal, en particulier la manipulation des prix de transfert, pratiqué par les entreprises minières en Guinée est difficile à quantifier mais les personnes interrogées s’accordent pour dire qu’il s’agit d’un problème majeur. Des réformes juridiques et administratives complètes doivent être adoptées de toute urgence si la Guinée souhaite lutter contre la manipulation des prix de transfert et préserver la part qui lui revient de la rente tirée de ses ressources minières.

Les prix de transfert correspondent aux prix déterminés dans le cadre de transactions entre des entités juridiques liées appartenant à une même entreprise multinationale. Ces échanges sont considérés comme des « transactions contrôlées », portant par exemple sur l’achat ou la vente de biens ou d’actifs incorporels, la fourniture de services ou de financements, la répartition ou le partage des coûts. Tant que le prix fixé correspond au prix de pleine concurrence, c’est-à-dire à celui d’une transaction similaire entre deux parties indépendantes, aucun problème ne se pose. Toutefois, la détermination des prix de transfert peut prendre un caractère abusif lorsque des parties liées cherchent à fausser le prix pour diminuer le montant global de l’impôt dont elles sont redevables. Dans ce cas, cette pratique est généralement qualifiée de « manipulation du prix de transfert ».

La présente étude de cas examine les obstacles à la mise en œuvre de règles en matière de prix de transfert dans le secteur minier en Guinée. Les conclusions de cette étude forment une série de recommandations proposant des mesures pratiques pour améliorer le contrôle des prix de transfert dans le secteur minier. Ces recommandations peuvent être classées en quatre grandes catégories : cadre juridique des prix de transfert, dispositions administratives, informations sur les prix de transfert, et connaissances et compétences.

Preventing Tax Base Erosion in Africa: A Regional Study of Transfer Pricing Challenges in the Mining Sector

The commodity downturn represents an opportunity to invest in good practices that will help countries break from a legacy of inadequate governance and legal structures, weak enforcement of tax legislation and imprudent revenue management. Making improvements in establishing and enforcing strong governance and fiscal frameworks now to capture resource rents will also pay off when mineral prices rise again.

A critical area of reform is to counter aggressive tax planning and tax evasion. Tax planning, or tax avoidance, is the use of legal methods to minimize the amount of income tax owed by multinational enterprises (MNEs). In the absence of rigorous controls, some MNEs also employ illegal methods to reduce their taxable income by knowingly and illegally misrepresenting their transactions. This is called tax evasion.

The Africa Progress Panel has identified crossborder transactions between related parties as a major threat to the tax base of African countries. One of the principal vectors of losses in these transactions is transfer pricing, which occurs when one company sells a good or service to another related company. Because these transactions are internal, they are not subject to ordinary market pricing and can be used by MNEs to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions.

Many African countries have begun to put legal rules on the taxation of cross-border transactions in place. Most of these rules require taxpayers to price transactions between related parties as if they were taking place between unrelated parties. This “arm’s length principle” is at the core of most global standards on controlling transfer pricing, led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). However, compliance with the letter and the spirit of these rules depends on the administrative capacity of countries to actively enforce legislation. Preliminary results from research by the Institute for Mining for Development Centre suggest that out of 26 countries surveyed in Africa, most do not have the requisite capacity to implement effective transfer pricing rules.

This study assesses the development and implementation of rules to monitor transfer pricing in the mining sector in countries with varied experiences.

NRGI has also published case studies on transfer pricing in Ghana, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zambia. Preventing Tax Base Erosion in Africa: A Regional Study of Transfer Pricing is available in French here.

Listen to a podcast relating to this research:

Direct Social Expenditures: A Monitoring Guide for Civil Society Organizations

This paper provides civil society organizations with different strategies to obtain and analyze detailed information on direct social expenditures (DSE) by companies. It also provides civil society with useful lessons on advancing the transparency agenda in this area.

The World Bank defines corporate social responsibility (CSR) as “companies’ commitment to contribute to sustainable economic development by working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve their quality of life in a way that is beneficial for business and also for development.” Extractive industries engage in CSR because their activities are considered among the most environmentally and socially disruptive and it is critically important for them to secure their “social licenses to operate.”

As part of their CSR extractive companies invest significant amounts of resources to undertake social development programs; in 2001, oil, gas and mining companies disbursed more than $500 million in community development programs. These expenditures can have a large impact on small local economies. When poorly conceived and implemented, they can lead to corruption and undermine government authorities and institutions. In addition, these resources are obtained on the basis of concessions of oil, gas and minerals that belong to citizens. Companies receive fiscal concessions or incentives from the social activities undertaken in the countries where they operate. All these reasons make it imperative that civil society organizations monitor DSE to ensure they are spent effectively.

Companies can employ different mechanisms to disburse DSE. These could be a function of program objectives and other contextual factors. A company might implement different mechanisms in different countries. It could use public or private disbursement channels, or a combination of both. CSOs need to understand these mechanisms and their pros and cons in order to monitor them. The paper studies the experience of two CSOs—Grupo Propuesta Ciudadana (GPC) in Peru and Instituto Brasileiro de Análises Sociais e Econômicas (IBASE) in Brazil—that successfully made extractive companies disclose information on their expenditures and have since monitored and evaluated the impact of these expenditures. Both CSOs created transparency indices and performed social audits to rigorously assess and rank company performance and undertake evidence-based policy advocacy. GPC successfully obtained information from more than 30 companies on $900 billion worth of social expenditures, and IBASE convinced over 300 private companies to disclose their social audits. The paper also explores experiences of countries that have negotiated including direct social expenditures in the disclosure requirements of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Despite progress in companies disclosing relevant data in recent years, transparency of direct social expenditures is more the exception than the norm. Companies should improve their reporting by providing detailed information about the types of projects funded, the objective of such projects, the amounts disbursed, and the persons responsible for allocating these resources. Contracts that include social expenditure obligations should be available for public consumption.

Five Steps to Disclosing Contracts and Licenses in EITI

Disclosing contracts and licenses is one of the most important steps that EITI implementing countries can take to promote more effective management of their extractive resources. Contract transparency promotes constructive relationships between citizens, companies and governments, which can reduce conflict and promote stability in the sector. It helps set realistic expectations about the terms of and timelines for extraction, which facilitates accurate government revenue collection and forecasting. The disclosure of contracts also provides enhanced opportunities for stakeholders to monitor adherence to obligations, which encourages all parties to act responsibly in project implementation.

Contract/license disclosure also enhances the utility of other EITI disclosures by providing context that facilitates the analysis and understanding of revenue flows and other data. For example, Section 4.1(e) of the EITI Standard requires the disclosure and, where possible, reconciliation of material social expenditures that are mandated by law or contract. Without contract disclosure, it is difficult to determine whether contractual social payment obligations even exist, let alone accurately collect and reconcile information on them.

The note begins by looking at how an MSG can start discussing contract and license disclosure, followed by how countries can approach defining the scope of disclosure. Next, we cover mechanisms for assembling and verifying documents and establishing public access to this information. Finally, the note outlines options for maximizing public education and outreach. Throughout the note, we base the discussion on lessons learned from the experiences of the growing number of countries that publish their extractive industry contracts and licenses.

Getting a Better Deal from the Extractive Sector

by Raja Kaul and Antoine Heuty with Alvina Norma

This comprehensive report from Revenue Watch Institute demonstrates the need for more equitable terms in natural resource contracts and the pivotal role that the contract process can play in economic recovery and development.

In 2006, as part of its wider reconstruction effort, the government of Liberia conducted a review and renegotiation of its contracts with the Firestone rubber company and the ArcelorMittal steel company. The resulting amended contracts offered Liberia significant gains, in areas from taxes and corporate governance rules to environmental and social issues such as housing and education.

The amended contracts were embraced not only by Liberia's legislature and general public, but also by Firestone and ArcelorMittal, the latter increasing its investment in Liberia from $1.0 to $1.5 billion. The successful negotiations have also caught the attention of other African governments seeking to ensure that their countries maximize value from natural resource concessions.

Prepared for the Office of the President of Liberia by RWI senior economist Antoine Heuty and Raja Kaul, who was closely involved with Liberia Firestone and ArcelorMittal negotiations, the report includes forewords by President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of the Republic of Liberia and Open Society Institute chairman George Soros.

Table of Contents

Foreword by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, President, Republic of Liberia

Foreword by George Soros, Chairman, Open Society Institute

List of Charts and Tables

List of Acronyms

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Background

Chapter 3: The ArcelorMittal Negotiations

Chapter 4: The Firestone Negotiations

Chapter 5: The ArcelorMittal and Firestone Negotiations: Analysis and Recommendations

Chapter 6: Increasing the Transparency of Concession Negotiations

Chapter 7: Contrasting the Fast Track Negotiations to Other Government Negotiating Practices

Chapter 8: Concession Agreement Monitoring and Compliance

Chapter 9: Conclusion

Appendicies

Endnotes

Nigeria: An Uphill Struggle

Oil Wealth and the Push for Transparency in the Niger Delta

Since 2008, the Revenue Watch Institute (RWI) has been engaged in Nigeria, mostly focusing on increasing transparency and accountability of oil revenues and spending in the country's Bayelsa State, a poor, underdeveloped region rife with social, political and geographical challenges. Bayelsa was the site of Nigeria’s first oil discovery in 1956, and because Nigeria’s constitution requires that all states receive a share of the nation’s oil revenues, Bayelsa has brought in over $2.6 billion dollars since 1999. With careful, accountable and transparent management of its share, the state has a real opportunity to grow and spur development across the Niger Delta.

RWI supported the Bayelsa Expenditure and Income Transparency Initiative (BEITI), a multi-stakeholder initiative that brings together representatives of government, civil society organizations and the private sector to track revenue and expenditure at the state and local government levels. The project also supported civil society organizations to push for increased budget transparency and advocate for better management of oil and gas revenues.

The project has not been an easy one, and its impact remains to be seen. While civil society’s understanding of public financial management systems and ability to analyze and critique government planning and budgeting processes has increased, this awareness has not yet translated into improved transparency and accountability of resource revenues or increased government capacity and performance. Nevertheless, the attempt to develop and institutionalize the initiative has produced lessons critical to replication efforts elsewhere in the country as well as abroad.

This subnational case study explores RWI's work in Bayelsa State and lessons for improving resource management at the local level.

Enforcing the Rules

In many countries rich in minerals, mining deals between industry and government have failed to deliver the benefits citizens expect—not only because of bad contracts but also because governments and civil society fail to effectively monitor and enforce company compliance with the terms of good contracts.

Recent years have brought significant improvements in industry and government transparency, national mining laws and contracts, but monitoring remains the only way to determine whether the deals struck with companies reflect what is being implemented on the ground. Many developing countries with weak regulatory systems lack the capacity or political will to ensure that company obligations are enforced. The result can be losses of billions of dollars to tax evasion and fraud, and harm to workers, the environment and social peace.

Enforcing the Rules: Government and Citizen Oversight of Mining, by Erin Smith with Peter Rosenblum, examines the gaps in effective monitoring of mining obligations, identifies good practices and proposes practical avenues for improvement.

Table of Contents

Cover & Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: Challenges Undermining Monitoring and Enforcement

Chapter 3: Areas of Good Practice

Chapter 4: Conclusion and Recommendations

Appendix 1: Civil Society Monitoring Toolkit

Appendix 2: Mining Company Obligations

Appendix 3: Where to Get Information on Mining Company Operations

Bibliography

Reforming National Oil Companies: Nine Recommendations

Some national oil companies (NOCs) have contributed heavily to successful efforts to harness benefits from the oil sector and drive broader national development. In other cases, however, NOCs have become inefficient managers of national resources, obstacles to private investment, drains on public coffers, or sources of patronage and corruption. As such, NOC reform—incremental in some cases, fundamental in others—lies at or near the top of the policy agendas of many oil-rich countries.

Building on existing literature, we surveyed 12 NOCs from diverse geographical and operational contexts to distill practical steps that policy-makers can take to make their countries' NOCs more effective and more accountable—to governments and to citizens. Our recommendations can be seen in both the executive summary and the full report.

The report's recommendations are based on the experiences of the following national oil companies:

- GNPC (Ghana)

- KMG (Kazakhstan)

- Petronas (Malaysia)

- Petrobras (Brazil)

- Saudi Aramco (Saudi Arabia)

- Sonangol (Angola)

- NIOC (Iran)

- NNPC (Nigeria)

- Pemex (Mexico)

- Statoil (Norway)

- PetroVietnam (Vietnam)

- SNH (Cameroon)

The nine recommendations for companies and the authorities who oversee them— described in detail in the report—are:

| Recommendation | Core features | |

| Defining and financing a commercial mandate |

1. Carefully define commercial and non-commercial roles. Limit non-commercial activities where sophisticated or expensive commercial activities heighten the risk and cost of conflicts of interest. |

|

|

2. Develop a workable revenue retention model. |

|

|

|

3. Procure external financing by listing some NOC shares on public stock exchanges or issuing external debt where appropriate. |

|

|

| Limiting political interference in technical decisions |

4. Define clear structures and roles for state shareholders. |

|

|

5. Empower professional, independent boards. |

|

|

|

6. Invest in NOC staff integrity and capacity. |

|

|

| Ensuring transparency and oversight |

7. Maximize public reporting of key data. |

|

|

8. Secure independent financial audits, and publish them. |

|

|

|

9. Choose an effective level of legislative oversight. |

|

|

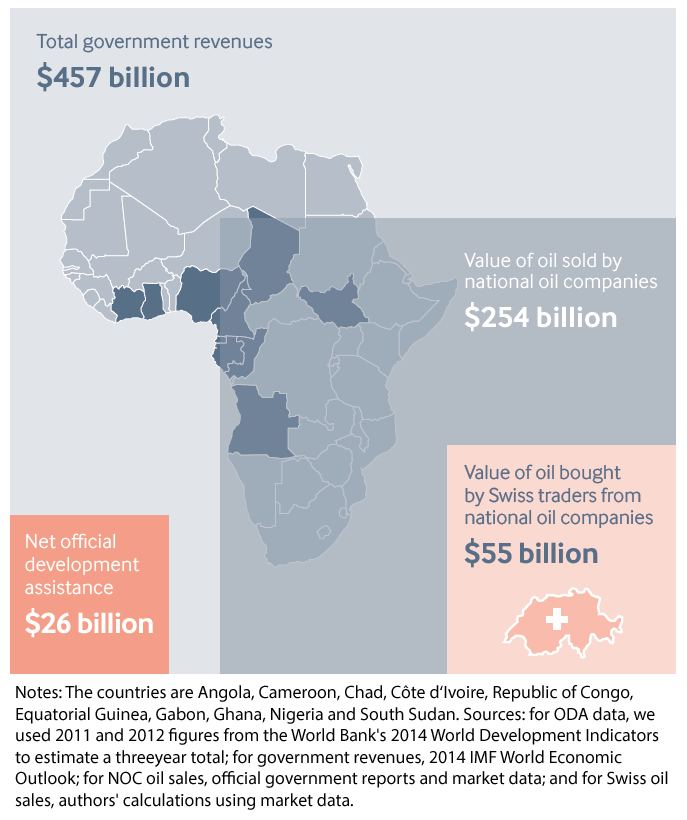

Big Spenders: Swiss Trading Companies, African Oil and the Risks of Opacity

The sale of crude oil by governments and their national oil companies (NOCs) is one of the least scrutinized aspects of oil sector governance. This report is the first detailed examination of those sales, and focuses on the top ten oil exporting countries in sub-Saharan Africa. From 2011 to 2013, the governments of these countries sold over 2.3 billion barrels of oil. These sales, worth more than $250 billion, equal a staggering 56 percent of their combined government revenues.